Every so often I come across a book I read very slowly. I want to savor every sentence, wring every bit of meaning out of each line, and think deeply about how the words apply to my life. Kathleen Dowling Singh’s The Grace in Aging: Awaken as You Grow Older

Every so often I come across a book I read very slowly. I want to savor every sentence, wring every bit of meaning out of each line, and think deeply about how the words apply to my life. Kathleen Dowling Singh’s The Grace in Aging: Awaken as You Grow Older

is one of those books.

First, let me acknowledge that it has a somewhat clunky title. It sounds frightfully earnest, doesn’t it, like the literary equivalent of bran cereal? And books on aging don’t exactly fly off the shelves, unless they’re ones on how to slow down the process of growing older.

Singh’s book is meant to appeal to those who don’t want to live their last decades on spiritual autopilot. Her central premise is that aging (whether you’re 40 or 90) is an opportunity for spiritual awakening.

In chapters that include meditations on Withdrawal, Silence, Forgiveness, Humility, Presence, and Commitment, Singh explores Buddhist teachings in an accessible way. This may be the single best book I’ve ever read on Buddhism (or perhaps it’s just that I’m more open to the truths of Buddhism now than I’ve been in the past). But Singh’s gentleness, insight and wisdom will teach you a great deal even if you’re a member of another faith or follow no organized religion.

“Are we willing to leave this unimaginably precious gift of a human life unopened?” she asks in the book, explaining that growing older gives us a wide range of triggers for awakening. Many of these opportunities we likely see as negatives. If we’ve relied on beauty or power for status in the world, inevitably they will fade as we age. If we lacked the time for spiritual practice when younger, illness or disability may give it back to us. If much of our life has been spent feeding the ever-hungry ego, growing older gives us the chance to look at what we’ve mistakenly nurtured with such care.

Confronting our mortality, writes Singh, is jet fuel for our spiritual practice.

Dying, of course, lurks behind all discussions of aging. No party, however fun, lasts forever. One can see this essential fact as depressing and tragic–and certainly in individual cases it is, and Singh doesn’t suggest we short-circuit the natural process of grief, either for ourselves or for the loss of a loved one. But if done well, a person at the end of his or her life moves through the classic stages of spiritual growth to surrender into the grace in dying.

Writes Singh: “What we will observe, if we have the privilege to be present with someone at the end of his or her life, are the following special conditions: opening to mortality, withdrawal, silence, solitude, forgiveness, humility, the practice of presence, commitment, life review and resolution, opening the heart, and opening the mind. Those of us who are still living can take powerful lessons from the dying. Each of these special conditions is a powerful catalyst for transformation. They release us from grasping to self. Working skillfully, we can introduce and make use of these conditions in the midst of life, in these very chapters of being old. Just as these special conditions facilitate the grace in dying, they can lead us directly into the grace in living.”

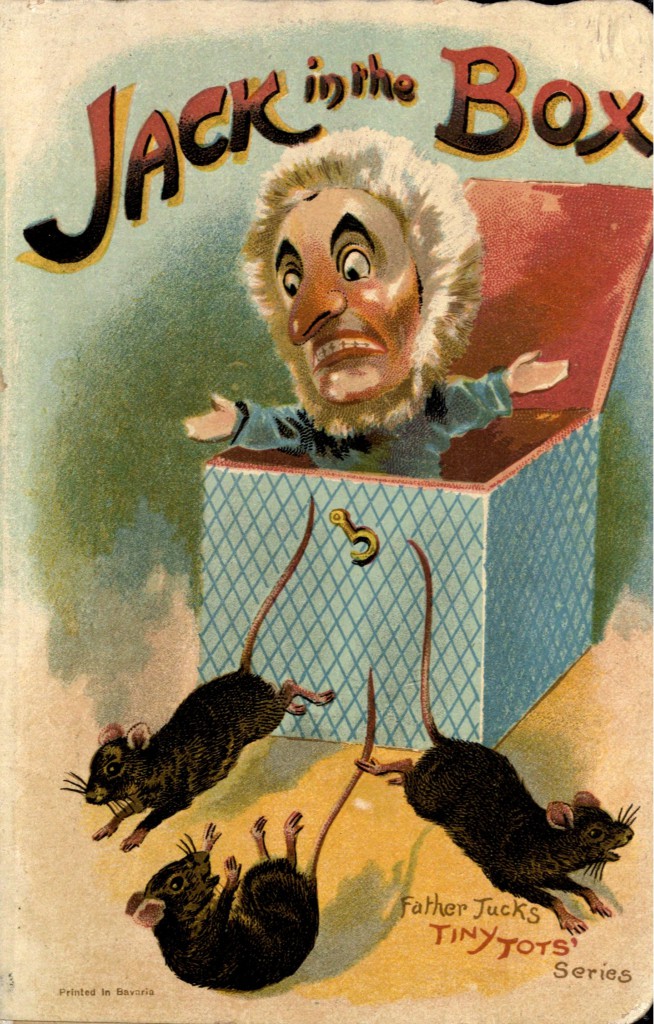

Singh uses a memorable image to illustrate how many of us live. We are like jack-in-the-box toys, she says, each of us reacting the same way when we feel threatened or insecure. Our thoughts and habits are like that clown bouncing up again and again from his box. We each have our clown of choice: anger, self-pity, a need for approval, a seeking after control, a desperate clinging, or jealousy. These are our habitual escape routes, well-traveled paths that condition our responses to whatever we confront.

I’ve been thinking about my own jack-in-the-box a lot since reading this book. Singh doesn’t present a magic formula for keeping that stupid clown from re-emerging when I least expect him, but I think I am a little less automatic in letting him loose.

“How many of the finite number of breaths that I will breathe in this lifetime remain to me?” Singh asks. “This next inbreath. Will it come? This next outbreath. Is it the last? We are very present in such moments. There is no frivolity. Nothing inessential sweeps us back into dull and clouded mindlessness.”

Let me end with one of my favorite passages in the book:

“It’s a bit chastening to see how often we can think, after rising from a meditation or sitting or teaching, ‘Now . . . back to the real world.’ It’s important to rise slowly. It’s important, if we have so chosen, to remember that the intention to awaken encompasses every moment. No moment can be excluded.

There is, initially in a practice and for quite a long time afterward, a dynamic of compartmentalizing our spiritual life. We rope off many corners and many rooms in that vast, interior castle.

We want to resist that decades-old impulse to fall back into the dream of self, the sleep of form only. It’s very helpful to look at the areas of our lives that we wish to cordon off or that we don’t choose to view with the eye of spirit. What’s off limits? Is it work? Relationships? Family? What we do for relaxation? Is it vanity? Is it attachment? Or grudges? Or fears? Shame or other unhealed aspects of our psyche? It’s good to know what we hold as not available for inquiry. There lies our ignorance.

Eventually, as we continue to engage these last years for spiritual practice, we come to see that every moment, every interaction, every circumstance arises from the ground of being. Every moment is one of the places where our feet make contact with the noble path.”