Up to this point I’ve said very little about a central feature of traditional Maori culture: its close connection to nature. Though the modern world has altered those ties in some ways, there remains a deep spiritual link between the Maori and the incredibly beautiful land and seas of New Zealand.

That tie was most obvious on our tour of the Northland region of New Zealand. Located on the northern tip of the North Island, this locale once was covered with dense semitropical rainforests. Only a small fraction of that landscape remains, but those remnants are absolutely remarkable.

One species of tree dominates this forest: the kauri. These trees are found only at a certain latitude in the western Pacific and are exceedingly slow growing. They make up for their dallying by growing for a long, long, long time. By the time they’re mature, the kauri are second in size only to sequoia, reaching heights of nearly 200 feet.

When Europeans came to New Zealand, they began harvesting these magnificent trees, which were valued not only because of their beautiful and durable wood but also because of their resin, which had a wide variety of industrial uses. The giants were felled, one by one, and the lumber was shipped across the sea.

On our tour, we first toured the Kauri Museum in Matakohe. Exhibits there describe how the trees were harvested, including how the massive logs were transported out of the forests by damming rivers until the water was high enough to carry out the felled trunks. The museum is chockfull of treasures, from exquisite antique furniture made from kauri wood to exhibits on the lives of the lumberjacks who felled them (say what you will for the environmental damage they caused, there’s no denying these were hardworking and brave men). The museum’s most striking display is very simple: on a wall is traced the circumference of the largest kauri trees ever found (most measured only from their stumps, alas). Their size is so immense that it seems almost impossible that such trees exist.

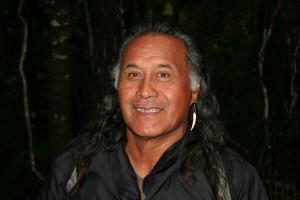

Then we traveled to the Waipoua Forest, which preserves a stand of kauri that because of its inaccessibility was never logged. Our guides were Koro Carman and Bill Matthews of Footprints Waipoua, a Maori-owned company that leads trips into the forest. Their goal is to explain why these trees are so significant ecologically and why they are considered sacred by the Maori.

“The Maori believe that it was the kauri tree that created life,” Koro told us. “When Father Sky and Mother Earth were locked in a passionate embrace, it was the kauri tree that separated them, creating space for light.”

Led by Koro and Bill, we drove to the outskirts of the forest. Before entering the woods, Bill said a prayer in Maori, asking for protection as we walked. Then we started off on a hike that took us to the two greatest trees of all: Te Matua Ngahere (the god of the forest) and Tane Mahuta (the lord of the forest).

Evening was falling as we hiked on a path that wound through thick underbrush. As we walked, our guides pointed out the kauri trees that we passed, each one more immense than the last. “That one is a baby, just eight hundred years old,” they said of one. “This one is a thousand years, still pretty young,” they said of another.

And then we came down into a slight ravine where we could see the glimmer of a white trunk ahead of us through the bush. Bill, who was walking behind us, began to sing in Maori, a song picked up by Koro at the front. As we approached Te Matua Ngahere, their song of greeting and praise wove a spell that still makes me shiver when I think of it.

Step by step we approached this 3,000-year-old tree, which is so massive that it wasn’t until we were fairly close to it that I could even see its top towering above the lower canopy of lesser trees.

I’m not sure how to describe those minutes standing in front of that tree. I’ve stood before redwoods and sequoias and been awed by them as well, but seeing this ancient remnant of a race of giants was profoundly moving in a way that went deeper than words. I know that if I’m allowed to take only a handful of memories to the grave, I would include this one, standing there in front of that tree, listening to the Maori men sing, sensing that something wild and wise and mysterious was in front of us.

God of the Forest, indeed.