Origins of Lady Liberty

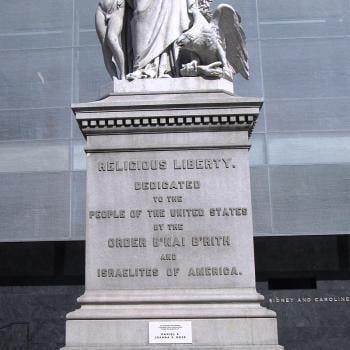

On May 14, 2019, History.com uploaded an essay titled Statue of Liberty: The Making of an Icon:

“The Statue of Liberty, which towers 305 feet, six inches over New York Harbor, is one of the most instantly recognizable symbols of America. It has inspired countless souvenir replicas and been referenced in everything from posters for war bonds to [scenes in various movies] …

Emma Lazarus wrote a poem, ‘The New Colossus,’ which was read at a fundraising art exhibition in 1883. (Two decades later, it was inscribed on a bronze plaque on the inner wall of the pedestal.) Lazarus’ stirring plea to ‘Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free’ helped to make the statue more than just a celebration of American democracy, by linking it with the waves of immigrants arriving in America in the late 1800s, and their aspirations for a better life. …

As Magnuson-Cannady, supervising ranger for the National Park Service tells the ‘Raising the Torch’ podcast, ‘The Statue of Liberty was really of the people in that the people of the United States and the people of France…not the super wealthy, not the super powerful—it was everyday folks contributing to the fundraising efforts and paying for the Statue of Liberty and the pedestal.’ …

The statue became an even more prominent American symbol during World War I, when it became one of the sights that U.S. soldiers gazed upon as they sailed off to fight in Europe, as well as one of the first things they glimpsed when they finally returned home.

… the Statue of Liberty, how it became a symbol of home and democracy during wartime and its global significance as an icon representing equality and immigration.”

The important points are the statue was paid for by the people of France (not the government) as a gift to the people of America, while the pedestal was paid for by the people of America (not the government). The statue itself celebrates freedom, justice, democracy and the aspiration for a better life. The statue was the first thing seen by immigrants sailing in and was a beacon of hope. These days, the statue is immediately recognizable around the world.

On July 10, 2020, Reuters uploaded an article titled Inspiration behind original Statue of Liberty design:

“In 1876, French craftsmen and artisans started construction of the statue in France, designed by sculptor Frederic Auguste Bartholdi as a celebration of the centennial of the U.S. Declaration of Independence.

Bartholdi had proposed a monumental figure of a ‘robe-clad woman representing Egypt’ during the construction of the Suez Canal in Egypt in the 1850s. While Egypt rejected the idea as too costly, Bartholdi’s initial vision of an ‘Arab peasant’ evolved into one of a ‘colossal goddess’ that he’d later apply to his Statue of Liberty design. …

Bartholdi had also studied ancient classical figures of massive proportions. The statue of Helios, also known as the Colossus of Rhodes, influenced his plans for the eventual construction of Libertas, the subject of the Statue of Liberty.

Bartholdi was ultimately not commissioned for the work due to budgetary restraints, but he revisited these early models when designing what is now known as the Statue of Liberty, formally entitled ‘Liberty Enlightening the World’..

The National Park Service confirms that the statue was modeled after the Roman Goddess Liberty, or Libertas, also stating that classical images of Liberty are often depicted in the female form.

The broken chains near the statue’s feet, the NPS states, likely represent breaking free from ‘tyranny and servitude’.

By 1884, the entire statue was completed and put together in Paris, while construction workers, many of whom were recent immigrants, began building the statue’s pedestal on Bedloe’s Island in New York Harbor. The workers who reassembled the statue once it arrived in New York were also largely new immigrants.”

The important points are that the statue represents the Roman Goddess Liberty, or Libertas, and is based on the Colossus of Rhodes, which represented the Greek sun god Helios.

