One of the things being promoted by various Christian is the idea of Christian integralism, the notion that everything in the world should find itself subsumed into a Christian state, a state where Christian moral principles alone serve as the foundation of for its legal system. Such integralists also think that if people are unwilling to enter in and follow such a state, they can and should be forced to do so. Integralists deny the pluralism promoted by religious, as well as, political liberty, and in doing so, undermine the kind of freedom traditionally promoted by the Christian tradition. They want to reduce everything to their own ideological reduction of the Christian faith, and then, embracing an authoritarian take on society, force everyone to follow their reductionist view of the common good. Different integralists might have different moral visions, and some might be more authoritarian than others, but they all think that their own ideology must, in some fashion or another, be promoted by the state and enforced by the rule of law. Christian integralists go beyond what is contained in or represented by the Christian tradition, for if they looked at what Scripture suggested, they would see that even God did not enforce all possible moral positions through the use of positive law. If and when integralists want to make as many positive laws as possible to enforce their own moral conclusions, they establish a legalistic state, which, by the nature of such legalism, undermines the moral freedom God intends us to have. And, though such legalists think the way to make people do good is to create as many laws to enforce their moral conclusions, in reality, all they do is make people rebel, leading them to go against the expectations being placed upon them (as, for example, the history of Prohibition in the United States demonstrates).

Integralism promotes an erroneous, indeed, simplistic, approach to the world; it takes some elements of the truth, and reifies them, exaggerating them and their importance by removing them from the holistic truth; as happens with those who exaggerate some elements of the truth at the expense of others, they end up undermining the fullness of the truth themselves. Because they can, and often, point to a few truths, they act as if anyone who disagrees with their approach to the truth as disagreeing with those truths which they hold. They try to make those basic truths to be the central issue, when in general, they are not, and often, are not things in dispute. That is, in order to defend their unbalanced approach to the truth, they project upon their critics a position their critics do not hold, and then consistently debate that red herring instead of dealing with the real issues at hand.

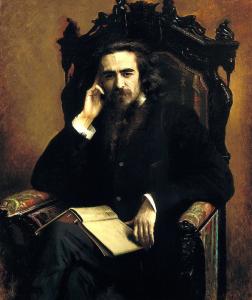

Vladimir Solovyov shared many inclinations with the integralists. He believed and hoped that the world would be coming together as one, into a “Free Theocracy.” He thought this would mean that the world would come together under one spiritual authority (under the Pope), and that it would eventually come together under one secular authority (the “Tsar”). He also saw that the religious and secular authorities would exist in their own sphere, indicating that they should not be subsumed into or morphed into one ultimate sphere, the religious sphere, for that would reduce unity into mere absorption of all things into one instead of realizing the interdependent unity of all things which would preserve the identity of all things in that unity. While many, looking back, could question his own notion of his “Free Theocracy,” nonetheless, it is clear, he was trying to deal with and confront the problems which lay behind the formulation of Christian integralism. He believed the real issue was that of freedom. Unlike Christian integralism, he said that the integral unity of all things should come about on a voluntary basis. Any system which removes such liberty, he explained, follows an un-Christian approach, and indeed, when promoted by Christians, demonstrates a corruption of the Christian faith. He agreed that Christians should engage the world, to share with it grace, to help those in the world come in contact with God so that they can be elevated. But, Soloyvov said, that must all be done in and through the promotion of personal freedom. It is important for Christians to act as servants, helping people embrace their freedom, instead of seeking power for themselves and using it to lord it over others:

It is true that man ought to help the salvation of the world and in leading it to a practical submission to the divine principle, but it is not true that with that object he ought to try to lord it over his fellows. If he wants power, not indeed for himself but in the name of God and for the work of God, to be used in accordance with the divine will, then he cannot and must not seek it, he cannot and must not take any steps of his own to obtain it. I believe in God, I want his will to be done, I hope for the coming of his kingdom, and to that end I must do whatever I am able to do – but I must look for nothing more, for I do not know the secrets of God’s economy, the ways of his providence or the plans of his wisdom; I do not even know myself properly. [1]

Those who would promote an authoritarian approach to the world, such as we find with those promoting integralism, though they often speak of Christianity and Christian truth, in the end, only take a few elements of that truth while denying the rest. Far from being faithful to the Christian tradition or God, they do not trust in and wait for God, which is why they end up justifying all kinds of evil in order to promote the social order they want in the world. Solovyov, upon seeing this, explained that all they do is push people further away from God:

If, instead of waiting on God, I try myself to attain to power, I shall have to use the means that are usual in the world, beginning with deceit and cunning and ending with violence and murder. Men cannot be led to the kingdom of God by such methods, and it is more than possible that I shall be put further away from it. [2]

