Are there lessons we can learn from the practice of democracy by the ancient Athenians?

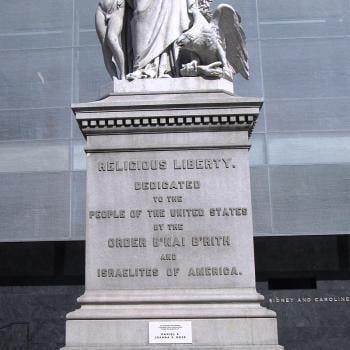

Solon defends his laws against criticism from Athenian citizens, painting by Noel Coypel, 1699.

History of democracy in Greece

Many of the core values of Western civilization can be attributed to the Greeks, including democracy and the right of individuals to have freedom of speech.

The classical Greeks, or Hellenes, considered themselves different from the surrounding peoples. They referred to non-Greeks as “barbarians” [barbaroi], which literally meant foreigners—people who could not speak Greek. It was not just a matter of language; it was a matter of a different lifestyle and a different way of thinking. The Greeks thought of themselves as free, as they lived in a democracy where they were part of the decision-making process. Foreigners were thought of as virtually slaves, living under the rule of monarchs. In a sometimes mistranslated verse, the poet Pindar (518–c. 446 BCE) in Nemean (6.1–6) stated that gods and men were of one race and had one mother. Yet, in terms of power, men were nothing while the abode of the gods in the heavens endured forever. This was effectively the tragedy of man—dignified, yet weak.

[Mierzwicki, Hellenismos, 2, 21]

In the Archaic Period (eighth to sixth Century BCE), the Greeks lived in numerous individual city-states, each of which consisted of a hereditary ruler and the heads of the main families who owned the land. In each of these city states, the king was originally vested with political and priestly authority. Following revolutions royalty lost its political power, reverting to a priesthood. In Politics Book 3, Aristotle stated that while kings originally had absolute power, some renounced it, while others had it taken away from them, leaving them in care of the sacrifices. Plutarch in Roman Questions 63 gives a similar account. Herodotus provides an example from the city of Cyrene in the form of Battus, a descendent of the kings, who lost all the power of his fathers, but took care of worship. This meant that political power lay in the hands of powerful aristocratic kin groups (genos, singular). Power was finally taken away from the aristocracy and given over to the citizenry by the politician Kleisthenes, the “father of democracy,” in 507 BCE. Each citizen’s political identity became a product of his father and the deme to which they belonged. The Athenian political system was then able to represent the interests of all citizens. As a matter of interest, it has been argued by some academics that ancient Greek democracy actually emerged in the course of the sixth century, long before Kleisthenes’ reforms, throughout Greece as well as in the colonies.

[Mierzwicki, Hellenismos, 89-90]

During the so-called Golden Age (480–399 BCE), Attica (the city state encompassing Athens) had a population of 315,000. Power was in the hands of 43,000 citizens who were males aged twenty-one and over, with two free Athenian parents, and who did not engage in manual labor and were not subject to anyone. These were the only people who had the right to vote and enjoy the fruits of democracy. Thus, democracy was limited to about 14 percent of the population. The remainder of the population consisted of free Athenian women and children, 115,000 slaves, 28,500 metics (metikoi, or resident aliens), freedmen (those who were once slaves), those who had to labor for a living, and those who were subject to another. Very few slaves in Greece were Greeks—most were foreigners. Even the poorest citizens had one or two slaves, while the richest homes had fifty or more.

[Mierzwicki, Hellenismos, 134-5]

Athens was engaged in war with Sparta and her allies from 431–404 BCE, whereupon Athens was captured. After her defeat, Athens lost its democratic government and instead had a commission of thirty citizens. This failed within two years and democracy was reestablished.

From this time on, no Greek city-state was able to create a united empire. Phillip II, King of Macedon, with its semi-Greek population living in northern Greece, came to power in 359 BCE. He set about conquering many Greek city-states, organizing them in a league under Macedonian control until his assassination in 336 BCE.

Upon Phillip’s assassination, his son, Alexander, came to the throne at the age of twenty. Alexander reigned until his death in 323 BCE. He left an empire stretching from the Aegean to the Indus River, encompassing Greece, Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Persia. After Alexander’s death the empire was Hellenized by introducing a common language, and allowing trade and travel for intellectuals and artists. Religions were blended throughout the empire, but the most influential was the Greek religion.

The Hellenistic age is often defined as beginning with Alexander’s conquest of the Persian Empire in 331 BCE until Octavian’s defeat of Antony and Cleopatra at Actium in 31 BCE. It can be argued that the Hellenistic age ended earlier than this for Greece. Rome became the most powerful city in Italy in 295 BCE, whereupon it began expanding into Greek territories. Greece was finally annexed by Rome, with the sacking of Corinth in 146 BCE.

[Mierzwicki, Hellenismos, 90-1]

Can we apply ancient Greek democracy today?

Much within ancient Greek religion was noble, but it was part of a cultural milieu, or social environment, that entailed animal sacrifice, occasional human sacrifice, slavery, the subordination of women, the practice of magick, and copious drug use. Greek religion was a product of its time, and as such was paralleled by numerous other religions. Times have changed, and there is a clear need for adaptation. Thus, Hellenismos should not be a reconstruction of ancient Greek religion as it was, but rather a reconstruction of what Greek religion plausibly would be had it survived. It is known that the religion changed in ancient times in response to changing needs as time passed, and so it would have kept changing had it survived until today.

[Mierzwicki, Hellenismos, 3]Athenian democracy was definitely a step in the right direction, but it was a product of its time and fell short of what it should have been. Had ancient Greek religion survived I would hope that slavery would be a thing of the past. I would also hope that democracy would be available to all legal citizens, regardless of gender, wealth, and whether they were naturalized or descended from Athenian parents. Thus, democracy would be available to 100 percent of the population, rather than just 14 percent.

In the following we will be looking at an annual festival to celebrate democracy. Perhaps this festival should be recreated at times when it is required as well as annually?

Athenian celebration of democracy

In Summer, the Athenian state religious calendar included the month of Boedromion (named from a festival for Apollon the Helper) in August/September.

On Boedromion 12, the Athenians observed Democratia, which was their celebration of democracy. Greek religion was seamlessly integrated into everyday life, so such a festival should come as no surprise. Democratia included sacrifices to Zeus Agoraios, Athene Agoraia and to the Goddess Themis. Images of Zeus and Athene were paraded in the agora below the Acropolis.

Zeus Agoraios and Athene Agoraia were guardians of the agora which was a central public gathering space in ancient Greek city-states – the center of the athletic, artistic, spiritual and political life in the city. In later times it became a marketplace, where merchants and artisans could sell their wares. Themis was the goddess of divine law.

Parading images of Zeus and Athene publicly won’t be practical for most people, so a discrete offering at a home altar, (perhaps a libation?) would probably work best, in conjunction with the recitation of a hymn. Contemplating the benefits of living in a democracy, and the importance of not taking it for granted would make for an effective ritual.

A simple ritual would take the form of:

Make an offering to Zeus Agoraios, recite Orphic Hymn 14 [and possibly Homeric Hymn 23].

Make an offering to Athene Agoraia, recite Orphic Hymn 31 and [and possibly Homeric Hymns 11 and 28].

Make an offering to Themis, recite Orphic Hymn 78.

[Mierzwicki, Hellenismos, 3, 173, 183]

The following is some background information and the relevant hymns for the deities being worked with.

Zeus

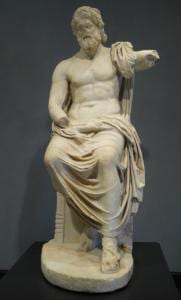

King of the Gods, Zeus, at the Getty Villa. Roman, Italy, A.D. 1 – 100.

Zeus [Zeus]: described by Homer as the father of gods and men; the god of justice and the sky.

Zeus is the Sky Father, a rain and storm god. He is of clear Indo-European origin, with his name being similar to the Indic sky god Dyaus pitar and the Roman Diespiter/Juppiter, as well as having connections to the weather gods of Asia Minor. The Homeric epithets of Zeus were the cloud gatherer, the dark clouded, the thunderer on high, and the hurler of thunderbolts. He is the strongest of the deities and other deities are fearful of his thunderbolts, which destroy whatever they strike. Even in Mycenaean times he was considered to be one of the most important, if not the most important of the deities.

Olympus, the dwelling place of Zeus, is on mountains where the clouds gather. This was eventually narrowed down to the highest mountain in Thessaly.

According to Hesiod’s Theogony, prior to Zeus’ reign, the world was ruled by Zeus’ father, Kronos, and his fellow Titans. Worried about being usurped by his son, Kronos swallowed all his children as they were born. Zeus’ mother, Rhea, saved him by giving Kronos a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes to swallow.

A Cretan Theogony, written after Hesiod, stated that the infant Zeus was raised in a cave on Mount Dicte in Crete by two nymphs. Outside the cave were youthful warriors known as the Kouretes beating their spears against their shields to prevent Kronos from hearing Zeus.

Once he reached maturity, Zeus, armed with his thunderbolts, led the gods to victory in battle against the Titans. As a result, Zeus was typically called upon to give victory on the battlefield.

Zeus with his lightning, Poseidon with his trident, and Hades with his head turned back to front were the three powerful sons of Kronos who drew lots for the division of the cosmos after defeating the Titans.

Zeus was very well known for his sexual exploits, sharing his bed with a slew of goddesses and mortal women, with late mythographers counting. He did not, however, limit himself to women, as he abducted the Trojan youth Ganymede. Zeus would often shapeshift into a number of animals, birds, and even golden rain, as part of his seductive technique. He was the only god to father powerful gods and goddesses, namely Apollon, Artemis, Hermes, Persephone, Dionysos, Athene, and Ares. Zeus was referred to as father by all humans and deities, whether or not he had actually sired them.

In art, Zeus was represented as either a warrior hurling a thunderbolt with his right hand, or as a king seated on a throne holding a scepter. He was associated with the eagle and with bull sacrifices.

His usual symbols included a thunderbolt, royal scepter, eagle, oak tree, and pair of scales.

[Mierzwicki, Hellenismos, 34-5]

Orphic Hymn 15. For Zeus

Incense: storax

Much honored Zeus, immortal Zeus, we bear this freeing testimony and this prayer.

O king, these divine things shine through your head:

the holy mother earth, and loud sounding slopes of mountains;

the sea, and all things, as many as the heavens array within.

Kronian Zeus, holding your scepter, you send down thunder, fierce in spirit,

father of all, the first and the end of everything.

Earth-quaker, increaser, purifier, the vibration of all things.

The lightning, thunder, and the bolt, o nourishing Zeus.

Hear me, the god of many forms, and give unto us faultless health, and divine peace,

glorious prosperity without blame.

[Translation from Dunn, The Orphic Hymns]

Athene

“Mattei Athena”. Marble, Roman copy from the 1st century BCE/CE after a Greek original of the 4th century BCE, attributed to Cephisodotos or Euphranor. Related to the bronze Piraeus Athena.

Athene [Athênê]: commonly referred to as Pallas Athene. (Depending on the tradition, Pallas was either a relative or companion, or a nymph, whom Athene accidentally killed as they practiced combat skills. A mournful Athene then took the name Pallas for herself.) Her name may also have been taken from the appellation of a Mycenean warrior-goddess who was her predecessor. She was the daughter of Zeus and the Titan Metis; the goddess of wisdom, women’s handicrafts including weaving and spinning, courage, heroic endeavor, strategic warfare, and protectress of cities.

Athene’s father, Zeus, swallowed her mother, Metis (Titan goddess of wisdom, skill, or craft), while she was pregnant. Athene sprang from Zeus’ head fully armed. She was a virgin with shining eyes, normally portrayed armed, crowned with a crested helmet, armed with shield and long spear, and wearing a goat-skin cloak [aigis] adorned with the monstrous head of the Gorgon. Her symbols include the owl and the olive tree.

[Mierzwicki, Hellenismos, 44] [The Gorgons were three powerful, winged daimones named Medousa (Medusa), Sthenno and Euryale. Of the three sisters only Medousa was mortal. King Polydektes of Seriphos once commanded the hero Perseus to fetch her head. He accomplished this with the help of the gods who equipped him with a reflective shield, a curved sword, winged boots and helm of invisibility. When he fell upon Medousa and decapitated her, two creatures sprang forth from the wound–the winged horse Pegasos (Pegasus) and the giant Khrysaor (Chrysaor). Perseus fled with the monster’s head in a sack and her two angry sisters chasing close on his heels.]

Orphic Hymn 32. For Athena

Incense: aromatics

August Pallas, who sprang from Zeus alone,

divine, blessed goddess, with a powerful heart,

who stirs the turmoil of war,

your name is mighty, spoken and unspeakable.

Dwelling in caves, you rule the hills, valleys,

high flowing streams, and shadowy mountains

and you gladden your breast in shady vales.

Delighting in weapons you sting the souls of mortals to madness, exhausting them.

Maiden, having a horrible anger,

Gorgon-slaying, shunning the marriage bed,

yet the abundant mother of the arts.

Loving frenzy, you urge on the wicked to madness, but give wisdom to the good.

You are both male and female in nature,

the wise mother of war. Ever changing dragon, filled with divine power,

splendid in honors, you destroyed the Phlegraian giants.

Horse-driving Tritogeneia, you deliver from evils,

o daimon bearing victory always day and night,

and even in the smallest of the hours.

Hear my prayer, and give us a rich measure of peace and health, in prosperous seasons,

grey-eyed, creative queen to whom all pray.

[Translation from Dunn, The Orphic Hymns]

Themis

Chairestratos: Themis. Marble, c. 300 BC. Found in Rhamnonte, at the temple of Nemesis. Dedicated to Themis by Megacles. National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

“Themis was the Titan goddess of divine law and order–the traditional rules of conduct first established by the gods. She was also a prophetic goddess who presided over the most ancient oracles, including Delphoi (Delphi). In this role, she was the divine voice (themistes) who first instructed mankind in the primal laws of justice and morality, such as the precepts of piety, the rules of hospitality, good governance, conduct of assembly, and pious offerings to the gods. In Greek, the word themis referred to divine law, those rules of conduct long established by custom. Unlike the word nomos, the term was not usually used to describe laws of human decree.

Themis was an early bride of Zeus and his first counsellor. She was often represented seated beside his throne advising him on the precepts of divine law and the rules of fate.”

Orphic Hymn 79. For Themis

Incense: frankincense

“I call on Themis, the holy daughter of her noble father, Ouranos, and offspring of Gaia,

the maiden whose face is like a budding flower, who first showed mortals the holy oracle,

giving prophesies to the gods from the abyss in Delphi on the Pythian plain where King Python ruled.

She taught the lord Phoibos the oracles.

All honored, lovely-shaped, revered, roaming the night,

you brought holy rites to light for mortals for the first time,

shouting to the lord throughout the Bacchic nights.

For the honors of the blessed ones and the holy mysteries come from you.

But, blessed maiden, kindly come, welcomed to holy rites of your solemnity.”

[Translation from Dunn, The Orphic Hymns]

The primary reference texts for this article are:

Patrick Dunn, The Orphic Hymns: A New Translation for the Occult Practitioner

Tony Mierzwicki, Hellenismos: Practicing Greek Polytheism Today

Tony Mierzwicki

Author of Hellenismos: Practicing Greek Polytheism Today and Graeco-Egyptian Magick: Everyday Empowerment.