A number of online sites state that the Autumn Equinox represents the return of Persephone to the underworld, but how accurate is this?

As a typical example, on August 15, 2019, History.com uploaded an article titled Fall Equinox which stated:

“To the ancient Greeks, the September equinox marks the return of the goddess Persephone to the darkness of the underworld, where she is reunited with her husband Hades.”

The Abduction of Persephone

Persephone [Persephonê] was the goddess queen of the underworld, wife of the god Haides [Haidês] (Hades). She was also titled Kore (Core) (the Maiden) and was the goddess of spring growth. Persephone was worshipped alongside her mother Demeter in the Eleusinian Mysteries. This agricultural-based cult promised its initiates passage to a blessed afterlife.

“Persephone was usually depicted as a young goddess holding sheafs of grain and a flaming torch. Sometimes she was shown in the company of her mother Demeter, and the hero Triptolemos, the teacher of agriculture. At other times she appears enthroned beside Haides.”

Seated goddess, probably Persephone on her throne in the underworld, Severe style ca 480–460, found at Tarentum, Magna Graecia (Pergamon Museum, Berlin)

Persephone was the daughter of Zeus and his sister, Demeter [Dêmêtêr], who in turn was the middle daughter of Kronos and Rhea. Demeter’s name means ‘Mother Earth’. She was considered the mother of corn, or of all crops and vegetation, and consequently of agriculture and growth. Demeter also presided over fertility, nature, and the seasons.

Demeter’s most important myth concerns the rape of her daughter Persephone by her uncle, Haides, lord of the Underworld. Zeus, without the knowledge of Demeter, had promised Persephone to Haides, and while she was gathering flowers, the earth suddenly opened and she was carried off by Haides.

Her cries were heard only by Hekate and Helios. Demeter searched ceaselessly for Persephone, during which time the earth was infertile and famine-stricken. As all life on earth was threatened with extinction, Zeus sent Hermes to the underworld to fetch Persephone. Haides released her, but gave her a pomegranate, which bound her to him for one third of the year when she ate the seeds. Persephone’s time in the underworld corresponded with the unfruitful times of the year, and her return with springtime.

The best-known mystery school was the Eleusinian Mysteries, which focused on the worship of Demeter and her daughter, Persephone. The Eleusinian Mysteries were practiced for a thousand years, and were available to anyone who could pay the fees, including women, noncitizens, and slaves. Only murderers and those unable to speak Greek were excluded, which meant that they were very inclusive. Athens imposed the death penalty on those who divulged the Eleusinian Mysteries, and so very little is known about them. Those who were initiated, however, were assured of a blessed afterlife. It has been suggested that ‘all important rites of Demeter in Attica seem to have been linked (at least loosely) to stages of the agricultural year.’ This would tie in the Eleusinian Mysteries and the other major festivals with the sacred cycle of grain production.

[Mierzwicki, Hellenismos, 29, 38]It is interesting to note that while earlier writers stated that an agreement was made that Persephone should spend one third of every year with Haides, and the remaining two thirds with the gods above, later writers stated that it was half of every year.

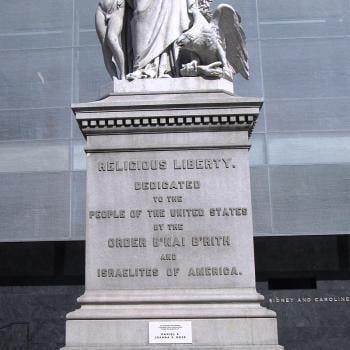

The abduction of Persephone 360-350 BC British Museum London

Athenian State Religious Calendar

There was no single standard calendar in ancient Greece. There were a number, but the best-known one was the Athenian state religious calendar. It consisted of lunar monthly festival days concentrated at the beginning of each month and annually recurring festivals.

In the Athenian calendar, the first day of the lunar month was called the Noumenia. In its broadest context, the Noumenia honored all the deities and symbolized new beginnings. The Noumenia began in the evening when the young lunar crescent first became visible, which was either the day after the dark moon or the day after that.