There is a lot of fascinating speculation online as to whose face is actually on the statue. These aren’t relevant to this blog, however, as I’m focusing on the spiritual aspects of the statue.

It has been previously stated that Lady Liberty celebrates freedom, justice, democracy and the aspiration for a better life. These things are just as important now as they were when she was first conceived. To bring her influence into our lives, the spiritual principles encoded within her need to be understood.

Symbols on Lady Liberty

On 8 July 2020, Ranker uploaded All of the Symbols on the Statue of Liberty, Explained:

The Torch: is described by NPS as lighting “the way to freedom, showing us the path to Liberty.”

The Crown chosen by Bartholdi chose was “a spiked diadem or aureole, like that seen in classical images of Helios, the Greek sun god.” The official librarian of the Statue of Liberty National Monument says it’s “a halo or what in art is called a nimbus, showing she is divine.”

The Robe is actually a “stola and pella (gown and cloak), which are common in depictions of Roman goddesses such as Libertas.”

The Seven Spikes (or rays) of her crown have been proposed to represent either the “seven continents” or the “seven seas of the world”.

The 25 Windows in the crown according to NPS represent “gemstones found on the earth.”

The Broken Shackles and axe head at the feet of Lady Liberty represent “the throwing off of tyranny and oppression.”

The NPS writes that statue collectively symbolizes “American independence and the end of all types of servitude and oppression.”

The Tablet of Law (or tabula ansata) in Lady Liberty’s left hand is inscribed with “JULY IV MDCCLXXVI” (July 4, 1776) to recognize the creation of the United States of America.

The Shape of the Tablet is a keystone, which is an architectural stone that “keeps the others together.” The NPS observes that “the keystone of this nation is the fact that it is based on law” and “without law, freedom and democracy would not prevail.”

Her Long Second Toe is a nod to her heritage. Lady Liberty has so-called “Greek feet,” where the second toe is longer than the “big toe.” Some scholars think sculptor Bartholdi gave her “Greek feet” as a way of “defining her heritage from the earliest days of civilization” since it was an “aesthetic preference” for showing off sandaled feet by makers of ancient Greek statuary.

Lady Liberty is not standing still but is walking. This is said to be “symbolic of leading the way and lighting the path to Liberty and Freedom.” There’s an aesthetic reason for her stride, as well. Bartholdi described in his original patent “the right leg, with its lower limb thrown back, is bent, resting upon the bent toe, thus giving grace to the general attitude of the figure.”

The Pedestal represents the power of ancient Europe.

The Shields that circle the pedestal represent the 40 States of the Union

The Southeast Orientation is explained by the NPS in stating that the statue “faces southeast and was strategically placed inside of Fort Wood, which was a perfect base for the Statue” and “was also perfect for ships, entering the harbor, to see her as a welcoming symbol.”

The Square and Compasses can be found on a plaque on Liberty Island as Freemasons built the Statue of Liberty.

The eleven-pointed “Hendecagram” star at the base of the Statue of Liberty is actually just the remnants of Fort Wood. The design existed long before the statue was conceived and is actually a fairly typical pattern for forts.

The Statue of Liberty was conceived, financed, built, and installed by Freemasons. Their legacy, as the above shows, was to encode messages in the statue.

Lady Liberty and the Number Seven

There are 7 spikes or rays on the crown.

The number of windows in the crown below the spikes is 25. Summing the digits, 2+5=7.

There are 16 leaves around the torch. Summing the digits, 1+6=7.

The height of the statue can be rounded to 151 feet tall. Summing the digits, 1+5+1=7.

More accurately, the height is 151 feet and 1 inch, which is 1813 inches

1813 divided by 7 yields 259. Summing the digits, 2+5+9=16, and summing these digits, 1+6=7.

Lady Liberty’s Pedestal

The pedestal was made separately and so is less relevant, but there are a couple of interesting aspects to consider.

The pedestal has 4 Grecian columns on each side, making a total of 16. Summing the digits, 1+6=7.

