For years my long-standing interest in Native American cultures had a large gap: the Pueblo Indians of the Southwest. Our recent trip to New Mexico enlightened some of that ignorance, thanks to two sites that I’ll describe today.

The first is the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, which was founded in 1976 by the 19 pueblos of New Mexico. There I learned that while these Indians have considerable diversity in their languages and customs, they have a common name given to them by the Spaniards. In the 16th century, these indigenous groups lived in settlements made of adobe and divided into apartments with numerous rooms. Many of these dwelling places were located on top of mesas, the high table lands that rise from the desert floor of the Southwest. The Spanish word for “town” was used to describe these settlements, and the name has been used to describe the various tribes ever since.

While their ancestors were nomadic, over the centuries most Puebloans had become farmers, growing corn, squash and beans as well as other crops. They also became skilled potters and basketweavers, traditions which continue to this day.

The Indian Pueblo Cultural Center’s exhibits begin with a description of the origin story of these cultures. Long ago, their ancestors lived in a series of underworlds below the earth. With the help of the Spirits, these people eventually emerged into the current world, founding communities that include Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon. Their lives were cyclical, based around a seasonal calendar of planting, harvesting, dances, and ceremonies. To this day the Pueblo Indians believe that ancestral Spirits continue to guide them and that their land is full of sacred mountains, rivers, and cliffs.

Another exhibit gave information on the role of fetishes in Pueblo culture. These small, symbolic objects guide hunters, protect individuals and communities, promote healing, and bring rain and fertility to the land. Certain animals are associated with each of the directions: eagle for the sky, mole for the earth below, mountain lion in the north, badger in the south, wolf in the east, and bear in the west.

As we toured the center, I was especially interested to learn about the ways in which these traditional beliefs are intertwined with Catholicism.

The Franciscan fathers who came to this region in the 16th and 17th centuries chose a patron saint for each pueblo, one whose feast day coincided with the people’s existing traditional ceremonies. These saints continue to be honored during annual feast days at each pueblo. The celebrations include traditional dancing, singing, drumming, and feasting, along with a Catholic mass and processions through the streets. While these events are often open to the public, private ceremonies are still held in kivas (underground ceremonial chambers).

According to the center’s exhibits, many Puebloans believe that their adoption of the Catholic faith was not an unwelcome addition, but rather an enhancement of the spiritual traditions they had long followed. The contemporary Pueblos often view the two faiths as joined, linked by the common good of each and by a deep, prayerful connection.

Here’s a quote from one of the displays: “When asked why the Pueblos maintain Catholicism despite all of the hardship suffered under the Spanish, one Rio Grande Pueblo woman responded: ‘How old does something have to be before it’s your own traditional instead of ‘borrowed?” We’ve had the Catholic way for a long time; isn’t it our way by now?”

One of the ways in which the old traditions are kept alive is in native dances, which are held at the center each weekend. You can also have a meal at its Pueblo Harvest Cafe, which serves Native fusion cuisine that combines traditional Pueblo ingredients and flavors with contemporary cooking.

On our visit, I was very taken by the artwork on display, which included pottery, paintings, baskets, and jewelry. An artisans fair was being held in its central courtyard, and it was interesting to visit with the artists about their creations.

“Many of us incorporate spiritual symbols into our work,” a potter told me. “They may not be immediately obvious to others, but to us they have great meaning.”

