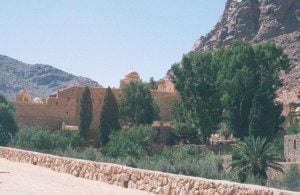

St. John Climacus, one-time abbot of St. Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai, gave us his book, The Ladder of Divine Ascent as a classical representation of monastic discipline and spirituality. While it was written by a monk, for monks, with the intention of helping support the monastic way of life, contained in it are spiritual gems which have not only made the text a classic, but have also made St John Climacus a representative of the penitential way of life during Lent.[1] His text gives expression to his experience, some of which is beneficial, not just for those with a religious vocation, but for all of us as we work out our salvation with fear and trembling.[2]

Our interest here is in the path of prayer described within the Ladder. The height of prayer is found through the path of humility. We might speak a lot to God, ask him for all kinds of things, as we begin our journey toward him, but eventually we find all such things are distractions, hiding ourselves from ourselves and from God. We then empty ourselves of all distractions, that is, we empty ourselves of everything, until we fall before God in total silence, awaiting what he would have to do with us. “But the LORD is in his holy temple; let all the earth keep silence before him” (Hab. 2:20 RSV). Thus, St. John Climacus explained:

Intelligent silence is the mother of prayer, freedom from bondage, custodian of zeal, a guard on our thoughts, a watch on our enemies, a prison of mourning, a friend of tears, a sure recollection of death, a painter of punishment, a concern with judgment, servant of anguish, foe of license, a companion of stillness, the opponent of dogmatism, a growth of knowledge, a hand to shape contemplation, hidden progress, the secret journey upward. For the man who recognizes his sins has taken control of his tongue, while the chatterer has yet to discover himself as he should.[3]

Intelligent silence – not just any silence, but rather, the kind which engages the intellect and uses it to silence our mind from all outside influences, all desires, all thoughts which would distract us from the presence of God in our life. It flows out of humility, because it knows anything we could bring to God would only get in the way of God and so hinder our experience of him. We free ourselves from all forms of dogmatism, that is, of all attempts simplify the truth to use as a way to control other people, and of all attempts to make absolute conventions which cannot and will not meet the truth of God.[4] It is only when we have mastered silence that we find the full fruits of prayer.[5]

This is exactly the experience reported to us by Servant of God, Catherine de Hueck Doherty. Such silence took her to the core of herself, where all things, all thoughts, were removed, so that she entered what she describe as nothingness or nonexistence, experiencing the nothingness which is the foundation of created being. It was there she was able to find God and truly let God make of her entirely as he will, because she had nothing left to get in the way of God’s work in and with her. Grace is most effective when we put nothing in its way and put our will in total cooperation with God’s will. Once Catherine embraced the nothingness in which God was to be found, she was, as it were, recreated. She then found herself emerging out of the nothingness with a close bond to God, and with that bond, she was able to have true prayer with God:

Sartre talks much about moving toward nothingness. But Sartre really has nothing. It’s the end. Christianity move into this “nothingness” and find God. There comes a moment in this movement toward nothingness that seems to be a moment of nonexistence. It appears idiotic, positively idiotic to say such a thing. But it’s true. It’s a moment in which you are nonexistent as far as being a person is concerned. Everything has disappeared. You are not even cognizant that “you are.” You are cognizant only of darkness. Whether you are in depths or heights is unimportant: you are not even cognizant of that. But there is a moment of nonexistence out of which you come. And when you come out, prayer begins.

This moment of nonexistence is short, exceedingly short. It hits you and is gone. But after that, prayer begins. Now it’s a very strange prayer. It’s a prayer that is no prayer, because it takes place in an interiorized passivity. It has no connection with what you are doing – walking, sleeping, whatever. In you now there is a tremendous change. Prayer begins to make sense because now you don’t pray; God prays in you. There is where true liberation enters. [6]

Thus, when we are ready for higher forms of prayer, we begin by entering silence, and this is done in and through a process by which we purify our mind and cleanse it of all thoughts, of all distractions so that it is open and free to be received by God. In such a state, we hold ourselves still, paying careful attention to the work of God in us and listening to all God says to us in that silence, until we find ourselves emerging in ecstasy: “The beginning of prayer is the expulsion of distractions from the very start by a single thought; the middle stage is the concentration on what is being said or thought; its conclusion is rapture in the Lord.”[7]

For that silence is an embracing of who and what we truly are when compared to God: nothing. This nothingness is our foundation; God created us ex nihilo. To know ourselves is to know this nothingness from which we emerge. This nothingness must not be seen as some sort substance, turning nothingness into being, but rather—it is the fundamental lack of being which makes us contingent entities in the realm of becoming – that allows us to be shaped, molded and transformed by God in and through his love.

This silence, this stripping away from ourselves all things which we try to hold as a way to hold ourselves up against God, allows us truly to be humble. In it we hide, as it were, from the world by divesting ourselves from it and all its noise, accepting our fundamental nothingness, so that through it we can be truly ready for God in our open acceptance of who we are, as St. John of the Cross taught: “The humble are those who hide in their own nothingness and know how to abandon themselves to God.”[8] For, once we come to terms with our nothingness, we are free to be molded and shaped by God. We end up having nothing in us to resist the work of God in our soul: “These impediments of contrary attachments and appetites are more opposed and resistant to God than nothingness, for nothingness does not resist.”[9]

We must divest ourselves of all thoughts or beliefs that we have anything to offer God other than our need for him, for without him we are nothing. We need his grace. We need him to show us himself so we know the Truth in and through him. Realizing our fundamental nothingness, we are ready for him and his Truth, while if we hold on to any thoughts constructs of our own as the truth, what we hold to holds God back from us and leads us away from the Truth, as St. Teresa of Avila wrote:

