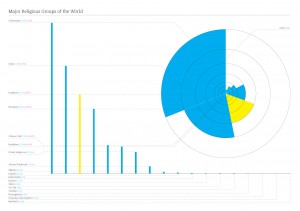

Hinduism the oldest religion that is still practiced today, and between 900 million and 1 billion people around the world belong to this faith. It stands behind Christianity and Islam as the most populous religion. As an aside, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in 2012, Hinduism is in fact outranked by the group of 1.1 billion people who adhere to no faith!

The majority of Hindus, over 950 million of them, live in India, and another 20 million call Nepal their home. Bangladesh and Indonesia are home to 14 million and 4 million Hindus respectively, while Pakistan and Sri Lanka are home to 2.5 million each. Malaysia, the United States of America and the United Arab Emirates each have a Hindu population over 1 million.

Hinduism and Sanatana Dharma

Hinduism stands out among the world’s religions in that it has no individual founder, unlike Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Christianity and Islam. This distinctive quality is only one of many such. Hinduism is also quite multifarious in its core traditions, and is a complex amalgamation of many spiritual processes woven together. This amalgamation was traditionally called Sanatana Dharma, the “Universal Law”. Sanatana Dharma was not a universal law in the sense that there was only one law for all. Rather, it was an individual law for each individual. Every individual was given the freedom to follow whichever path served him in finding ultimate well-being.

The only goal of Sanatana Dharma was to take an individual towards mukti or liberation, the cessation of the repetitive cycle of life and birth. Thus, in Sanatana Dharma, even gods were seen as a “tool”, a possibility that helped us achieve this nirvana. Over a period of a few centuries, beginning around the twelfth century AD with the Islamic invasions of India, the phrase “Sanatana Dharma” was gradually replaced by the word “Hindu”.

There are two possible origins to the word “Hindu”. The first states that the word is a combination of Himalaya and Indu Sagara or the Indian Ocean. The second states that the word was originally coined by the Persians, who lived in today’s Iran, and parts of Iraq and Afghanistan. They applied the moniker to the people who lived to the east of the Sindhu river, which is today known as the Indus. Their mispronunciation of the word Sindhu created the word Hindu.

In later centuries, the Arabs, Turks, Afghans, and Mughals, coming from the Middle East and Central Asia, picked up the word and used it as a label for all people in the sub-continent. Thus, Hindu was a geographical label, and to a certain extent a cultural label, rather than a religious one. With the coming of these Muslim kings, and as they conquered the northern parts of the sub-continent, the word gained currency and was used more often. When the British established their rule from the eighteenth century onwards, they continued the usage, leading to its usage in modern times too. Thus, to look at the Hindu way of life through a religious lens would only serve to confuse a person. This is a common mistake committed by those, especially in the West, encountering the religion. The lack of any specific belief system, the wide range of rituals, the vast array of gods, and the many seemingly contradictory aspects of this mode of life do not carry the hallmark of any religion. To properly understand and imbibe it, one must look at Hinduism not as an “ism” but as a way of life (as the Supreme Court of India famously stated!).

What is Hinduism?

It would quite hard even for a practicing Hindu to state what exactly makes him or her or anyone for that matter a Hindu. It is not unusual for a the husband in a Hindu family to worship one god, the wife another god, the mother a third god, and the father a fourth. Even a lack of belief in god is accepted in the Hindu way of life. The Charvakas and Nastikas who argued that there was no god were a thriving sect in India at one time, and still exist in some form today. This would be quite unthinkable in most other religions, especially the Abrahamic ones. The closest a Western observer could come to this situation is to go back a few thousand years to the Greeks and Romans with their large pantheon of divinities. So it is not any one god that ties Hindus together.

Similarly, the many rituals, customs and philosophical schools coexist beside each other, forming a vibrant ecosystem for human well-being. None of these different schools of thought and doctrines that flourished in the land were labeled as Hindu in ancient times. They were seen as modes for a human being to attain to the ultimate, and individuals were generally free to choose what worked best for them. To each his own! In the past, before the advent of Islam, anyone from the land of the subcontinent was a Hindu, gods, rituals and everything else notwithstanding. With the advent of Islam around the turn of the first millennium AD, perhaps the closest one could come to defining a Hindu would be to say that anyone born in the subcontinent who did not claim adherence to Islam was a Hindu.

The situation is quite different today. There are several people across the world who claim adherence to “Hinduism” according to them. Julia Roberts is a famous example. The definition of Hinduism today is largely a construct of Western scholarship, which describes it as the combination of the many philosophical and intellectual traditions present in India through history. This does not always translate well into the current mode of practice of a majority of Hindus, leading to conflicts between the Western-dominated scholarly view and the Indian-dominated “practical” view. The recent controversy involving Wendy Doniger’s book ” The Hindus: An Alternative History” is an example of this.