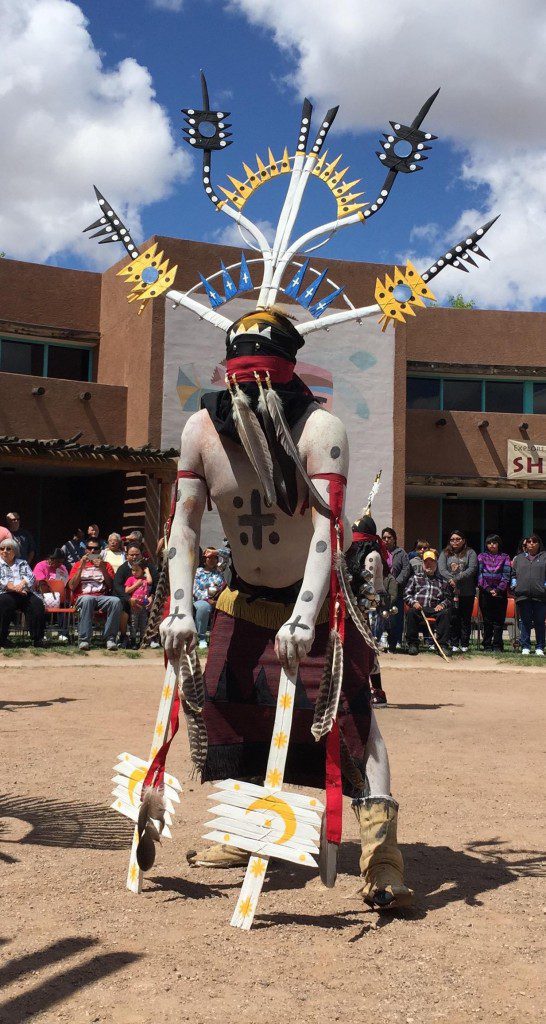

My most vivid memory of our visit is an extraordinary performance done by the White Mountain Apache Crown Dancers. There was a haunting quality to their dancing, in part because of their unusual costumes. As you can see from the photo above, the men’s faces were hidden by black cloths, making them look not quite human. White paint covered their bodies, contributing to the ghost-like element. As they danced, they seemed to be channeling something other-worldly.

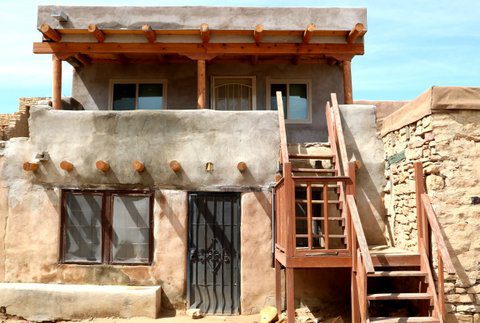

The second attraction we visited in the Albuquerque area was Acoma Pueblo Sky City, located 65 miles west of Albuquerque. Here we got the chance to see a place where the Puebloan culture is a living tradition.

The physical setting of the Acoma Pueblo is amazing: it is built atop a mesa nearly 370 feet above the desert floor.

After taking a bus up a steep hill to the top, we were led by a guide on a walking tour among the adobe and sandstone homes of the pueblo. People have been living at Acoma Pueblo since approximately 1100 A. D., making this one of the oldest continuously inhabited communities in North America. Our guide told us that for many centuries, the only way the pueblo could be reached was by a nearly vertical set of stairs cut into the rock.

After the Spaniards arrived, there was conflict and bloodshed, as well as diseases spread by the invaders. The rainwater basins on the mesa were contaminated by their horses and are unusable to this day.

Our guide, who had spent a good part of her childhood in the pueblo, explained that the homes are owned by Acoma Pueblo women. When an owner dies, the home is traditionally given to the youngest daughter of a family, as she is the one who is most likely to remain at home caring for the elders and keeping the cultural traditions alive.

Today the community has about 40 people who live here year-round, but additional relatives come for ceremonial occasions. The residents support themselves by selling handcrafts, including intricately detailed pottery.

Our tour ended at the San Esteban del Rey Mission, which was built between 1629-1640. After the Spaniards brought Christianity to this region of the country, mission churches like this one were built in each of the pueblos.

Our guide pointed out a hole in the fence that surrounds the church’s cemetery. “Several of our children were stolen by the Spaniards and taken away,” she said. “They never came back to us in life, but the gap in the fence was made so that their spirits could return here after death.”

I’ll long remember standing on that windswept plateau, a place where the spirits of many centuries seem to linger.

Stay in touch! Like Holy Rover on Facebook: