In my travels around the world I’ve learned that most spiritual sites have layers upon layers of history, meaning and mystery. Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado may be the best example I’ve encountered of just how complicated the intertwining of those layers can be.

When I was planning my visit, I contacted the park staff to say that I was a writer interested in learning about the spiritual traditions of Mesa Verde. I got a diplomatically worded reply, telling me in the nicest possible way that I had no idea just how difficult that seemingly simple request was.

The staff at the national park has good reason to be wary of the minefields of interpretation that exist at Mesa Verde. The people who once lived there left no written records. The Indian tribes that trace their ancestry to them are fiercely protective of their own spiritual traditions, many of which derive from what was once practiced at Mesa Verde. And so when clueless travel writers like myself arrive full of questions, there’s an understandable reluctance to be too speculative in their theorizing.

That said, over several days Bob and I learned a great deal, helped out by knowledgeable rangers, some fascinating tours and a wonderful book by Craig Childs called House of Rain: Tracking a Vanished Civilization Across the American Southwest. Over the next few posts I’ll tell you some of what we learned, with the caveat that all of what I write is tentative and partial. But I am certain of this: Mesa Verde and the surrounding area is a spiritual treasure, worthy of pilgrimage. And what’s the value of a holy site that has no mysteries?

Mesa Verde National Park preserves more than 4,500 archeological sites left by a civilization that used to be known as the Anasazi. That term has now fallen into disuse, for it’s derived from a Navajo word meaning “ancient foreigners” and bears no resemblance to what the people actually called themselves. Instead, those who lived at Mesa Verde are now called the Ancestral Pueblo people, for their descendants include the Hopi of Arizona and the peoples of the Zuni, Laguna, Acoma and Rio Grande pueblos of New Mexico.

