Some of you have perhaps seen the beautifully carved Maori marae, or meeting house, in the Field Museum in Chicago. Until traveling to New Zealand, I didn’t understand the full significance of what it represents. Even more than a church is for Christians, a marae (pronounced ma-rye) is the heart of Maori society, a place for communal gatherings and a storehouse for tribal traditions. The elaborate carvings that often adorn their exteriors and interiors tell stories and trace genealogies. The space inside is a place of tapu (sacredness).

We visited a number of marae in New Zealand, but my favorite experience came at one located on the island of Waiheke near Aukland. We visited there on a program led by TIME Unlimited, which has won international awards for its indigenous tourism programs. The company is owned by Ceillhe and Neill Sperath. Ceillhe is a New Zealander who proudly claims both Maori and Irish blood (with that combination, how could I not find her charming?).

“During your time here, we want the marae to become your home,” she told us. “This is meant to be a family experience, for once you are officially welcomed, you become part of us.”

After the welcome ceremony we spent the rest of the day and evening in activities that included a trip on a waka (canoe) in the bay, native plant weaving, and the preparation of the hangi, a meal cooked over hot stones buried in the earth. At night, we slept in sleeping bags on the floor of the beachside meeting house, listening to traditional songs and stories as night fell.

But mainly what we did was talk—about Maori families, religion, food, healing, ceremonies, art, and childrearing. In addition to Ceillhe, our guides included a half-dozen Maori who patiently answered our endless questions (if you host a group of writers, I guess you have to expect being inundated with questions). By the time I fell asleep that night, I felt that my knowledge of Maori culture had grown exponentially.

I want to tell you about one of our guides in particular, a man named Gazza. I first saw him on the ferry ride to the island. Even among the hundred or so people who crowded the boat, this man was difficult to miss, for he was literally covered in tattoos. Every visible part of him had been inked with elaborate swirls and colored patterns, including his face and shaved head. He was also muscular and stocky, a man you wouldn’t want to meet in a dark alley.

So it was a surprise when we reached the island and I learned that the Tattooed Man was not only part of our group—he was one of our guides. And in speaking to him, I found that he was not frightening at all. In fact, he is a gentle and deeply spiritual man.

It turns out that the tattoos I had seen as bizarre and frightening were in fact the result of a religious vision. Gazza said that four years ago he had received a vision of an eagle in the night, a bird so huge that it filled his bedroom. The eagle came back to him five nights in a row, until finally Gazza gave in. He knew what he was being called to do, because at 20 years of age he had received an earlier vision, one that had showed him the tattoos that would one day cover his head. “I held out as long as I could,” he said.

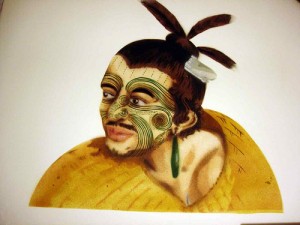

So Gazza went to a tattoo artist and had his face, lips, and head marked with elaborate designs, which in the Maori language are known as ta moko. In doing so, he was following a revered Maori tradition, for tattooing has been a valued part of their culture for many centuries. And because the head is considered to be the most sacred part of the body, to wear tattoos on the face is the ultimate statement of one’s Maori identity.

As Gazza told his story, I became more and more fascinated. He explained the symbolism of his markings, describing how one arm told the story of his mother’s lineage and the other one that of his father, and how his facial tattoos were patterned after those of Maori warriors of the past and how they symbolized the flow of the spirit from the sky to his mind and out through his mouth. As he spoke, I came to realize that Gazza was an evangelist for his tradition.

In fact, I learned that this man I thought might be a gang member is employed by the New Zealand Ministry of Education to teach Maori culture in Aukland schools, and that he also mentors Maori adolescents in the criminal justice system. He teaches them about the spiritual traditions of a culture that has been buffeted and damaged by the modern world, but one that still holds great riches.

I loved how my expectations were turned upside down by Gazza. Do I want to be visited by an eagle in the night telling me to tattoo my head? Not so much. But I think I can learn something from his story—about how important it is to be true to one’s identity, and about how strength and gentleness are not mutually exclusive.