The eleven-pointed “Hendecagram” star at the base of the Statue of Liberty suggests that the number 11 is important. A number of fun options to explore include that fact that In Thelema, 11 represents the number of magick. On the Qabalistic Tree of Life, the eleventh sephira is the Sphere of Da’ath, the hidden sephira occurring in the middle of the so-called Abyss. 11 is also a master number in numerology.

I will, however, be limiting myself to the number seven.

Libertas

“Libertas (Latin for ‘liberty or freedom’) is the Roman goddess and personification of liberty. She became a politicised figure in the Late Republic, featured on coins supporting the populares faction, and later those of the assassins of Julius Caesar. Nonetheless, she sometimes appears on coins from the imperial period, such as Galba’s “Freedom of the People” coins during his short reign after the death of Nero. She is usually portrayed with two accoutrements: the rod and the soft pileus, which she holds out, rather than wears.”

“The pileus was a brimless, felt cap worn in a number of countries including Ancient Greece, and was later introduced in Ancient Rome.”

According to the Britannica, Libertas was usually portrayed as a matron with a laurel wreath or a pileus. The pileus was given to freed slaves, and hence was a symbol of liberty. While the symbolism of the pileus would have been immediately apparent to Romans, its meaning has been lost, so a substitution makes a lot of sense.

The Greek equivalent of the goddess Libertas is Eleutheria, the personification of liberty. Eleutheria personified had a brief career on coins of Alexandria.

I was unable to find an invocation to Libertas or Eleutheria, but there’s nothing stopping people from writing their own.

It was previously stated that Lady Liberty has so-called “Greek feet,” suggesting that we should look towards her Greek origins. We know that the Lady Liberty statue was based on the Colossus of Rhodes.

Colossus of Rhodes

Colossus of Rhodes statue – 19th century engraving by Sidney Barclay

“Helios was particularly worshipped was at Rhodes, the largest of the Dodecanese islands of Greece in the eastern Mediterranean. There he was the most important deity, their patron god, and honoured by the Halieia festival, the highlight of the island’s religious calendar and a Pan-Hellenic games much like the ancient Olympic Games. …

The man commissioned with the Herculean task of sculpting the giant Helios was Chares of Lindus (a city on Rhodes). The project would not be finished until c. 280 BCE, and as the 1st-century CE Roman writer Pliny the Elder noted, it cost 300 talents and took at least 12 years to complete the bronze figure which stood some 70 cubits or 33 metres (108 ft) high. It is likely that the bronze outer shell, presumably applied in sheets and assembled on site, was supported by internal struts made of iron and certain pieces were weighted with stones to increase the figure’s stability.

Although Helios was usually envisaged and represented in art as a charioteer with a sun-beamed halo riding across the sky and dragging the sun behind him, the Rhodians perhaps went for a more statuesque representation for their colossal figure. Unlike many other super-famous sculptures from antiquity, though, there are no surviving representations or scale models of the Colossus in other ancient art forms to help reconstruct in detail what the Colossus may have looked like. …

The base of the statue carried the following inscription, preserved in the ancient anthology of poetry, the Palatine Anthology (VI.171):

‘To you, Helios, yes to you the people of Dorian Rhodes raised this colossus high up to the heaven, after they had calmed the bronze wave of war, and crowned their country with spoils won from the enemy. Not only over the sea but also on land they set up the bright light of unfettered freedom.’ …

The Colossus, along with many other structures on Rhodes, was toppled by an earthquake in either 228 or 226 BCE. According to the Greek geographer and writer Strabo (c. 64 BCE – 24 CE) in his Geography (14.2.5), the statue snapped at the knees and then lay forlorn and untouched because the locals believed the great oracle of Delphi’s prediction that to move it would bring misfortune on the city.”

“Its massive broken pieces cluttered the docks of Rhodes for a millennium before being melted down as scrap in the mid-7th century CE.”

This indicates that to the people of Rhodes, Helios represented freedom, peace from war, and doubtless a time of prosperity. It’s also important to note that nobody knows what the Colossus actually looked like, but it can inferred that it would have been similar to other representations of Helios.

Helios

Helios in his chariot, relief sculpture, excavated at Troy, 1872; in the State Museums of Berlin

“Helios (Hêlios) was the Titan god of the sun, a guardian of oaths, and the god of sight. He dwelt in a golden palace in the River Okeanos (Oceanus) at the far ends of the earth from which he emerged each dawn, crowned with the aureole of the sun, driving a chariot drawn by four winged steeds. When he reached the the land of the Hesperides in the far West he descended into a golden cup which bore him through the northern streams of Okeanos back to his rising place in the East. …

Helios was identified with several other gods of fire and light such as Hephaistos (Hephaestus) and light-bringing Phoibos Apollôn (Phoebus Apollo).”

While Helios is normally portrayed wearing a crown from which there are numerous rays, there is one admittedly late text which insists that there should be seven rays, which would tie him in with the Statue of Liberty. This, however, is not reflected in most representations we have of him, but does tie him in with the Statue of Liberty.

Nonnus, Dionysiaca 38. 90 ff (trans. Rouse) (Greek epic C5th A.D.) :

“He [Helios] placed the golden helmet [of the Sun] on Phaethon’s head and crowned him with his own fire, winding the seven rays like strings upon his hair, and put the white kilt girdlewise round him over his loins; he clothed him in his own fiery robe and laced his foot into the purple boot, and gave his chariot to his son.”

As a point of interest, “Plato informs us in his Symposium and other works that many people, including Socrates, would greet the Sun and offer prayers each day.”

If you feel that you’d like to work with Helios to bring in the energy of Lady Liberty, you’d be working with him on Sunday, which is the day of the Sun. You’d use frankincense as your incense and the color gold, perhaps via yellow candles? Here is a wonderful invocation to use:

[Mierzwicki, Graeco-Egyptian Magick, 139]Homeric Hymn 31 to Helios [trans. Hugh G. Evelyn-White] [1] And now, O Muse Calliope, daughter of Zeus,

begin to sing of glowing Helios whom mild-eyed Euryphaessa, the far-shining one,

bare to the Son of Earth and starry Heaven.

For Hyperion wedded glorious Euryphaessa, [5] his own sister, who bare him lovely children,

rosy-armed Eos and rich-tressed Selene and tireless Helios who is like the deathless gods.

As he rides in his chariot, he shines upon men and deathless gods,

and piercingly he gazes with his eyes [10] from his golden helmet.

Bright rays beam dazzlingly from him,

and his bright locks streaming from the temples of his head gracefully enclose his far-seen face:

a rich, fine-spun garment glows upon his body and flutters in the wind: and stallions carry him.

[15] Then, when he has stayed his golden-yoked chariot and horses, [15a] he rests there upon the highest point of heaven,until he marvelously drives them down again through heaven to Ocean.

Hail to you, lord! Freely bestow on me substance that cheers the heart.

And now that I have begun with you, I will celebrate the race of mortal men half-divine whose deeds the Muses have showed to mankind.

Apollon

Apollon [Apollôn]: commonly referred to as Phoibos Apollon (Phoibos meant shining or radiant, and referred to his function as a god of light or the sun), was the son of Zeus and the goddess Leto; the twin brother of Artemis; and the god of the sun, presiding over prophecy and oracles; music and poetry; archery, healing, plague, purification, and the protection of young boys. He was comfortable with both his silver bow and his lyre. His epithets were normally understood as meaning striking from afar—he could bring sudden death and disease to men and boys.

Thus, Hekatebolos (strikes from afar, with his bow), Hekebolos (the afar, the distant one) and Hekatos (kills many, with plague). He was described as the most Greek of the gods. He was depicted as a handsome, beardless youth with long hair, but a youth elevated to its ideal, which was manifest in the divine. His symbols included: the sun, a wreath and branch of laurel, bow and quiver, raven, lyre, dolphin, wolf, swan, and mouse.