The Roots of the Hindu Way of Life

The earliest roots of Hinduism are quite vague. Perhaps the earliest archaeological evidence of practices that closely parallel some practice today comes from around 9000 B.C. in Central India. The site was excavated by a team of archaeologists from India and the United States and they found a Paleolithic site that was a shrine. It was a circle, about a meter across, made of natural stones. In the middle of the circle, lying flat on the ground, with one or two pieces broken of was a naturally triangular piece of sandstone. The sandstone seemed to have triangles inscribed within it.

Astonishingly, the archaeologists had come across several similar shrines in nearby villages that were in use by the villagers. These shrines were dedicated to the earth goddess and were also associated with Shiva, one of the most prominent divinities. The archaeologists sought out the locals and when they approached them with their find, the villagers replied that their shrines were obviously related with what the archaeologists had found. Once the archaeologists had left, the villages built a wall around the ancient site and began to worship there too.

Such shrines are not limited to just this one locality. Even today, many villages across India have shrines to goddesses situated on a small circular raised platform, often at the base of a tree, just as the Baghor shrine was. And triangular artifacts are very much a part of the Hindu way of life even today. Yantras are commonly used even in India today, which are essentially objects created of stone or metal that are a complex combination of several triangles. Yantras are said to bring physical, economic and spiritual well-being.

Much later, in the Indus Valley or Harappan Civilization that thrived from 3000 B.C. till 1800 B.C. in the northern and western parts of the subcontinent, Lord Shiva appears seated in the padmasana yoga posture and surrounded by animals, a reference to one of his aspects as Pashupati or Lord of Animals. Later, with the coming of the Aryans from Central Asia, several strands of the Aryans Vedic system were integrated into the indigenous system that had prevailed earlier. New gods entered the pantheon of this syncretic mix, though some of the old gods probably survived. Shiva was still around, as was the mother goddess, though she had morphed into many forms as Shakti, Parvati, Durga and more. Ritualistic and sacrificial rites grew in prominence in this time, as the priestly class began to play a big role in society. The scriptures including the Vedas and later the Upanishads were also put into writing around the sixth century B.C., a culmination of an oral tradition that may go back beyond six millennia. These scriptures have remained a backbone of the “Hindu philosophy” that still shapes intellectual thought about Hinduism today.

The Gods and Scriptures of Hinduism

Some estimates of the number of Hindu gods run into thousands. Others suggest that innumerable minor gods exist, but there is actually just one true “god” called Brahman. Brahman is also called the all-encompassing One, the Ultimate Reality. The many gods of the Hindu way of life are thus, part of Brahman, as are human beings and all animate and inanimate things in creation.

There is no one holy book for Hindus, such as the Bible of Judaism and Christianity or the Quran of Islam. The scriptural literature of the Vedas and Upanishads serves this purpose to some extent, though even the epics, the Ramayana and Mahabharata are considered sacred. The Mahabharata is sometimes called the fifth Veda. Add to this the Puranas – 18 of them – and the Upapuranas – another 18 – and the various treatises by sages and scholars down the ages, and the subject of a Holy Hindu book gets messier rather than clearer. At the beginning of the twentieth century, western scholars working on ancient Hindu literature tried to isolate a “Hindu Bible” and believed that they were successful in identifying the Bhagavad Gila, but more recent scholars recognize that no single text is most important. There are several sacred writings, all of which add up to the “sacred corpus”.

There are two main categories of Hindu scripture: shruti, “that which is heard,” and smriti, “tradition” or “that which is to be remembered.” The Vedas and the Upanishads fall into the category of shruti. These are considered to be inspired by God and to have been revealed to humankind by ancient sages called rishis.

The shruti texts are an important foundation for Hindu philosophy. The four Vedas – the Rig Veda, Sama Veda, Yajur Veda and Atharva Veda – are the oldest of the texts. They were compiled and added to over many centuries and possibly millennia, and were never written down until around 1200 B.C. However, the oral tradition goes back much earlier, and the date of the first compositions of the oldest Veda, the Rig Veda, are a matter of great controversy. At the latest is stands at around 3000 B.C. At the earliest, possible dates range from 6000 B.C and beyond.

The four Vedas contains hymns, chants, and praises to the gods, and serve as guidebooks for rituals and priestly behavior. They also offer information on magic and charms to bless or curse, and also contain musical notes to be chanted while performing the rituals. The Brahmanas were texts composed after the Vedas. They contain details of the conduct of fire sacrifices. The Aranyakas or “forest books” were composed after this and look at the meaning of these rituals.

The Upanishads are the last of the shruti scriptures, and were put into writing around 700 B.C. “Upanishad” means “to sit in the presence of” a guru or spiritual master. Thus the disciple gains access to the esoteric and mystical. The Upanishads are predominantly presented in the form of dialogues between a student and a teacher. Perhaps the most important concepts of the Hindu way of life were first put into writing in the Upanishads. Karma (one’s destiny is decided by one’s action), samsara (the repetitive cycle of birth and death that a soul goes through), and moksha (release from this cycle of samsara) are found in Upanishads.

