So the Celts knew the power of the spoken word (see A Pilgrimage to St. Patrick’s Day–Part 2). And after the coming of Christianity, they transferred that respect to the written word.

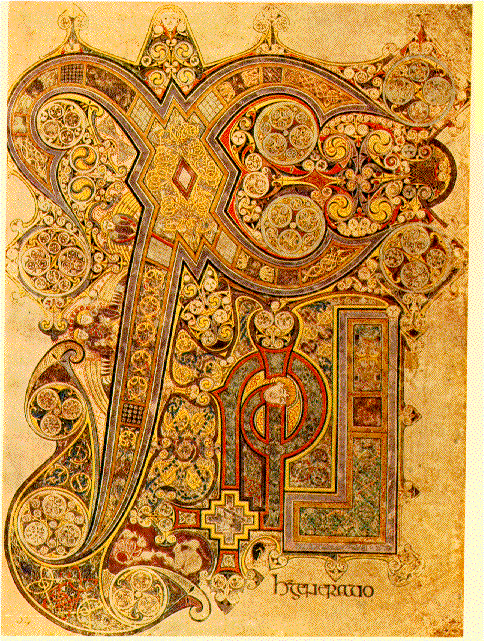

In the eighth century, Celtic Christians created a masterpiece of religious art called the The Book of Kells, a book whose vividness, color, and artistic mastery reflect Christian traditions laced with Celtic enchantment.

The Book of Kells is an illuminated Latin manuscript of the four Gospels. While scholars don’t know for certain, it was likely created on the remote island of Iona off the coast of Scotland, and later brought to the monastery at Kells, Ireland.

Made from the finest vellum and painted with inks and pigments from around the world (including lapis lazuli from Afghanistan), the book is almost indescribable in its loveliness, with designs that are convoluted, ornate, sinuous, and dreamlike in their complexity. Some scholars have called it the most beautiful book in the world.

I remember that when I saw the Book of Kells in Dublin a number of years ago, I felt nearly overwhelmed by it. Before you get to the book itself, you walk through exhibits where the light is dim and the walls contain enlarged images of the book’s pages, backlit so that you can see every detail.

There are all the images you would expect to see in an illuminated manuscript—pictures of Christ and the saints—and ones that surprise and delight, from mythical creatures like dragons and sea serpents to playful cats, darting dogs, and even mice fighting over a piece of communion bread (see below). The sensuous colors leap off the pages, brilliant blues and reds and golds and greens interwoven in complex knots and swirling ribbons.

Most curious of all is this: some of the decorations in the Book of Kells are so ornate that they can only be fully seen with a magnifying glass, even though such lenses were not available at the time the book was created.

Isn’t that marvelous? Just think of those scribes working without artificial light or modern tools, laboring month after month, year after year, to create an object so precious and sacred.

But not so sacred that they couldn’t have a little bit of fun with it. That’s the Irish sensibility at work, no?

A twelfth-century description remains the best summation of the magnetic power of the Book of Kells:

“There are almost innumerable … drawings. If you look at them carelessly and casually and not too closely, you may judge them to be mere daubs rather than careful compositions. You will see nothing subtle where everything is subtle. But if you take the trouble to look very closely, and penetrate with your eyes to the secrets of the artistry, you will notice such intricacies, so delicate and subtle, so close together and well-knitted, so involved and bound together, and so fresh still in their colorings that you will not hesitate to declare that all these things must have been the result of the work, not of men, but of angels.”