[Mierzwicki, Hellenismos, 41-2]It is important to note that in Homeric literature, Apollon was clearly identified as a plague-dealer with a silver bow and no solar features. By Hellenistic times Apollon had become closely connected with the Sun in cult and Phoibos, the epithet most commonly given to Apollon, was later applied by Latin poets to the sun-god Sol.

The number seven was sacred to Apollon. He was believed to have been born on the seventh of the [lunar] month, whence he is called hebdomagenês. According to some traditions, he was a seven months′ child (heptamênaios). On the seventh of every [lunar] month sacrifices were offered to him and his festivals usually fell on that day.

The Homeric Hymn to Hermes has a description of Apollon’s lyre – it had a sound-box made from a tortoise-shell. The lyre could be made with up to seven strings, and many, but not all, representations feature this.

It was previously stated that Libertas was sometimes portrayed as a matron with a laurel wreath. Laurel leaves and wreathes are also tied in with Apollon.

The celebrated oracle of Apollo at Delphi has an ancient temple complex which dates back at least 2700 years, and was known throughout ancient Greece. The sanctuary’s priestess (or Pythia) would go into a trance state after chewing laurel leaves and inhaling subterranean vapors.

Apollon was represented wearing a laurel wreath on his head, and wreaths were awarded to victors in athletic competitions, including the ancient Olympics.

It appears Apollon is the closest fit as by late antiquity had been conflated with Helios, thus inheriting all his solar attributes. The number seven was sacred to him, and occurs repeatedly on the Statue of Liberty. Both he and Libertas were portrayed with laurel wreaths.

If you feel that you’d like to work with Apollon to bring in the energy of Lady Liberty, you’d be working with him on Sunday, which is the day of the Sun. You’d use either frankincense or laurel as your incense and the color gold, perhaps via yellow candles? Here is a wonderful invocation to use:

Orphic Hymn 34. For Apollon

Come, blessed Paian, slayer of Tityos;

O Phoibos, Lykoreus, god of Memphis, bright famed giver of wealth, crying “ie!”

With a golden lyre, herdsman, lord of seeds,

Pythios, Titan, Gryneios, Smintheus, slayer of Python, and Delphic prophet.

Wild, lovely, light-bringing daimon, renowned youth, you lead the Mousai in choral dance,

flinging far arrows from a bow, holy finned-one, Didymeus, Loxias working from afar, Lord of Delos.

Your eye sees all and brings light to mortals. Gold haired, you reveal accurate oracular words.

Hear me praying for the people and have a kindly heart.

For you see the boundless Aither, and the rich earth from up above;

and through the dead of night, in still silence, under starry-eyed darkness, you perceive the roots below. You hold the cosmic bounds.

You have concern for the first and the last.

Decked with flowers, you harmonize the poles

with your quick-striking lyre, arriving now at the highest string, then turning downward

to the lowest ones, in the Doric mode;

balancing the poles you draw distinctions between living nations.

In harmony you measure a common share to people,

an equal mix of winter and summer

for each of them; and you pick out the notes:

the lowest with winter, and the highest for summer.

In the Doric mode you play for spring’s much loved and flowery season.

For this, mortals celebrate you in song, and call you Lord and Pan, the two-horned god

who sends forth the whistling songs of the winds.

Wherefore you hold the seal of the cosmos—

hear, blessed one, the initiates’ cry, supplicants, for you to be their savior.

[Translation from Dunn, The Orphic Hymns]The primary reference texts for this article are:

Patrick Dunn, The Orphic Hymns: A New Translation for the Occult Practitioner

Tony Mierzwicki, Graeco-Egyptian Magick: Everyday Empowerment

Tony Mierzwicki, Hellenismos: Practicing Greek Polytheism Today

Tony Mierzwicki

Author of Hellenismos: Practicing Greek Polytheism Today and Graeco-Egyptian Magick: Everyday Empowerment.