Charity, love, is to be given to all. Those in in need, especially if they are in extreme need, should be given as much help as possible. We should not first question who they are, where they come from, what they believe. All those questions might come up later, but they should not come up when we see them in desperate need for aid. “But if any one has the world’s goods and sees his brother in need, yet closes his heart against him, how does God’s love abide in him? Little children, let us not love in word or speech but in deed and in truth. By this we shall know that we are of the truth, and reassure our hearts before him” (1 Jn. 3:17-19 RSV).

Jesus, the God-man, saw the extreme need we had for his help. Despite what we have done, despite closing ourselves off from God, Jesus came into the world to be with us and do all that he could do to help us. God loves us all, no matter what we have done. “But God shows his love for us in that while we were yet sinners Christ died for us” (Rom. 5:8 RSV).

Jesus should be our example. He came to help everyone. He healed people, whether or not they would show him any gratitude afterwards (cf. Lk. 17:11-19). That is what love does. Love has us help our beloved when they are in need without any consideration of receiving anything in return. Jesus consistently pointed this out in his preaching. He told us to love everyone, to do good for everyone, even those who otherwise were hostile to us (cf. Matt. 5:43 – 48). This is why those who would flee the world out of hate for those within it, trying to separate themselves from the world so that they can be only with those who think and act like them, stand in stark contrast to what God showed us to do in the incarnation. For, instead of reinforcing the separation between God and the world due to the sin the world, God became human and entered the word to lift it up from within.

It is extremely important for Christians to understand the practical implications of the incarnation. Theological reflections should not be done merely to offer interesting theological speculations that otherwise do nothing to help us. Curiosity without just purpose should not direct our theological engagement. Theological reflection concerning the incarnation should flow from our realization of what God has done for us; it should answer questions which arise, if those questions get in the way of our faith, but it should not be done for the sake of personal glory or fame. And when we make our answers, we should always keep in mind that the truths which come out of the incarnation have practical implications association with them.

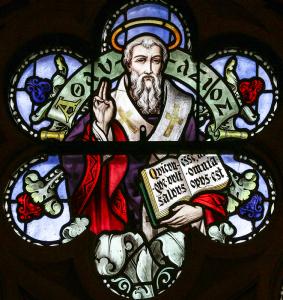

Thus, there is value in engaging the theological sciences, but we must also remember, such reflection is done only after we have come to apprehend some mystery of the faith. Likewise, such apprehensions must remain primary, and our theological reflection should serve that apprehension instead of undermine it and make it seem insignificant. The reality of the incarnation, the work of the incarnation, and the message of the incarnation should not be forgotten. St. Athanasius understood this. While he could and would write much to defend Nicene orthodoxy, he understood Nicene orthodoxy helped serve the greater reality of the incarnation (a reality which transcends our theological reflection), as well as the implications of the incarnation on our lives (such as found in his discussions of theosis). Our interest in St. Athanasius should not be only in relation to his dogmatic disputes, but also what he explained as to how we should live as a consequence of the incarnation. That is, we should not ignore what St. Athanasius taught and did beyond what is found in his dogmatic writings. When we look, for example, at what Egyptian monks remembered from St. Athanasius’ teaching, it is much more practical. He reminded them that the incarnation teaches us that we should engage the world in and with love. This can be found in what the Egyptian monk Paphnutius related in his Histories of the Monks of Upper Egypt. In it, we find the example of a monastic priest, Mark, who came to St. Athanasius, asking what he should do when pagan Nubians asked him for help:

When the archbishop had finished speaking with us, Mark the priest said, ‘There is one thing which is a stumbling block for me, and I would like to speak to you about it, my holy father.’ The archbishop said, ‘Go ahead.’ Mark said, “To the east of us and to the southwest of our said there are pagans called the Nubians. They are very poor and they regularly call to us, “Give us bread.” I am moved to say “No” to them because they are pagans [and do not worship] God.’ [1]

St Athanasius answered the question by indicating various Scriptural texts which showed God was at work with people throughout the world. He said that God did not and would not abandon anyone, even if they, in some sense or another, abandoned God. God is the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, but not just them: God is the God of everyone. There is but one God who looks to and engages the world with love. [2] God tells us to knock, and we shall receive. We should follow that example, and so we should help those who come to us for help which we can give them. St. Athanasius, indeed, read the story of the Canaanite woman (St. Photina) as a way to show how God would have us give to all who should ask for our help:

The archbishop said to him: ‘Can it be that you have been ignorant of these things before now? Have you not read in the Gospels that our Saviour said to the Canaanite woman? He said, “It is not good to take the children’s bread and theow it to the dogs”. And she responded, saying, “Yes, lord, but the dogs also eat the crumbs that fall from their masters’ table”. Observe how our Saviour commended her answer. He said to her, “Woman, great is your faith. May it be done for you as you desire.” And her daughter was healed from that time on because of what she had said.’ [3]

Athanasius, then, said it is better to do what is right, that is, to engage justice, than not to do so. He also explained that it is far better to do so with the right motivation, that is love, and so to do so freely than to be forced to do what is right through some external force or motivation (such as by rule of law). But he didn’t deny the need for such force, when we will not willingly do what justice expects of us. Thus, he told Mark that it would be wrong to neglect helping people just because they were pagans:

Now then, my son Mary, I have told you these things on account of the pagans you told me about. It is better for you to force yourself to do something for love’s sake, than to be forced without love in your heart, for love covers a multitude of sins. As regards these pagans, they will come to believe in God after awhile, and therefore, I have said all these things to you. I find you to be like a kernel of seed in its shell, as Isaiah says, Do not destroy the one who has the Lord’s blessing in him. [4]

Athanasius did not deny, therefore, that pressure could be used to make sure people engage justice, and so, to help those in need, but he said it is better to do so out of love than force, showing charity is indeed greater than justice. We should not pit charity against justice as a way to undermine the expectations of justice. The perfect should not be the enemy of the good. It is better to promote the common good, and help those in need, than it is to make it all voluntary, when, if everything were made voluntary, the common good would be destroyed and many people would needlessly suffer grave injustices (such as not receiving basic human rights). Those, then, who would try to close themselves off to the world, who would deny basic necessities to those they think are evil sinners, do so, not only contrary to the dictates of justice, but contrary to the expectations of love. When they try to pit charity against justice as an excuse to ignore such needs, they only show that they have no love and in them. Then, those who are in positions of authority are right to enforce justice, making sure the common good, and the basic needs of all, are supported.

Athanasius, in his practical wisdom, was remembered by monks for the insight which follows from and complements his dogmatic understanding of the incarnation. It is an insight which should not be forgotten. Instead, it should be highlighted and connected with the rest of his Christological reflections. Christians need to learn from that insight, for when they look to the world and see people in need, they need to embrace those people, helping them instead of finding any and every excuse to ignore them. Athanasius understood such an excuse ran contrary to the incarnation itself. For, it is clear, if God acted with the same ideology as those who separate themselves from the world as a way to keep themselves untainted from the evil they believe is in it, no one would be saved.

[1] Paphnutius, “Histories of the Monks of Upper Egypt” in Histories of the Monks of Upper Egypt & The Life of Onnophrius. Trans. Tim Vivian (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1993), 101.

[2] cf. Paphnutius, “Histories of the Monks of Upper Egypt,” 101-2.

[3] Paphnutius, “Histories of the Monks of Upper Egypt,” 102.

[4] Paphnutius, “Histories of the Monks of Upper Egypt,”, 104.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!