The Athenian calendar was actually a lunisolar calendar, as each date indicated the lunar phase as well as time within the solar year. The general consensus is that the Athenian calendar began with the Noumenia after the summer solstice.

Thus, regarding the two solstices and two equinoxes of the year, only the summer solstice was determined with precision. While people would have been aware of roughly when the winter solstice and the two equinoxes occurred, there was no need to know their exact dates as there were relevant festivals celebrated within a few days of those dates.

The Athenian calendar normally consisted of twelve months, each being either 29 or 30 days long. This would correspond to a lunar year of 354 days that was 11¼ days short of the solar year. By way of compensation, the Athenians resorted to intercalation, which meant introducing an extra month every third, sixth, and eighth year.

The Athenian months were named after various festivals. The month spanning September/October was called Pyanepsion (from the boiling of the beans).

[Mierzwicki, Hellenismos, 109-10, 115, 171-3]Pyanepsion

Pyanepsion is the lunar month which contains the autumn equinox. While this month contains numerous festivals, I will summarize those pertaining to Demeter and Persephone.

Pyanepsion takes its name from the feast of Pyanepsia, which is derived from the words for beans and boiling. While the dish obviously contained beans, cereals were also included. This dish was usually called panspermia (all seeds), and the ingredients were all boiled together in one pot.

Pyanepsion 6:—The Proerosia (preliminary to the ploughing) was a festival to Demeter, where Apollon at the Delphic Oracle commanded that Athenians should offer portions of their barley and wheat crops to Demeter at Eleusis. Thus, Demeter’s blessing was sought prior to ploughing and sowing. Those of us with home gardens or even a few potted plants would be wise to take advantage of Demeter’s blessing.

An example of a dish that was dedicated to Demeter at this time was called galaxia (barley and milk porridge).

Pyanepsion 9:—The Stenia marked the ascent of a group of women to a temple of Demeter. The women celebrated by verbally abusing each other by night.

I would be wary of reintroducing a ritual involving verbal abuse unless the women knew each other sufficiently to know that no malice was intended. In these modern-day politically correct times, some people seem to be less resilient to verbal abuse.

Pyanepsion 10:—Thesmophoria (later addition)

Pyanepsion 11:—Thesmophoria day of the Anodos (the way up)

Pyanepsion 12:—Thesmophoria day of the Nesteia (fasting)

Pyanepsion 13:—Thesmophoria day of the Kalligeneia (goddess of the beautiful birth)

The Thesmophoria, the Proerosia and the Pyanepsia all had seed-time connections. The Thesmophoria was observed almost throughout the entire Greek world and honored Demeter. It was the only festival that allowed participating women to leave their homes all day and all night. It was preceded by sexual abstinence and characterized by a pig sacrifice, for which it was apparently permissible to substitute a votary. The first day was known as the way up to the Thesmophorion on a hilltop. That evening piglets [or votives in the form of piglets], dough fashioned into snakes and phalluses, and pine branches would be thrown into the chasms of Demeter and Kore. The decayed remains of these sacrifices, called thesmos, when mixed with seed would ensure a bountiful harvest. The second day, called fasting, involved the women laying on makeshift beds consisting of plants reputed to quell the libido strewn on the ground, during which they remained in the presence of Demeter. The fasting came to an end on the third day with a meat banquet. Kalligeneia, the goddess of the beautiful birth, was called upon.

The women would also eat pomegranate pips, the red juice of which was associated with blood.

[Mierzwicki, Hellenismos, 109-10, 115, 171-3, 185-9]It should be noted that while she is only explicitly mentioned once, Kore/Persephone is constantly by Demeter’s side during spring and summer, ensuring bountiful harvests. While the obvious emphasis is petitioning Demeter and Persephone to producing abundant crops, there is also a petition for painless childbirth. The reference to eating pomegranate can also been seen as a reference to Persephone’s underworld association.

It should also be noted that all the festival dates pertaining to Demeter and Persephone are indexed to the lunar calendar. Nowhere is there any explicit reference to the autumn equinox, but the festival dates are in close proximity to it.

Demeter. Coarse-grained marble, Roman artwork; the head is a modern restoration.

Should Persephone be called on at the Autumn Equinox?

