One has to have some sympathy for the abbots who directed the Abbey of Gethsemani during Thomas Merton’s time there, for Father Louis—as he was known within the monastery walls—must have tried their patience at times. He was a most unusual monk, a fact that became steadily clearer over time.

That said, Merton greatly improved the fortunes of his new home. When he came to Gethsemani in 1941, the abbey was struggling financially. Within a few years, that situation steadily improved as Merton’s books brought in royalties and new novices started arriving at the door, many of them inspired by Merton’s writings.

In the early years, some of his fellow monks had no idea that Father Louis was the same person as Thomas Merton. There’s a funny story told of a new arrival having his initial interview with Merton, who served as novice master at the time. Merton asked what had drawn him to explore a monastic life, and the man replied that he had been influenced by Thomas Merton’s work. “What do you think of it?” Merton asked, and the man went on to give some positive comments as well as a list of criticisms. It wasn’t until the next day that he learned that he had been criticizing the author to his face (one suspects Merton was greatly amused by this).

Merton biographer William H. Shannon says that to him the great miracle of Merton’s life is that he stayed at Gethsemani: “That this sophisticated young man with all his worldly interests, not to speak of his undisciplined life heretofore, could accept the rigors of this kind of monastic life and indeed thrive on them is at once proof of the validity of this lifestyle and a sign of the grace of God operating in this young monk.”

Merton himself believed that a monastic vocation isn’t chosen. Instead, “it picks you,” he wrote.

When Merton entered the monastery, he believed that as a contemplative he would have to give up his writing (he had already written several unpublished novels). We have his superiors to thank for their insistence that the two were not in competition—indeed, that writing could be a help to contemplation. Writes Shannon:

“Had Merton been forced to stop writing he would have shriveled up as a monk, perhaps even left the monastery. God does not give gifts for us to throw them away. Moreover, if Merton had persisted in believing (if he ever really believed it) that were he to use his gift as a writer he could not be a contemplative, his most important message for the contemporary world would have been muted. For if one cannot be both a contemplative and a writer, it would follow that one could not be both a contemplative and a housewife, a contemplative and a truck driver, a contemplative and a teacher, a contemplative and a worker on the assembly line.” (from Thomas Merton: An Introduction).

By the early 1960s, Merton was steadily expanding his circle of connections outside the monastery walls. He came to see that his monastic life did not absolve him of his larger responsibilities in the world or prevent him from commenting on the great issues of the day, including war, prejudice, economic injustice, and racism.

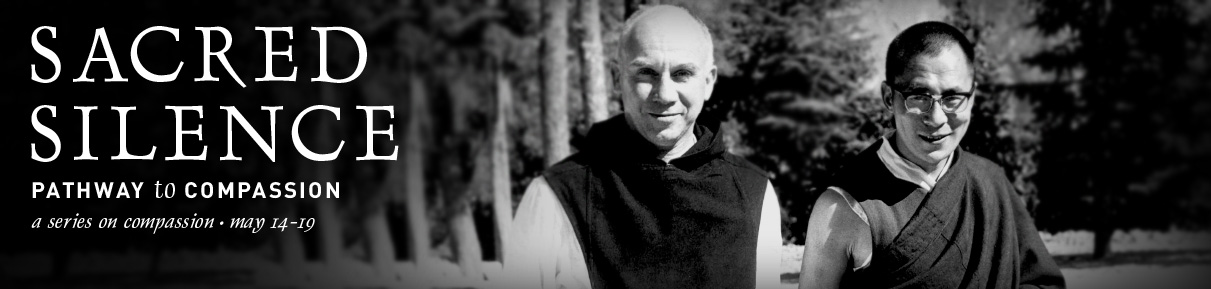

Merton’s life at the abbey was not without trials. In his early years there, he struggled with the sense that another monastery might be a better fit for him. Throughout his time as a monk, he experienced tension between his desire for solitude and contemplation and his love for human company. For years he asked for permission to have his own hermitage in the woods, a request his abbot finally granted in 1965 (Merton thus became the first American Trappist allowed to live by himself as a hermit). While the simple cinderblock house allowed him greater time for prayer and writing, he also welcomed a steady stream of visitors, including the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh, the French philosopher Jacques Maritain, and Chilean poet Nicanor Parra.

There’s a bit of a paradox in all of this, isn’t there? One of the famous criticisms of Merton, in fact, was that he wanted to be a hermit just so long as his hermitage was in Times Square with a neon sign above it announcing “Hermit lives here!”

But as William Shannon says, God does not give gifts for us to throw them away. Merton’s gifts included the ability to relate to many kinds of people, a love for conversation and dialogue, a passionate engagement with political and social issues, and a talent for writing. He made use of all of them brilliantly, even within the monastery walls.