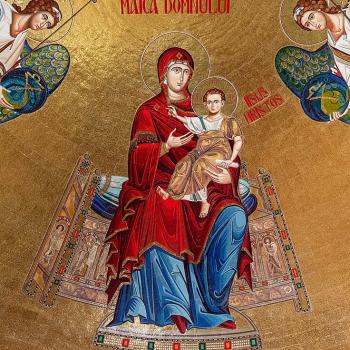

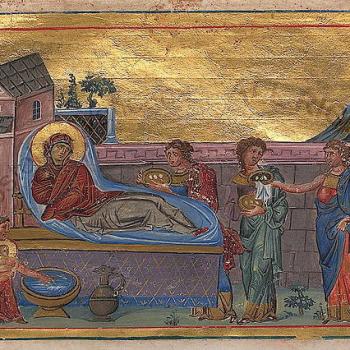

Both Christ and his mother, Mary, are known for their compassion, for the way they love humanity. Both of them are concerned with the salvation of our souls but not to the exclusion of our bodies and the suffering we experience in and with them. They know the sorrows of life because they likewise experienced them, each in their own way. For example, Jesus wept when Lazarus died; his sorrow was real, as his friendship and love for Lazarus was real. Mary, who was predicted to suffer when she brought Jesus to the temple, suffered with Christ when he was tortured, when he was put up on the cross, and when he died. Both suffered various other hardships in the world, such as when Mary was at first questioned by Joseph for her pregnancy, or when, after Jesus was born, the holy family had to flee their homeland and become refugees in Egypt (where they were often treated with hostility and contempt by the Egyptian people). They also knew happiness and joy; suffering and joy are not exclusive to each other – indeed, those with great sorrow often try to find the little things in life to help them find some relief, some little joy in the midst of all their pain. And certainly, due to their holiness, to their purity, both Jesus and Mary have at their core a happiness which could not be taken away from them. They knew sorrow, but they knew a happiness and joy behind and beyond that sorrow; in their sorrows, they find themselves in solidarity with all who sorrow, all who suffer, especially those who suffer from the injustices of the world, even as they can, and often, give comfort and even a little joy to all those who sorrow.

Ivone Gebara and Maria Clara Bingemer present to us a way in which the assumption of Mary shows us what we will all experience in the resurrection to come. It follows from Jesus’ resurrection from the dead, with Mary’s assumption showing us, as a representation of us and all humanity, that we will all have our own share in the resurrection to come. Finally, as Jesus’ resurrection shows us the triumph of God’s love over sin, and the injustices which flow from such sin, so Mary’s assumption similarly shows us that God’s victory over sin and all the injustices it creates does not end with Jesus but continues in and with all of us:

Mary’s assumption, however, is intimately connected to Jesus’ resurrection. Both events of faith are about the same mystery: the triumph of God’s justice over human injustice, the victory of grace over sin. Just was proclaiming the resurrection of Jesus means continuing to announce his passion which continues in those who are crucified and suffer injustice in this world, by analogy, believing in Mary’s assumption means proclaiming that the woman who gave birth in a stable among animals, whose heart was pierced with a sword of sorrow, who shared in her son’s poverty, humiliation, persecution, and violent death, who stood at the foot of the cross, the mother of the condemned, has been exalted. Just as the crucified one is the risen one (see Acts 2:22-4), so the sorrowing one is the one assumed into heaven, the one in glory. She who, while a disciple herself, shared persecution, fear, and anxiety with other disciples in the early years of the church, is the same one who, after a death that was certainly humble and anonymous, was raised to heaven. [1]

Mary was taken to heaven and received her share of the resurrection of the dead; now, in heaven, experiencing the glory of the resurrection, and the deification which comes with it, she continues to comfort those in need. She did not lose her solidarity with those who sorrow, but rather, she embraces it even more. This is why she is known, throughout Christian history, as one who comforts and and brings joy to those who sorrow:

The assumption is the glorious culmination of the mystery of God’s preference for the poor, small, and unprotected in this world, so as to make God’s presence and glory shine there.[2]

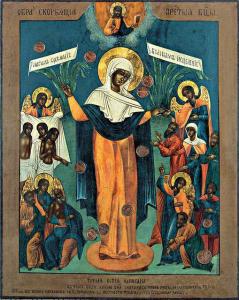

Mary is the joy of all who sorrows, as indicated by several miraculous icons associated with her that bear that name – the joy of all who sorrow. They show Mary being flanked by the poor, the sick, those who are in need of help, with the implication being she will give it out of her great love for them. She has love for all of us, but especially, the least among us, those who have no one else to care for them. One of the icons bearing the name the joy of all who sorrw was in a chapel in St. Petersburg, which, on July 23, 1888, lightning struck, leaving only the icons and 12 coins from the poor box behind. Mysteriously, the coins somehow becoming attached to and a part of the icon itself. After news of what happened became known, believers made a pilgrimage to see the icon, considered it miraculous, with many of them having various maladies which were said to have been cured. Now, there are icons being made in the image of the miraculous icon of 1888, icons which now depict the coins found on the original, coins which have been given up and left behind while the poor, the suffering, the sorrowful, receive help and joy from Mary. She gives to them her love as she would with her son because in the poor, in those who are needy, in those who are full of sorrow, we encounter Christ her son:

Since Christ has identified Himself wholly with every man, in every one of his sad and most sorrowful states, the person who “does it to the least of his brethren” does it to Christ Himself—not “as if” to Christ, but to Christ in reality, for Christ is most truly within every man, and every man is the bearer of Christ, the “image of the invisible God” (Col 1.15).[3]

If we see Mary as a representative of humanity, of the way humanity can be and will be lifted up with Jesus and glorified in the eschatological kingdom of God, we should learn from her that those in heaven will continue to look after and care for the least among us. They will bring joy to those who sorrow. They will give love to those in need instead of looking down upon them. They have not cut themselves off from the rest of humanity, but rather, they have joined and connected themselves even more to every human person, thanks to that love. And if she represents what we should be like, then, we should, in our lives, likewise seek to bring joy to those who sorrow, helping those in need instead of adding to their sorrows.

[1] Ivone Gebara and Maria Clara Bingemer, Mary Mother of God, Mother of the Poor. Trans. Phillip Berryman (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1989), 120.

[2] Ivone Gebara and Maria Clara Bingemer, Mary Mother of God, Mother of the Poor, 120-21.

[3] Thomas Hopko, The Orthodox Faith. Volume 4: Spirituality (Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1981; rev. ed. 2016), 176.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.