The point of this blog was to show that while the ancient Greeks did not honor Persephone precisely at the Autumn Equinox, their festivals were within a few days.

There will be purists who will insist that Persephone and Demeter should only be called on as the ancient Greeks called on them. To those already working with a lunar calendar, or those prepared to go online to find what the relevant dates in the month of Pyanepsion correspond to in September and October, this is certainly a wonderful option.

However, given how busy many people are, the reality is that many will be informed through social media or a news channel that the autumn equinox is at hand. This will hopefully be enough of a trigger to honor Persephone and Demeter. If seasoned properly, a hearty meal of beans and grains is quite filling and serves as a reminder that harvest time will soon be upon us. A porridge of barley and milk (or a non-dairy milk) makes a wonderful offering to Demeter, especially when sweetened with honey and sprinkled with perhaps a dash of cinnamon. I’d be inclined to offer pomegranate to Persephone.

Personally, I’d rather see the gods invoked non-traditionally than ignored. The important thing is to have the right intent, focus and to come from the heart. Invocations should be read with emotion and not like rattling off a shopping list.

The Rape of Proserpina [Persephone] by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1621-22) at the Galleria Borghese in Rome.

Then while focusing on bountiful harvests the following invocations can be used:

Orphic Hymn 29. For Persephone

Come, Persephone, daughter of great Zeus, blessed one, only begotten goddess.

Accept these gracious offerings to you.

Many-honored wife of Plouton, you give life diligently, and control the gates of Hades,

beneath the depths of the Earth.

Praxidike, with lovely locks of hair:

Holy child of Deo, and the mother of the Furies, queen of the Underworld,

maiden whom Zeus sired with ineffable seed—

you are the mother of loud-roaring and many-formed Eubouleus.

The shining and luminous playmate of the seasons,

honored and mighty, maid bursting with fruit.

Mortals long for you alone, bright, horned,

spring time goddess, who is delighted with meadow breezes,

revealing your holy body in the green and yellow new shoots.

In autumn, you were seized and forced to wed.

Now you, Persephone, alone are life and death to toiling mortals,

for you feed us always, and also kill everything.

Hear, blessed goddess, and send up the fruits from the earth,

blossoming in peace and with the soothing hand of health,

and a rich life that leads old age, sleek and shining, downward,

queen, to your kingdom, to mighty Plouton.

[Translation from Dunn, The Orphic Hymns]

Orphic Hymn 40. For Eleusinian Demeter

Incense: storax

Deo, divine mother of all, daimon with many names, Demeter,

nourisher of the young and bestower of blessings,

wealth-granting goddess and giver of all,

nourisher of ears of grain, who delights in peace and in hard work too, the sower,

thresher, who heaps up grain, and brings green fruit,

you dwell in Eleusis, in holy vales;

charming, lovely, who feeds all mortal things,

who first yoked cattle with sinew to plough,

and produced a lovely, prosperous life

for mortals, causing things to grow: Bright-famed,

you share your hearth with Bromios.

Bearing light, you rejoice in the scythes of summer.

You are terrestrial, you show yourself,

and you are kind to all. Blessed with child,

you love and nourish children, o holy youth.

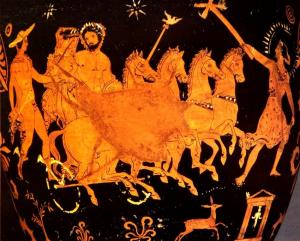

And to bridled dragons, you yoke up your chariot,

and in whirls you conduct them in frenzied circles around your throne.

Divine only daughter, but with many children;

to mortals, a mighty lady of many forms, flowery and blooming.

Come, blessed and holy, heavy with the fruits of summer,

leading down peace and lovely order, rich wealth, as well as queenly health.

[Translation from Dunn, The Orphic Hymns]The primary reference texts for this article are:

Patrick Dunn, The Orphic Hymns: A New Translation for the Occult Practitioner

Tony Mierzwicki, Hellenismos: Practicing Greek Polytheism Today

Tony Mierzwicki

Author of Hellenismos: Practicing Greek Polytheism Today and Graeco-Egyptian Magick: Everyday Empowerment.