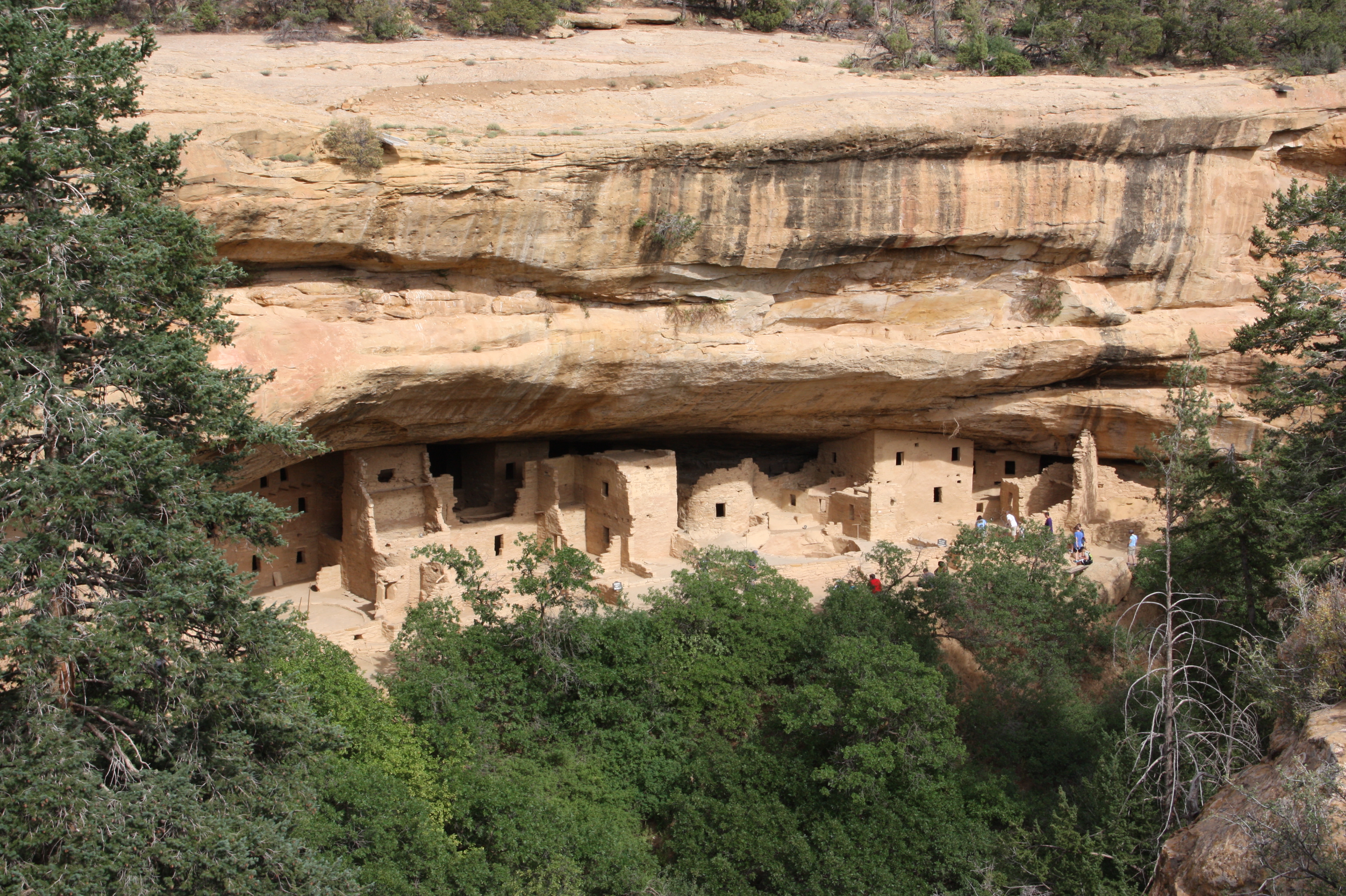

These Ancestral Pueblo people lived at Mesa Verde for seven centuries beginning around 550 C.E. At first they dwelled in shallow pit houses excavated from the soil, but over the centuries they became master builders, constructing elaborate complexes tucked into the sandstone cliffs of this dry region in southwestern Colorado. Because these structures blend so seamlessly with their surroundings, you may not even see them at first when you scan the landscape, until you look more closely and see how cleverly they are built into the rocks.

Why did they build the cliff houses? Archeologists have a variety of theories. Perhaps they were trying to defend themselves from rival tribes. Maybe the buildings were a way to cope with the region’s extremes of temperature, from blistering sun in the summer to the cold winds of winter. Or perhaps these people simply enjoyed the stunning views from way up high. Whatever the reason (or reasons, for probably there were many), the Ancestral Puebloans built a wide array of structures ingeniously fitted into the confines of the surrounding cliffs. Some likely held just a few people and others, such as Cliff Palace and Long House, have 150 rooms and would have housed approximately 100 people.

While the Ancestral Puebloans lived tucked under the cliffs, they clearly didn’t stay there all the time. Using precarious hand- and toe-holds chiseled into the canyon walls, they traveled back and forth to the mesas above, where they hunted for game and grew corn, squash and beans. They also raised domesticated turkeys, which were valued both for their meat and their feathers.

Bob and I got a sense for the high-altitude vibe of life at Mesa Verde on a tour of the Balcony House, which is reached by climbing a 30-foot ladder propped against a cliff. After gingerly ascending the ladder, we emerged into a living space that seemed more like an aerie for birds than a home for humans, with a sweeping expanse of canyon visible from the balcony in front.

“How did you live here if you were afraid of heights?” I asked Bob, a bit dizzy as I peered over the edge.

“The ones who were scared of heights probably didn’t last very long,” he said.

The height wasn’t the only challenging part of living in Balcony House. While visitors today enter via a ladder, in ancient times it was accessible only via a brick tunnel, a narrow passageway that is just big enough to crawl through on your hands and knees. Why this was constructed in such a way is just one of a myriad of mysteries at Mesa Verde. (How did they haul in food and other supplies? What if you were elderly?) Perhaps the tiny entry was a way of keeping out enemies, though surely the day-to-day inconvenience must have been incredible. Or maybe Balcony House was a center for ceremonial activity and its inaccessibility was linked to its symbolic meaning.

As I crawled through that narrow tunnel on our way out of Balcony House, I recalled that in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, one has to bend low to get through an opening known as the Door of Humility. It is a way of physically enacting the spiritual process that one is to go through to become worthy to enter a holy place. Perhaps that was true at Balcony House as well, and the narrow passageway was just the first of a series of tests that one had to go through to be part of the community there.

Balcony House is one of about 600 cliff dwellings in the park. Many have yet to be fully excavated and documented, but enough is known that archaeologists regard the Mesa Verde civilization to be among the most culturally, artistically and religiously sophisticated cultures in pre-Columbian North America.

One of the great mysteries of Mesa Verde is why it was abandoned in a relatively short time period. In the late 1200s people began to move away and by about 1300 Mesa Verde was deserted. This period coincided with an extended period of drought, so perhaps that was the reason for their flight. Or maybe the natural resources of the area had become depleted, the game over-hunted and soils leached of nutrients. Or perhaps it was simply that this formerly nomadic people, a culture that was used to picking up stakes and moving on, moved because there were other places where the figurative grass looked greener.

For whatever reason, Mesa Verde fell into a prolonged slumber and it wasn’t until the late 1800s that the larger world became aware of the ruins. Scientific work began soon after, with pioneering archeologists working to investigate and stabilize the structures. In 1906 it became a national park, the first to preserve an archeological site. Today it is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, part of the patrimony of all humans.

As I toured the ruins, I thought many of the rooms had a surprisingly modern feel, as if they were high-rise apartments waiting for the return of their residents, who would soon come back to sweep away the dust and begin housekeeping once again. But in thinking back to my time there, I find myself returning again and again to that narrow portal that led into the Balcony House. It lent a dreamlike feel to my visit there, making it an almost Alice-in-Wonderland sort of experience. What was it like to live perched high above the earth like that? And why did it feel like there was still a living presence in the ruins of Mesa Verde?