History shows this time and time again. Many of those who have used the Christian faith to take hold of a position of authority and act as if they are a great Christian leader have only made things worse, because they used the Christian faith for their own benefit instead of letting its teachings take root in their hearts. This is why so, when we look back in Christian history, we see so many Christians in positions of power end up hurting those they rule over. Though they claim to represent the Christian faith, and often use it to justify their claim to authority, in the end, they did not follow the way of love which authentic Christianity teaches:

Generally speaking, the “best men” in Christian society have hitherto been far from what they ought to have been. In the history of Europe they have often been oppressors of the people and unjustifiably hostile toward civil and religious authority; instead of being leaders of the people and willing servants of state and Church they have too often tried to be masters of everything and everybody. By giving this direction to social activity these “best men” have repudiated their own usefulness and function in the Christian order. They have the most important and most honourable task in the work of building up a free theocracy – and they have also the greatest responsibilities. [3]

For Solovyov, “Free Theocracy,” represents something different from what integralists promote because he did not think that the church and state should be so integrated that their relative distinctions are lost. Rather, just as Christ’s humanity and divinity remain distinct, so the state should have its own distinct place in the world where the church does not interfere (even if he thought the ideal state would take into consideration the highest spiritual truths promoted by the Christian faith): “This does not mean that the Church should interfere in civil affairs, but that the state must rule its activity by the highest considerations and not lose sight of the Kingdom of God.” [4] For Solovyov, Christian principles must be embraced freely, and so the state and the church must not undermine the basic human liberty given to us by God. It is this freedom which we find is lost by the authoritarian approach promoted by modern Christian integralism and its desire to shape the world to fit their legalistic approach to morality (a legalism which runs contrary to sound Christian teaching). Integralism confuses morality with positive law. It undermines the Gospel, for the Gospel tells us it is grace, not the law, which saves us and helps us transcend ourselves, to become better than we are today. Solovyov got to the root of the problem when he wrote:

Everybody knows that the rules of positive law are alone nowhere near enough to enable man to attain perfection: one may never have killed, never have stolen, never have infringed any other law, and yet be desperately far from the kingdom of God. Positive law is not directly concerned with the perfecting of man; its object is to give the greatest possible security to his earthly existence (so far as it serves higher ends), to restrain disorderly man, especially those individuals who do not yet see the true aim of life but without whom this aim cannot be reached. Even the moral law and precepts of the gospel are insufficient for perfection if they are taken in the letter regardless of the spirit; the greatest commandment, the one which includes all the others, the commandment to love, can be misunderstood and wrongly applied – not only can be, but has been and is. [5]

Integralism subverts the order of nature and grace, of law and grace. It confuses what should be distinct. It uses pseudo-arguments, pseudo-intellectual, rationales to do so, by telling us that if something is good, the law must enforce that good, even as the law should be used to prohibit any and all violations of the good. Certainly, some evils should be prevented, but those evils are limited, because the power of positive law is limited. It can never save. It can never be the vehicle of salvation. It can never be used to make us do good. Even the great commandment becomes a tool for evil when this is ignored, which is how and why, in history, many people justify torture and other evils by claiming they are acting out of love. They say such extreme measures are needed as they will help make someone change their ways and be saved. This consequentialist abuse of love must be rejected. Though it takes elements of Christian teaching and doctrine, it uses them for the sake of power and domination, the kind which Jesus rejected when Satan offered him such power. While Jesus would not bow to Satan to gain power in the world, the spirit of the anti-Christ encourages it, and so those who give in to it, though they often appear to stand in and represent Christ, actually present the world the Satanic antithesis of Christ and all that Christ stood for. For it is evil, not the good, which leads away from freedom:

Evil is never freely chosen. On the contrary, we are involuntarily pulled, drawn, or chase to evil. The very nature of this “attraction” to evil means that in experiencing it we lose our freedom. Only good is chosen freely, for good alone, coinciding in the depths of reality with being, forms the genuine inner ground of our being. [6]

[1] Vladimir Solovyey, God, Man & The Church. The Spiritual Foundations Of Life. Trans. Donald Attwater (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 2016), 27.

[2] Vladimir Solovyey, God, Man & The Church. The Spiritual Foundations Of Life, 27-8.

[3] Vladimir Solovyey, God, Man & The Church. The Spiritual Foundations Of Life, 118.

[4] Vladimir Solovyey, God, Man & The Church. The Spiritual Foundations Of Life, 112.

[5] Vladimir Solovyey, God, Man & The Church. The Spiritual Foundations Of Life,, 119.

[6] S. L. Frank, The Unknowable: An Ontological Introduction To The Philosophy of Religion. Trans. Boris Jakim (Brooklyn, NY: Angelico Press, 2020), 287.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!