Standard Christology describes Jesus as being God and man, one person with two natures. Those natures remains intact, they remain what they are. That is, they are not mixed with each other, creating a third, new nature. Nor does the humanity, in its unity with the greater divine nature, find itself lost and annihilated. The two natures remain distinct and intact.

Theology, however, talks about the “communication of idioms,” communicatio idiomatum, in which, because the two natures are united in the divine person of the Logos (God the Son), we can describe what happens to his humanity in relation to his divinity, and what his divinity does in relation to his humanity. For the person is one and the same. By doing this, we are not confusing the natures, but realize Jesus, the incarnate Logos, is only undivided subject. This is why we can say God eats, not because we are saying the divine nature is eating, but because Jesus, who is God, eats. Likewise, we can talk about the death of God because Jesus died. The divine nature did not die (for it cannot), but the person who is God died because he died in accordance to what happened to his humanity.

Other kinds of unions work the same way. When we talk about the way humanity is called to the divine life, to be united with God, to theosis, we must recognize that such unity does not change human nature nor destroy it. Deified humanity remains human. Likewise, when people are united together as one, such as when we see the whole of humanity are united as one in their human nature, personal distinctions are not eliminated (which is why humanity is called to be one, like God is one, because the one God is tri-personed).

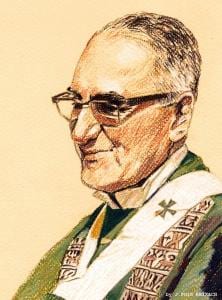

This analysis is important because it helps us to understand not only how we come together as one in the body of Christ as Christians, but how Christians can join themselves together with non-Christians, work with them, be united with them, without losing our Christian character. Christians not only can be involved with politics, they are called to serve the common good through politics. They are able to do so, remaining Christian, without requiring them to identify their political nature as Christian. Their Christian faith will influence their political decisions, but their political decisions must not be confused as if they have to be seen and identified as Christian. Indeed, as St. Oscar Romero wrote, Christians must not identify (and so confuse) what is expected of them politically with what is expected of them from their own particular walk of faith:

This is where the problem arises: faith and politics ought to be united in a Christian who has a political vocation, but they are not to be identified. The church wants both dimensions to be present in the total life of a Christian and has emphasized that faith lived out in isolation from life is not true faith. However, one also has to be aware that the task of the faith and a particular political task cannot be identified. Christians with a political vocation should strive to achieve a synthesis between their Christian faith and their political activity, but without identifying them. Faith ought to inspire political action but not be mistaken for it. [1]

The Christian faith provides its adherents principles which they must uphold, but it does not tell them how those principles are best executed in any particular political reality. We must recognize that secular society must give people freedom, and that freedom requires the possibility that not everyone will follow all the principles which we uphold, let alone execute them in the same way. Each particular society, each particular context, will provide different questions and answers as to how those principles can or should be engaged. Christians must recognize, when they are engaging politics, they must do so, using the very principles of the society they find themselves within, trying to promote justice and the common good in the ways most appropriate to that society. Obviously, if a particular society is being governed in such a way to deny the common good, such as when a tyrant is in power, Christians can and should work to rectify the situation.

Sadly, a problem we find within contemporary political debates is that Christians often do not understand the proper relationship which should be had between the civil state and their religious faith. They must not confuse their Christian identity with their political identity, morphing them together into some new, third category, one which doesn’t fully represent their Christian principles because they assume many secular political attitudes and transform their Christian faith to represent those political ideals. This is the problem underlying integralism, and its error is the same as those who try to confuse the natures of Christ into one. Thus Christianity is politicized, causing scandal as people are told they must hold various ideologies despite those ideologies can be seen to stand against the message of Christ (is this not what we find in those who promote the rich and powerful over the poor and the oppressed?).

Christian politicians must be honest politicians, keeping to their principles, but applying them prudentially. They must not confuse their Christian loyalties to their political loyalties. They must not try to remake the political state in their image of the church, especially when their views of the church are already perverted by their own political ideologies. St. Thomas Aquinas recognized this, which is why he pointed out various sins, even serious ones, should not always be prohibited legally. He understood that legislating morality could not always be enforced, and those who tried to do so, would make things worse instead of better. This is why he believed prostitution should not be outlawed, not because he thought prostitution should continue, but rather, he thought it would be impossible to stop, and it would hurt, instead of help, more people if it were made illegal.

Jesus told us that his kingdom is not of this world, meaning that he did not want us to confuse any political system with his eschatological reign. The kingdom of God is among us. While the eschaton is immanent, it is not only immanent, it is also transcendent. To simply identify any political order with the eschaton is to undermine the eschaton, as the political order is absolutized and confused for being transcendent when it is not. Grace is cut off insofar as the transcendence is cut off, and so what might start as an attempt to realize heaven on earth realizes, instead, a new kind of hell.

Christians, of course, must not deny themselves. They must not deny their faith and its principles. They must bring the grace of the kingdom of God wherever they are at. They can’t do it by force. They must rather be humble about it, following the humility of Christ himself. Likewise, they must realize grace is meant to perfect nature instead of undermining it. It is not to destroy and create something else in its place. This is why Christian politicians can – and will – have principles they believe in and follow which they know cannot be, indeed, must not be politically enforced. They will seek to instill grace in the political system, but, so long as that system seeks after and works for the common good and justice (which is the point of politics), they will do what they can with the grace they have to make that push for justice better, more effective. What they will not do is subvert the secular sphere but trying to make it something it is not, and so confuse the political system with the Christian faith. For if they do, if they try to make what is not meant to be identical, identical, they will find they have given into the temptation to power, the temptation which Jesus rejected when he was in the desert.

[1] St. Oscar Romero, Voice of the Voiceless: The Four Pastoral Letters and Other Statements. Trans. Michael J. Walsh (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2000), 100 [Third Pastoral Letter].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!