It is because is supreme Truth; and to be humble is to walk in truth, for it is a very deep truth that of ourselves we have nothing good but only misery and nothingness. Whoever does not understand this walks in falsehood. The more anyone understands it the more he pleases the supreme Truth because he is walking in truth.[10]

Such humble silence, moreover, prepares us for the judgment of God. For all that is held on to shall be tried as if by fire. We should mourn for all the falsehood in our lives, for all that we hold to which blocks God from us. This is why we must come, as it were, naked before God. As long as we hold on our thoughts and desires, they shall become the focal point of God’s just judgment against us, as St. John Climacus warned:

When we die, we will not be criticized for having failed to work miracles. We will not be accused of having failed to be theologians or contemplatives. But we will certainly have some explanation to offer to God for not having mourned unceasingly.[11]

We should divest ourselves from all our distractions, all those things we put in our mind and we act upon which get in the way of our humble relationship with God. When we truly embrace our nothingness by putting nothing in ourselves to be judged, there will be nothing which we need to explain to God: our silence will need no explanation; it is but our noise, our useless chatter, every vain word, which shall be judged. Thus, we are told, “Rise from love of the world and love of pleasure. Put care aside, strip your mind, refuse your body. Prayer, after all, is turning away from the world, visible and invisible.”[12] We must strip our mind of all things, even of its attention towards the invisible powers of the world, so that it has nothing in between it and God. This is not easy to do it. Indeed, it is a process which we need to learn, a process by which we slowly find the way to silence ourselves, to remove the noise from our minds – bit by bit. Some, thanks to the grace of God, might be a natural at this, but most of us find it is not something we can do instantly, and indeed, many if not most of us won’t perfect such silence in our lifetime. [13]

It is grace which helps us open ourselves up to God by emptying or divesting from ourselves all that gets in the way of us from God. It is our cooperation with grace which allows us to silence ourselves and enter, as it were, in the stillness of our heart and await God’s loving response. But if we ever fully experience and achieve this silence, this purification our ourselves from ourselves, and truly know ourselves because of it, experiencing the nothingness from which we came, we end up seeing God in that nothingness and then…. return back to the world, refreshed, renewed, capable of engaging the world in a new way. The noise of the world, the noise within our minds, will no longer will be distractions, indeed, will no longer need to be silenced, but they will be experienced in the mode God intended them to be experienced, so that they will no longer need to be avoided: “The start of stillness is the rejection of all noisiness as something that will trouble the depths of the soul. The final point is when one has no longer a fear of noisy disturbances, when one is immune to it.”[14]

Until then, as we meditate and embrace God in meditation, with grace, we can find ourselves progressing towards the silence we need to have, coming closer and closer to that stillness and silence where we find God in nothingness. As we progress, we must fight against the temptations which come after each and every time we open up to God in practice of meditative silence. For we will be given all kinds of fantasies, all kinds of visions of glory, suggesting we turn away from the path of emptiness because there is nothing left for us to learn. We will be tempted to believe we have mastered ourselves, that we are superior because of the progression we have experienced, and suggest to us fanciful thoughts of perfection.[15] “When prayer is over, wait quietly and you will observe how mob of demons, as though challenged by us, will try to attack us after prayer by means of wild fantasies.” [16] We will either fall for them, falling down the ladder of divine ascent, or else, we will, thanks to the grace we have opened up to, see them for what they are, whereupon seeing them we can see through them and use them to help us realize how far we have yet to come and humble ourselves even more, emptying ourselves a little more, the next time we enter the stillness of meditative prayer, until at last, we too have seen ourselves and know ourselves and in that knowledge, in that embrace of our nothingness, see God face to face.

[1] In the Byzantine tradition (Catholic and Orthodox), the Fourth Sunday of the Great Fast commemorates St John Climacus.

[2] Cf. Philip 2:12.

[3] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent. trans. Colm Luibheid and Norman Russell (New York: Paulist Press, 1982), 158-9.

[4] Despite the relationship between the two, we must not confuse dogmatism with the promotion of dogma – proper use of dogma understands the limits of the dogma itself in expressing the truth and sees the dogmas as pointers to the transcendent truth beyond words, while dogmatism is overly literal and enforces the dead letter of the words used, even if it contradicts the meaning and intent of them.

[5] This silence, therefore, requires us to empty ourselves of everything, including, and especially views about ourselves. We are to let ourselves die so as to be found alive in Christ. “And he said to all, “If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it; and whoever loses his life for my sake, he will save it “(Lk. 9:23-4 RSV).

[6] Catherine de Hueck Doherty, Essential Writings. ed. David Meconi, S.J. (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2009), 57.

[7] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 276.

[8] St. John of the Cross, “The Sayings of Light and Love” in The Collected Works of St. John of the Cross. trans. Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D. and Otilio Rodriguez, O.C.D. (Washington, DC: ICS Publications, 1991), 97.

[9] St. John of the Cross, “Ascent of Mount Carmel” in The Collected Works of St. John of the Cross. trans. Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D. and Otilio Rodriguez, O.C.D. (Washington, DC: ICS Publications, 1991), 131.

[10] St. Teresa of Avila, “The Interior Castle,” in The Collected Works of St. Teresa of Avila. Volume Two. trans. Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D. and Otilio Rodrigues, O.C.D. (Washington, DC: ICS Publications, 1980), 420-1.

[11] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 145.

[12] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 277.

[13] And so we will find it continues in our afterlife, if need be, in and through “Purgatory.”

[14] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 262.

[15] The traditional term for this error is prelest, that is, spiritual delusion.

[16] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 197.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook:

A Little Bit of Nothing