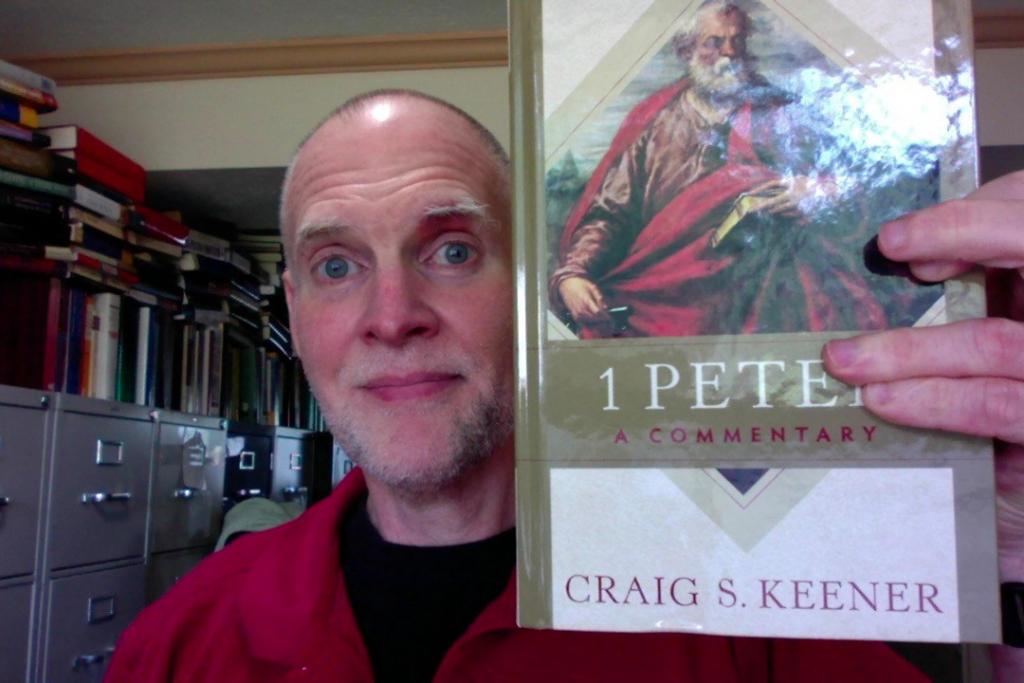

I had the privilege of recently interviewing biblical scholar and friend, Craig Keener,* on his new commentary, 1 Peter: A Commentary (Baker, 2021).

A blurb about this commentary reads as follows: “Leading New Testament scholar Craig Keener, one of the most trusted exegetes working today, is widely respected for his thorough research, sound judgments, and knowledge of ancient sources … This commentary on 1 Peter features Keener’s meticulous and comprehensive research and offers a wealth of fresh insights. It will benefit students, pastors, and church leaders alike.”

The Interview

B. J. Oropeza: Craig, it’s a pleasure to interview you on this important New Testament letter! Here’s my first question:

The recipients of 1 Peter are called foreigners and resident aliens (paroikous and parepidȇmous: 1 Peter 2:11). John Elliott, in his book A Home for the Homeless and his later works, asserts that these people were actually, rather than metaphorically, socially marginalized. Do you agree with him? How would you identify these Christians?

Craig Keener: I think that most of them probably were socially marginalized, but I don’t think that’s what Peter meant by the terms paroikous and parepidȇmous. I think that in the face of the impending persecution that he expected for their faith, he wanted them to remember that this present world design is not their home. They would understand this because these terms were already widely used in figurative senses in antiquity, including in Diaspora Jewish writers such as Philo.

Thus, in 2:11 Peter urges his audience as foreigners and strangers to abstain from fleshly passions that war against the soul. (The danger of citing that verse is that it opens an entirely different can of worms of its own, but I will try to stay on track here!) For the gospel’s sake, Peter wants his audience, a marginal minority, to continue to submit to the strictures of the world as best they can. This includes submission to kings (1 Pet 2:13), to slaveholders (2:18), to male householders (3:1). But he explicitly regards these as human institutions (2:13), comparing this situation with Christ’s suffering at the world’s hands (2:21-25). These are not God’s institutions or meant to mandate such institutions for all cultures and times.

B. J.: Regarding submission to these ancient institutes, whether to kings, masters, or male householders/ husbands, how is such instruction relevant for Christians today?

Craig: They might give us pause in our sometimes loud U.S. individualistic rights type of thinking. Christians today are not the kind of vulnerable minority that Peter’s audience was, and most of us in the West live in societies where we are free to share our perspectives. But we are not the majority, and we still need to approach nonbelievers respectfully and graciously. And that being the case, it should go without saying that we should approach fellow believers respectfully and graciously too.

The stereotype of angry Christians shouting people down is not one inculcated by Jesus or advised by Peter. We are here to serve, whatever our given roles are in society. This isn’t saying that our roles cannot change. It’s not saying, for example, that we need to reinstitute the monarchy so that we could obey Peter’s injunction to honor the king. But whatever our roles happen to be, we silence the slanders against us not by retaliating (and polarizing the rhetoric further, as U. S. politics often does), but by loving and serving insofar as is possible and physically safe.

B. J.: Suffering appears to be a type of confirmation related to being called “Christian” (Christianos) in 1 Peter 4:12-19. Apart from the Book of Acts 11:26 and 26:28, this is the only other source in the New Testament that uses the term. When did Christ-followers first begin to be called “Christians,” and when did this term become the norm for identifying Christ followers? Also, what is its significance?

Craig: Suffering, and how to face suffering, is a key issue throughout 1 Peter. Acts 11 says that disciples of Jesus were first called Christians in Antioch, a city known for giving groups nicknames. The “-ian” suffix normally identified political partisans—Caesarians, Herodians, and so on. “Christians,” then, were viewed as partisans of the Christ (the king). It was a term of derision or at least taunting. In 1 Peter 4, it functions virtually as a legal charge. By the second century, Jesus followers had embraced the term as a badge of honor, but initially it was not intended by its speakers so benignly.

B. J.: In 1 Peter 5:8–10 Satan is described as a roaring lion seeking whom he may devour or swallow up (katapino). In what sense would he “devour” believers? I have suggested this is referring to the possibility of believers falling away (apostasy) in Churches under Siege of Persecution and Assimilation: The General Epistles and Revelation. What is your interpretation of this text?

Craig: I also believe that this refers to Satan seeking to make God’s people fall away, especially through persecution in the case of 1 Peter. The lion image fits well with the preceding image of shepherds and the flock. We are not called to resist the world with violence or harshness, but we are called to resist Satan’s devouring, to stand firm no matter what tests we must face.

B. J.: There are scholars who think the Greek in 1 Peter is too good to be written by Peter the apostle, a simple Galilean fisherman according to tradition. However, both Silvanus (Silas) and Mark are mentioned towards the ending of the letter. Do you think either of them were involved in the letter’s composition? What is your view of the authorship of this letter?

Craig: The Greek probably is too good for Peter. Peter would not have to write the letter, of course. Wealthy persons dictated to scribes what to write because they could, and illiterate persons depended on scribes because they had to. Also, being from Lower Galilee and having spent years in Jerusalem, Peter would undoubtedly be able to converse in Greek and could probably preach in the language. But even allowing for dictation, the Greek of 1 Peter is of higher quality than Peter would probably muster on his own. We should keep in mind, however, that by the 60s CE, Peter has been a leading figure in the Jesus movement for quite some time. As Jesus’s chief disciple he would have plenty of people eager to help him with dialoguing and wordsmithing.

As to whether Silvanus or Mark or both could have helped—Silvanus, for example, may have contributed to some of Paul’s letters (depending on what is meant in 2 Cor 1:19; 1 Thess 1:1; and I believe also 2 Thess 1:1). Many scholars today argue that Peter writing “through” Silvanus (1 Pet 5:12) simply means that he sent the letter by Silvanus, not that Silvanus literally helped him write it. They argue that the Greek phrase “write through” always means this. While the Greek phrase sometimes means this, it is by no means the case that it always does. I and one of my PhD students surveyed the usage in the papyri and found examples where it actually does entail the person’s aid in writing.

As for Mark—within living memory of the writing of Mark’s Gospel, the church father Papias says that he heard directly from people who knew the first apostles that Mark wrote down what he recalled of Peter’s often recounted memories of Jesus. Many scholars are skeptical of these claims, but I do not see reason to dismiss explicit evidence even stronger than much of that on which classicists often depend for their attributions of authorship. Plus, we have 1 Peter widely used as authoritative in early second century fathers, a use they would surely have avoided had they considered the authorship claim (1 Pet 1:1) pseudonymous. So I do think Peter had help, and I do see 1 Pet 5:12-13 as pointing in that direction. But I do think that we have in this letter the voice and heart of Peter, Jesus’s own disciple.

B. J.: I’m noticing that scholars today are generally placing more value on evidence and teachings from the early church writers than they did about a generation ago. That, I think, is a healthy trend. One final question—what do you consider to be one of the most important takeaways for people today to learn, believe, or practice when reading 1 Peter?

Craig: We each have different kinds of testing, not always the same that Peter’s first audience faced. But we are called to persevere and to be lights for Christ in this world. 1 Peter provides us the theological resources to empower us to stand firm—Christ our deliverer, Christ our model, the way that God has consecrated and rebirthed us by the Spirit, and so on.

This letter also provides us with reminders on how we should respond to those who mistreat us. I’m not saying that an abused spouse should remain in an abusive situation. I’m speaking generally; and many of us, like most first-century slaves, are in situations from which we cannot extricate ourselves. I have been beaten and had my life threatened before for sharing my faith. Whatever the situation might be in which we face hostility—whether for our marginal status in other ways or because we follow Jesus—we seek to win people over by acting toward them like Christ modeled for us in laying down his life.

We do seek to set the record straight by speaking truth, but most of all we seek to show Jesus’s heart by love. All of this is an important reminder in our divided country and world right now.

B. J.: A very appropriate message for our times. Craig, it’s always pleasure talking with you. Good luck and I wish you much success with this new book!

Notes

* Craig Keener’s bio reads as follows: “Craig Keener (PhD, Duke University) is professor of New Testament at Asbury Theological Seminary. Six of his many books have won national awards, and his books together have sold more than one million copies. His books include heavily academic works (such as his four-volume Acts commentary) and popular ones (such as The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament). He has published roughly one hundred academic articles and more than one hundred fifty popular-level articles. Craig is married to Dr. Medine Moussounga Keener, who holds a Ph.D. from University of Paris. She was a refugee for 18 months in her nation of Congo; their story appears in Impossible Love.”

Image: Craig Keener’s self portrait, approved by Keener