While the truth must present itself to us, instead of us trying to establish and create it for ourselves, we can speak of it in various symbolic ways, even as we can and do encounter it through several such symbols. That is, as we grasp after the transcendent and we encounter it, we take back with us the various ways it reveals itself to us, giving us the means by which we can speak of it. In our love for the truth, we speak of it, but in our love for the truth, we always keep in mind the limitations of our speech, indeed, the limitations of the symbolic forms in which we encounter the truth so we do not end up halting our pursuit for the truth with mere representations of the truth. We need the symbols, we need the right symbols, because we seek for and desire the truth, and we need to be able to partake of it in forms which we can understand; but on the other hand, we must consider the limits of such symbols and not become too attached to them. Rather, we must seek out and desire what they represent. They are inherently empty, and it is only in and through the absolute truth filling them with itself do they represent the truth and can be used to speak of the truth. When they are taken in as absolutes, they lose their connection with the truth and so are no longer capable of performing their duty for us. Thus, we must at once affirm the truth revealed through such symbols while recognizing that the symbols are just that, symbols of the truth. Likewise, then, Dionysius wrote in his ninth letter:

While the truth must present itself to us, instead of us trying to establish and create it for ourselves, we can speak of it in various symbolic ways, even as we can and do encounter it through several such symbols. That is, as we grasp after the transcendent and we encounter it, we take back with us the various ways it reveals itself to us, giving us the means by which we can speak of it. In our love for the truth, we speak of it, but in our love for the truth, we always keep in mind the limitations of our speech, indeed, the limitations of the symbolic forms in which we encounter the truth so we do not end up halting our pursuit for the truth with mere representations of the truth. We need the symbols, we need the right symbols, because we seek for and desire the truth, and we need to be able to partake of it in forms which we can understand; but on the other hand, we must consider the limits of such symbols and not become too attached to them. Rather, we must seek out and desire what they represent. They are inherently empty, and it is only in and through the absolute truth filling them with itself do they represent the truth and can be used to speak of the truth. When they are taken in as absolutes, they lose their connection with the truth and so are no longer capable of performing their duty for us. Thus, we must at once affirm the truth revealed through such symbols while recognizing that the symbols are just that, symbols of the truth. Likewise, then, Dionysius wrote in his ninth letter:

Wherefore also, the many discredit the expressions concerning the Divine Mysteries. For, we contemplate them only through the sensible symbols that have grown upon them. We must then strip them, and view them by themselves in their naked purity. For, thus contemplating them, we should reverence a fountain of Life flowing into Itself—-viewing It even standing by Itself, and as a kind of single power, simple, self-moved, and self-worked, not abandoning Itself, but a knowledge surpassing every kind of knowledge, and always contemplating Itself, through Itself. We thought it necessary then, both for him and for others, that we should, as far as possible, unfold the varied forms of the Divine” representations of God in symbols.[1]

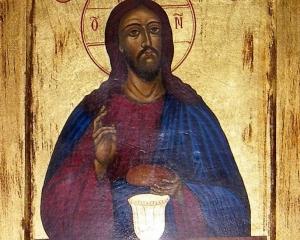

Symbols of the truth can become discredited if and when they apprehended as being something more than symbols, that is, if they are treated as the absolute truth itself instead of a form in which the truth reveals itself to us. We can and will contemplate the truth through symbols; when we speak of the truth, we employ them as the means by which this is to be done, but then we must empty them, realizing that all such symbols are mere symbols, pointers to the truth beyond themselves. They are important, they are invaluable for us, so long as we do not become attached to the form in which the truth is presented, for through them the life and power and grace of the truth flows, giving us a share of the divine life. Through them we can become partakers of the divine nature, with the greatest of these symbols, the sacraments, being mysteries in which the transcendence of the truth is made immanent in a form which we can partake so that through them we can find ourselves in communion with the absolute truth. This is how and why many commentators on Dionysius see a sacramental side to his writings.

In the eucharist, we are to receive the absolute truth in a mysterious form: what appears to be bread and wine is actually the God-man, Jesus Christ. Though we can talk about it in many ways, beyond all such talk lies a mystery, the mystery of communion, whereby we are presented with the absolute truth in a form which we can receive and yet at the same time find it entirely incomprehensible. To receive the eucharist, we must move beyond all intellection, and receive in faith and love the truth which gives itself to us. As we eat, we move beyond all attempts of comprehension, being trained to trust in and receive the truth despite its incomprehensibility. We are moved to love and desire the truth itself and not just expositions of it. Thus, Andrew Louth stated that the reception of the presence of God through the use of symbols while transcending such symbols is a major theme of the Mystical Theology:

According to the Mystical Theology, as one passes beyond symbols and concepts, one comes into the presence of God, a presence which seems like absence because one has passed beyond one’s powers to perceive and understand. [2]

For in the eucharist, we have the presence of God, the presence of the truth, which is what we seek after, though to receive the truth of it, we must look beyond the appearance of bread and wine, the symbols which lie before us, and receive the truth behind those symbols. By receiving Christ in us we are taken in by Christ. We become elevated, therefore, through communion as we experience the presence of God. We receive this truth in symbolic form now, because we cannot comprehend the reality which lies beyond it. Nonetheless, despite the difficulty, we must move beyond the appearances; as we receive communion, we are to look beyond the bread and wine, to strip off from our thoughts all that we think of bread and wine, so to see with spiritual eyes the truth of communion itself, the condescension of truth which lifts us into the truth and lets us dwell with that truth itself. Silencing our thoughts concerning the physical properties associated with bread and wine prepares us for our meeting with God: we must continue to strip away all that is symbolic, all that is conceived by us about the truth, so that we can receive the truth without distraction, without any undue attachment to our thoughts and ideas as to what it is. Then the truth can come pouring into our lives, lifting us up and elevating us; the more we strip away our former attempts to define the truth, the greater insight we can receive, and so, the better we can discuss and explain it to others.

We therefore, must not deny the relative value of symbols. We should appreciate them and use them so long as they have been properly penetrated by the truth. We must not absolutize the symbolic forms given to us and say that we have comprehended the truth through them, but on the other hand, we must not arbitrarily deny them either. We must engage the symbols which have been revealed and employ them as a means, and not ends in themselves. The form which is used to express such a symbol is empty, but becomes full thanks to the superlative goodness of the truth itself. And the greatest of the divine symbols, the greatest of the divine mysteries, the eucharist, shows this best: the truth is with us but not comprehended by us even as Christ is not consumed when we eat of him in communion. Dionysius’ apophatic denials are for the preservation of the truth, not its denial, and why absolute truth must forever be seen as beyond such denials as allowing is to conceive of it in symbolic form.

[IMG=Christ Giving Himself In Communion. Icon owned by and photographed by Henry Karlson]

[1] Dionysius, “Letter Nine” in The Works of Dionysius the Areopigate. Trans. James Parker (London: James Parker and Co,, 1897), 168.

[2] Andrew Louth, Denys the Areopagite (Wilton, CT: Morehouse-Barlow, 1989), 106.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook