Today’s post by Bob Sessions continues yesterday’s book review of Daniel Klein’s Travels with Epicurus: A Journey to a Greek Island in Search of a Fulfilled Life:

I first encountered Klein’s book in a piece he wrote for CNN called Dancing Into Old Age. I was intrigued by what he had to say in the essay, and once I started reading his book, I was hooked from its first pages as well. I can’t recall another book of philosophy that made me smile and laugh as much as this one. He spoke directly to my experiences and delighted me with the easy way he interweaves philosophical teachings with personal anecdotes and stories.

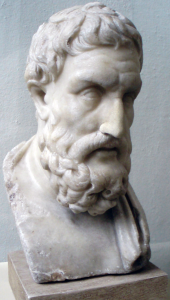

So why should we be interested in a long-dead Greek philosopher who is remembered (if at all) as someone who advocated a hedonistic pursuit of pleasure?

The answer, in part, is that the popular conception of Epicurus is wrong. When many people today hear the word epicurean they imagine someone devoted to pursuing pleasure, especially through the eating of sophisticated and delicious food. While there’s a nugget of truth in this, the full story of Epicurus is much different.

In the third century BCE, Epicurus founded a school (which today we might call a commune) called “The Garden” in Athens. He was a hedonist, yes, but don’t forget that hedonism not only says that pleasure is good, but also that pain is bad. You can maximize your pleasure by seeking pleasure or by reducing pain, or both. A wise hedonist also realizes that some pleasures are better than others, and therefore one must choose them carefully.

So Epicurus’ two key principles are aponia, the absence of pain, and ataraxia, peace and freedom from fear. He believed that the best way to maximize one’s joy in life is to live simply, which involves reducing your needs and desires (our basic sources of suffering). This frees you to approach whatever you do with full time and attention. For him, this meant being surrounded by friends most of the time. He practiced a radical egalitarianism of both gender and social class, with women as well as men welcome around his table. Klein describes Epicurus’ life this way:

Epicurus was a man who lived his philosophy…He and a small and devoted group of friends lived simply, grew vegetables and fruit, ate together, and talked endlessly–mostly, of course, about Epicureanism. Anyone who wished to join them was welcome, as evidenced by the words inscribed on the Garden’s gate: ‘Stranger, here you will do well to tarry; here our highest good is pleasure. The caretaker of that abode, a kindly host, will be ready for you; he will welcome you with bread, and serve you water also in abundance, [and greet you] with these words: ‘Have you not been well entertained? This garden does not whet your appetite, but quenches it.”

Not exactly a gourmet menu, but the price was right and the company intriguing.

This emphasis on the importance of friendship is one of Klein’s central insights from his time in Greece. Epicurus understood, as psychologists today are only just beginning to realize after extensive study, that our happiness is best found in mutual relationships with no ulterior motives except to enjoy being with each other. In scene after scene in his book Klein describes old friends being together playing cards, dancing, admiring women from afar, sitting together gazing in silence at the sea, and many other simple activities that have the single goal of enjoying life together.

The climactic story of the book is (no surprise here) a Greek feast. What Klein, a secular Jew, comes to realize is that this feast is both democratic and spiritual in the best sense of those words: everyone of good will is welcome, regardless of background or status. What matters is not how “Epicurean” the food or wine, but rather how wonderful the company. And that company is made wonderful when the feast is ruled by Epicurus’ epithet: “It is impossible to live a pleasant life without living wisely and well and justly, and it is impossible to live wisely and well and justly without living a pleasant life.”

My own version of Epicurus’ Garden, I’ve come to realize from reading this book, happens every other week when I meet with a group of men friends over breakfast at a local cafe. Over several years we’ve become friends with the waitresses (they know my order without being told) as well as deepened our ties with each other. Over endless cups of coffee we solve the world’s problems, share our joys and sorrows, and laugh about the absurdities of life. So far none of us has danced on the table, but the amount of pleasure we take in each other’s company might compel us to do so one day.