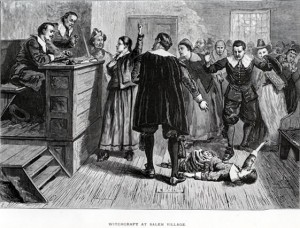

Before I visited Salem, I had a vague idea of what had happened there in 1692-3, but the full story is more complex than I had realized.

My understanding was largely formed by Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, which is set during the Witch Trials. But in Salem I was reminded that while The Crucible is a great play, it’s as much about the McCarthyism of the 1950s as it is about Salem. Miller used the broad outlines of the Witch Trials, but took liberties with the historical record to make his larger points about the climate of fear generated by Senator Joseph McCarthy.

What actually happened in Salem has its roots in the witch burnings of Europe. Beginning in the mid-fifteenth century and continuing for two centuries, many thousands of people were killed after being accused of witchcraft. Most were burned to death, some after undergoing ludicrous trials such as the “water test” (if you floated, you were a witch and were killed; if you sank, you were innocent but drowned). About three-quarters of those killed were women, often those who were poor and living on the margins of society. Most of the witch-burnings took place in Germany and England during times of civil war, religious strife, and plague. Finding a witch to blame was a way of dealing with terrible fears and tragedies.

What happened in Salem differed from the European pattern in some ways. No one was burned at Salem, for instance (nineteen of the accused were hanged, and one was crushed to death). Fourteen were women, and six were men. The trials also took place late in the witch hysteria period. In many ways the trials were the final chapter of a dying belief system, and the people who were killed in Salem were the last people to be executed for witchcraft in America. In fact, the trials led to such widespread revulsion that the word Puritan has negative connotations that continue to this day.

Salem in the late seventeenth-century was a vulnerable, struggling community trying to survive under harsh conditions. It was a society in which people took the supernatural very, very seriously, believing that the devil was constantly at work and that he was the cause of misfortunes such as illnesses, crop failures, and deaths. The community also had many tensions relating to property disputes, grazing rights, and church privileges. Salem, in short, was a fertile breeding ground for hysteria and fear.

Those making the accusations of witchcraft were a group of young girls ranging in age from nine to 19. They began to act strangely, screaming and throwing fits and uttering wild sounds. When questioned, they said they were being attacked by witches, naming various people in the community as the agents of the devil.

What possessed the girls to make these wild accusations? Surely there were many factors at work. Women, especially girls, had very little power or status in colonial America. It must have been an intoxicating experience for them to be listened to and feared. Some have speculated that perhaps the girls had eaten grain infected with a fungus that could cause hallucinations (though many think this is an unlikely thesis). Clearly there were great resentments in the larger community and many conflicts between neighbors over property and status. There were threats from the outside as well, as Indian attacks to the north were drawing increasingly close. And the religious theology of Puritanism–an honorable path in many ways–had been twisted into terribly unhealthy forms.

There was also simple mob psychology at work, too, as the young girls became a pack of bullies. They encouraged each other in evil, for evil is not too strong a word for what happened at Salem. Just as in Europe, their victims were at first the marginal members of the community–women whom people either disliked or feared for one reason or another. But eventually their net of accusation was cast wider and wider, drawing in widely respected people such as Martha Corey and Rebecca Nurse.

Most of the victims were convicted on the basis of “spectral evidence,” which consisted of the girls’ reports of demonic attacks that no one else could see. But in the trials, neighbors also testified against neighbors, bringing up past grievances as a way of getting revenge.

The nightmare finally ended when the girls began to accuse prominent and wealthy members of the community of witchcraft. That was a bridge too far, and the madness stopped when the governor ruled that “spectral evidence” could no longer be used in court.

The people of Salem would spend centuries living under the cloud of what had happened in their midst. Most of those involved with the trials later repented of what they had done, though some maintained to their deaths that they had acted honorably to fight the devil in Salem.

We’ll never know exactly what happened during this sad and tragic period, but surely we owe the victims this: we need to remember the injustice and brutality that befell them, and work to see that it does not happen again, in another time and under another guise.