Today’s post is a sermon I gave in my home church this past Sunday (some of this will be familiar to regular Holy Rover readers). It explains, among other things, why I enjoy Happy Hour so much with my husband:

Let me begin by telling you a story, one that proves yet again that books can change lives.

In 1521 in Spain, a young man was recuperating from injuries he had received in a battle. He was bored and restless after many months spent convalescing in bed. Normally he liked reading adventure stories, but after having read all of those books in his parent’s library, his boredom led him to start reading books about the lives of Jesus and the saints. He was surprised that he found them interesting, for he had paid little attention to religious matters before. But as he read the stories, he grew more and more fascinated. A desire began to grow in him to become as dedicated a servant to God as he had been dedicated to the life of a soldier.

The young man was Ignatius of Loyola, a saint typically associated with the Roman Catholic Church. But I think it’s a mistake to allow our Catholic brothers and sisters to keep him to themselves, because we Episcopalians can learn much from his life and teachings.

After his spiritual awakening, Ignatius of Loyola gave up his life as a knight to immerse himself in study and prayer. He made pilgrimages to Jerusalem and Rome and gathered like-minded seekers around him. He had an extraordinary gift for both friendship and leadership, and eventually founded the Society of Jesus (a group that has come to be known as the Jesuits). During his lifetime, he became particularly well-known for his skill in advising people on their spiritual lives. He eventually gathered those insights into a manual he called the Spiritual Exercises, one of the most influential of all Christian texts. William James, the American philosopher of religion, described him this way: “St. Ignatius was a mystic, but his mysticism made him one of the most powerfully practical human engines that ever lived.”

A group of us here at Trinity have been benefiting from the legacy of this dynamo of spiritual energy. We’ve been taking part in an on-line retreat based on his Spiritual Exercises, a set of meditations and prayers that have been used by millions of Christians. While the Spiritual Exercises are traditionally done over a 30-day retreat, they’ve been adapted in many ways, including an on-line version offered by the Chicago Province of the Society of Jesus. (See An Ignatian Prayer Adventure. Another excellent resource is James Martin’s The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything: A Spirituality for Real Life.)

Even if you’re not interested in trying the Exercises, I think we can all learn something from Ignatian spirituality, especially during this season of Lent. I’m not sure we Episcopalians do a very good job of teaching people about prayer. We talk about it a lot in the abstract and practice it in our corporate worship, but when it comes down to the details of the various techniques and traditions, we assume that people can discover what they need on their own.

Ignatius took the opposite approach. He was a practical man, and he knew that people needed tools if they were to deepen their spiritual lives. So the Spiritual Exercises are a kind of smorgasbord, a set of meditations, prayers and techniques that Ignatius said can be adapted as needed to fit various situations. This flexibility is a key part of Ignatian spirituality, for Ignatius was a big believer in doing whatever worked. As one contemporary Jesuit describes this approach, we need to pray as we can, not as we can’t.

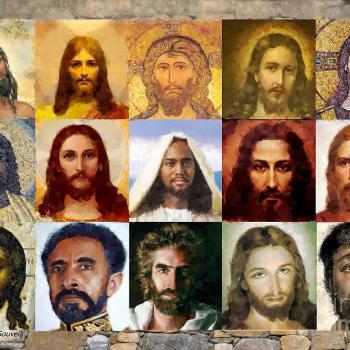

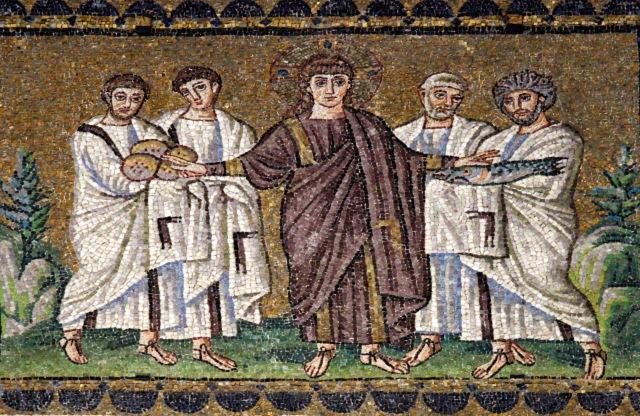

One of the techniques Ignatius recommended is imaginative prayer. He invited people to enter into the Gospel stories with all their senses. Pick a story—for example, the feeding of the 5,000. Imagine that you are there in the crowd, feeling the hot sunshine of a Galilee summer on your face. What do you see around you? What clothes are you wearing? What do you hear? What do you smell? What kind of basket is being passed to you full of fish and bread? How does that food taste? Ignatius believed that when we engage our senses and our imaginations, the Gospel stories become embedded in us in a way that goes much deeper than simply reading them (this approach, by the way, has much in common with our Godly Play religious education program).

While this form of prayer was not new, Ignatius nevertheless was revolutionary in the emphasis he placed upon it. In his time and ours, the imagination is often viewed with suspicion. After all, how can we know we aren’t imaging something false? And what worth is there to idle speculation and daydreaming? But Ignatius believed that our imaginations are given to us by God and that they can be a powerful tool in our spiritual development.