Shruti texts are considered more sacred than the other scriptures, smriti, because they are said to be revealed by the divine. The smritis include the epics, the Puranas, Sutras, Shastras, and devotional Bhakti songs. The epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, have had a significant influence on Hindu thought. They have had many layers added to them over the centuries and have changed their form many times.

The Mahabharata contains over 90,000 stanzas and is the largest poem in history.Sage Vyasa is said to have dictated it while Ganesha, the son of Shiva and Parvati wrote it down. The Mahabharata is the story of a fraternal war within the Kuru clan, featuring the five Pandava brothers as the protagonists and the 100 Kaurava brothers as the antagonists. Lord Krishna makes his appearance in the Mahabharata as the divine incarnate and plays a key role in the story. Most significantly, he speaks to Arjuna on the battlefield, and reveals his all-encompassing divine form, the Vishwaroopa Darshan. Krishna’s words to Arjuna form the Bhagavad Gita, which is thus contained within the Mahabharata.

The other great epic, the Ramayana, “the story of Rama”, tells the tale of Rama, the seventh incarnation of the god Vishnu, the one preceding Krishna. The Ramayana depicts the ideals of faithfulness to marriage vows, brotherly affection, and loyalty. The earliest parts of the text date from around 350 B.C., but the work as a whole was not compiled until much later. Both the Mahabharata and the Ramayana have influenced the philosophy of Hinduism for over two thousand years.

The Puranas literally mean “something very old” and are also smriti writings. Written in Sanskrit, these form a collection of verses that tell the stories of the best known Hindu gods and goddesses and the lives of ancient heroes. They include creation stories, portraits of the gods and famous sages, and accounts of time periods that run into scales of billions of years, quite unique among the myths of ancient civilizations.They also speak of the birth and destruction of creation in terms that have astonished physicists with their parallels to modern cosmology. The Puranas also contain the legends of ancient dynasties. They are referred to as the Vedas of the common people, because they present traditional religious and historical material through tales that most people can understand.

Another popular form of scripture is the Bhakti literature. These devotional songs were produced in both southern and northern regions of India, where teachers emphasized the love of those devoted to a personal god or goddess and the love returned by the god or goddess. The Bhakti movement developed a number of poet-sages who sang praises to Hindu gods and goddesses in the languages of the common people. By the sixth century A.D., these devotional hymns were being sung in many temples.

Hinduism Beliefs and Worship

There are several threads that weave together to form the Hindu way of life. For a majority, rituals and poojas form the main part of their worship. Such important rituals and traditions accompany every aspect of life, from birth to death and beyond. Poojas are performed in a sacred corner in a worship room of the home. The most exalted setting for performing puja is the temple. The temple is the house of god and a link between human existence and the divine. It is also the center of social, artistic, intellectual, and religious affairs. Most essentially, for a Hindu, the temple is a place of passage to the non-physical, beyond the process of repeated birth and death.

In their pursuit of moksha, Hindus consider the physical world we perceive as maya or illusion. Maya does not mean that the world does not exist, as is commonly misunderstood today. Rather, maya refers to how the world is not the way we currently perceive it. Our perception of reality is flawed, and thus they live in illusion. To achieve moksha, one must seek inner peace and harmony by breaking the bonds of karma. All human efforts and deeds are subject to the law of karma, and thus this forms a dual-edged sword. In one way, one could sink into suffering as a result of ill-considered action. But one may also rise to an exalted state as a result of positive actions. But all karma, whether good or bad is a trap. Only breaking free from karma can one attain moksha. Moksha cannot be achieved by action aimed at gaining something in this world but only by an experience of oneself as united with god, the oneness of atman-Brahman, the union of one’s self with the Ultimate Reality. All rituals, poojas, yoga and meditation are aimed at this.

The Hindu Way of Life

As early as the Vedic period, Hindu society was roughly divided into four divisions based on occupations – the brahmins or priests, the kshatriyas or warriors, the vaishyas or traders, and the shudras or physical laborers. This basic part of Hindu life is known as the caste system. The Hindu caste system was supported by dharma, early religious laws of duty. Dharma insisted that particular castes had certain duties within the society. An individual, as a member of a caste, was responsible for upholding those duties. However, this system was initially set up as a social system, and was not meant to become a system of discrimination as it has become today. Inter-caste marriages were not entirely unheard of in ancient times, and it was also not unusual for a brahmin or shudra to wrest kingship from the current ruler. Chandragupta Maurya, who established the Mauryan empire which spread over much of the subcontinent was thought to be the son of a laborer.

Within every family and throughout society, individual life is divided into four stages: childhood, youth, middle age and old age. Hindus practice samskara, traditional rites of passage, to mark these important transitions from the moment of conception to the time of death. All rites of passage, including those of death and afterlife, are performed at home by the head of the household. According to tradition, each family member is responsible for maintaining sacred order in the family, in society, and ultimately in the universe, and the celebration of these rites of passage are part of that order. Religious observance of the basic rites (conception and birth, introduction to the guru for initiation, marriage, and cremation after death) are believed to be part of the path that leads Hindus toward their goal of moksha.