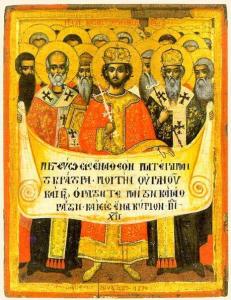

Due to the importance of the council, and the limited historical records we have coming out of it, the Council of Nicea has become the stuff of legends. Stories have been told about it which have little to no empirical history to back them up. Some of them, like the story told about St. Nicholas punching Arius, have every indication of being pure fabrication. While it is possible St. Nicholas was at the council, as we do not have a full and accurate list of all its participants, the story falters when it has Nicholas go against his own known character, that is, of a kind, generous man who looked after those in need. Another legend, one which has some possibility of being based upon an actual event, concerns an intervention made by the monk-confessor–bishop Paphnutius:

The bishops assembled at Nicea in those days were of a mind to introduce a new law that sacred ministers (meaning the bishops, priests, deacons, and sub-deacons) should not sleep with the wives whom they had married when they were still laymen. Rising in the midst of the assembly of bishops, Paphnutius vociferously spoke against the imposition of a heavy yoke on the sacred ministers, saying that “Marriage is honourable”, as it is written [Heb 13:14], and that they should not damage the church by excessive severity, for not everybody was capable of tolerating the rigour of impassibility and perhaps they would not be protected by chastity (he called relations with one’s legitimate wife chastity). It would be sufficient [he argued] for an [unmarried] person presenting himself for ordination not to contract a marriage in the future (in accordance with the ancient tradition of the church) without [a married one] divorcing the wife whom he had already once married when he was formerly a layman. He said this even though he had no personal experience with marriage, or, to speak plainly, of a woman, for he had been raised in a monastery from infancy and he was famous for his chastity. All the bishops were won over to Paphnutius’ arguments; they stopped discussing this topic, leaving it to the judgment of those who wished to distance themselves from marriage. [1]

This story, though placed in the anonymous collection of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, comes from the Church History of Socrates Scholasticus, written in the early 5th century. The lack of earlier references to this event, let alone to Paphnutius, have led some scholars to reject not only the event, but the existence of Paphnutius. Others believe our sources for them are sufficiently close to the time of Nicea that the story could be based upon an actual event. Whether or not it was historically true, it became an important legend, one which have been used by those who support married clergy to show that the Council of Nicea concluded that not only could married clergy continue to be with their spouses, they did not have to abstain from sexual relations. Indeed, the story indicates sexual relations are honorable, and should not be seen as defiling the couple (an important point, considering the way many have since treated sexuality).

Paphnutius is said to have been a disciple of St. Antony who had been severely tortured under emperor Maximinus, whereupon he lost sight in his right eye. Miracles were said to happen around him, drawing the attention of Constantine, which is one of the reasons why he was believed to have been called to be at Nicea. It is interesting that it is someone with such a stature who is invoked to not only defend married clergy, but sexuality as well. It took a celibate to point out the good of marriage, a good which was more than an aid for those who do not have the strength to persevere in celibacy. This legend became the story the East would use to preserve the use married clergy even if Eastern theological reflections did not always go as far as Paphnutius in defending the sanctity of the marriage bed; indeed, the East did give way to some of the pressures coming from the West, which is why bishops eventually were expected to be chosen from those who were not married. Yet, the legacy of this story is such that it made sure that married clergy would continue to exist and that they could have a healthy sexual life. While this is a legendary story, even if it might actually be based upon something which happened at Nicea, it was clearly remembered in a way which does not appear probable; that is, there were likely more than Paphnutius who supposed the continued use of married clergy in the church, and so he would not have been the lone voice having to convince everyone else at the council to agree with his intervention. He could not have been the lone voice for the tradition, for if he were, then his intervention would have been rejected.

What we see coming from Nicea, that is, legendary stories such as those of Nicholas and of Paphnutius, indicates the way the council became important later in Christian history. Legends were made to support ideological positions. While Nicea was intended to help draw Christians together, to establish a way they could speak in common about the Christian faith, it was not meant to become an inflexible presentation of the Christian faith. It was always open for further development. The fathers of Nicea understood the problem of trying to declare transcendent truths with words. They accepted that there could and would be better presentations. This is why it was not seen as problematic for the Council of Constantinople to edit and rewrite the creed. Nicea was not meant to be used as an excuse to justify hatred and violence, despite the way some like to use the legend of Nicholas to take on and fight “heretics” or anyone they don’t like. It was about drawing Christians together, recognizing that there will be some things which they need to agree in common, even if there can be and will be differences in their engagement of the faith. To be sure, this does not mean Nicea promoted anarchy, that anyone who claimed to be Christian should be accepted as such; it set a few norms, such as the teaching of the divinity of Christ, norms which it used to make sure the faith passed down to it could be passed down to later generations.

Nicea, and its fathers, became a thing of legend. We must remember it was not always seen as important as it would become. Many orthodox believers, like St. Cyril of Jerusalem, had problems with the creed. They had had to have proof that the term homoousious could have an orthodox interpretation They had to see how it was being understood by its adherents. Once they understood the intention behind its use, they accepted the creed. One of the lessons we can learn from this is that we should not be so concerned with the terms we use to explain the faith. We should know that any term we use will fail to present the fullness of the mystery of the Christian faith. We must recognize that people will interpret the terms we use differently, and so, they might not accept our terms, but in the end, they will mean the same thing we do with the terms they use. Thus, we should be concerned with the intention and meaning behind the words we use to express the faith than the terms themselves. Terms can and will have different meaning for different people. We must try to understand the intention others have with their words, accepting the most charitable possible interpretation possible instead of forcing the worst possible interpretation upon them. If this lesson had not been forgotten, it is likely the controversy surrounding the filioque would never have developed.For what the fathers following Nicea learned is that even with their differences, differences which often get overlooked in the legends about Nicea, they could come together and find a way to express their common faith, accepting that there would be many ways, many different terms,to do so. This, and not the legends which developed afterward, is what we should learn from Nicea. We must try to avoid needless disputes with others. We certainly should stop and think about what we are saying, making sure we are not being polemical when there is no reason for us to be so. We should realize that there are a wide variety of expressions which can point to one and the same transcendent truth, so that we should not fight each other over which we think is best if we can find that they, in the end, are talking about the same thing as we are with different words. And, certainly, we should not be like how Nicholas is presented in his legend, for in it, all he did is have Arius become defensive and double down in his theological error, which, in the end, runs contrary to Christian charity, a charity which looks to find a way to overcome rifts by bringing those in error to a new, greater understanding of the truth.

[1] John Wortley, trans., The Anonymous Sayings Of The Desert Fathers: A Select Edition And Complete English Translation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 263-5 [N410 BHG 1483n].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.