Ignatius also believed that people’s innermost desires are important. Like imagination, desire has a bad reputation in religious circles, where it’s often equated with wayward sexual desires or superficial material wants. But Ignatius thought that our deepest yearnings are also God-given, placed within us so that we can use them to draw closer to him. The purpose of prayer is not to suppress desire, therefore, but to put us in touch with our deepest desires. Think of the times when Jesus asks those who approach him, “What do you want me to do for you?” He is inviting us to search in our hearts for what we most desire.

Most of all, Ignatius believed that God is to be found in all things, even in the most ordinary of moments, and that in order to be aware of that presence, we must be reflective about our experiences. That’s why he advocated a form of prayer that is known as the Examen, a word that shares the same root as examination. At least once a day—typically before bed or just after rising—he recommended that his followers prayerfully review the previous day.

Ignatius told his Jesuits that if they did only one prayer a day, this was the one. Just as we can learn from studying a piece of scripture, this prayer invites us to study our lives as a spiritual text. Or think of it as rummaging around in a box full of miscellaneous items, trying to find something valuable that we know is there. Amid all the clutter, we are searching for what we most need.

While I appreciate many aspects of the Spiritual Exercises, the one thing I am most grateful for is learning this method of prayer. It is an invitation to savor each day. It has even become part of my evening routine with Bob, when we sit and have a glass of wine and rummage through the boxes of our day together, looking for the moments that were most meaningful.

Let me tell you a bit more about the steps of the Examen prayer:

- The first step is to center yourself and pray for illumination. One Jesuit author starts his daily meditation this way: “Lord, help me understand this blooming, buzzing confusion.”

- The second step is to review your day with gratitude. We are to walk through the previous day, from hour to hour and place to place, thinking of all that we have to be thankful for. On a bad day, you might have to scramble for something to say (for example, thank God that meteor in Russia didn’t land on my house). Other days might be full of things to be grateful for. But each day, we are to give thanks for something.

- The third step is to pay attention to your emotions as you replay the day, for our feelings, positive and negative, point to what is important to us. As we review our day, we may feel anger, fear, peace, regret, compassion, or uncertainty.

- The fourth step is to choose one of these feelings, either positive or negative, and pray from it. That feeling is a sign that something important is going on in our lives. Allow yourself to consider what that emotion indicates about your life.

- And finally, the fifth step is to look forward to the coming day. Think of what is ahead of you, the appointments, the tasks, the meetings. What feelings surface for you as you think ahead? Whatever emotion you feel, turn it into prayer, asking God for whatever you need, be it help, healing, understanding, or patience.

There’s a wonderful image used by Jesuit Peter-Hans Kolvenbach to illustrate why the Examen is important. He reminds us that in the book of Exodus, God says to Moses, “You cannot see my face; for no one shall see me and live.” It is only as God passes by that Moses is allowed to see God’s back. The Examen prayer recognizes the truth of that insight. Often it is only when we look back over our lives that we can see the passage of God. That recognition of divine grace often comes later, sometimes much later.

This approach to spirituality, then, is firmly rooted in the world. It respects people’s lived experience. It doesn’t require us to retreat from society in order to find God. And on a lighter note, it’s explains the truth behind an old joke told about the Jesuits. It seems that members of three different religious orders were celebrating mass together one day when the lights suddenly went out in the church. The Franciscan, a follower of St. Francis, began to praise God for the chance to live more simply. The Dominican, a member of an order devoted to teaching, gave a learned homily on how God brings light to the world. And the Jesuit went to the basement to fix the fuse.

This practical approach explains why Jesuits are active in the world rather than housed in a monastic cloister. Throughout history they have been diplomats, scholars, social activists, scientists, and writers. While they have often stumbled, as all Christians do, the Jesuit ideal is to be contemplatives in action. A line from the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, himself a Jesuit, illustrates this. He wrote: “The world is charged with the grandeur of God. It will flame out, like shining from shook foil.” Like all Jesuits, Hopkins believed that God is at work everywhere and visible everywhere, if we only open our eyes to see.

Most of all, Ignatian spirituality asserts that God is searching for us even more than we are searching for God. Think of the many Gospel stories that illustrate this divine characteristic, from the shepherd who searches for the one lost sheep out of the hundred to the widow searching for her lost coin. James Martin, a contemporary Jesuit author, writes that his favorite image for this aspect of God actually comes from the Islamic tradition. In the Hadith, a collection of sayings from the prophet Muhammad, God is quoted as saying this:

And if [my servant] draws nearer to me by a hands breadth, I draw nearer to him by an arms-length; and if he draws nearer to me by an arms-length, I draw nearer to him by a fathom; and if he comes to me walking, I come to him running.

So let me close with the most famous prayer associated with Ignatius of Loyola, this soldier turned mystic, this deeply spiritual yet practical man, this dynamo of energy who invites us to study the book of our lives to see God at work:

Take, Lord, and receive all my liberty,

my memory, my understanding

and my entire will,

All I have and call my own.

You have given it all to me, and to you, Lord, I return it.

Everything is yours; do with it what you will.

Give me only your love and your grace, that is enough for me.

Amen.