The great 13th century Dominican philosopher Thomas Aquinas writes about Jacob’s election over Esau prior to either son being born. God made his choice before either child could do anything good or bad (Romans 9:10–12/ Genesis 25:21–25). According to Aquinas’s Commentary on Romans (C.9 L.2.758), this passage excludes at least three errors:

First, it precludes assumptions that one can trust in the merits of one’s ancestors. In other words, God is not obligated to excuse individuals purely because of the good deeds of their parents. (In biblical times, for example, an immoral person is not excused from divine punishment simply because he or she is a child of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.)

First, it precludes assumptions that one can trust in the merits of one’s ancestors. In other words, God is not obligated to excuse individuals purely because of the good deeds of their parents. (In biblical times, for example, an immoral person is not excused from divine punishment simply because he or she is a child of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.)- Second, it excludes the Manichean claims that the constellation under which a human is born controls that person’s life and death. (In contemporary terms, horoscope teachers are refuted.)

- Third, it refutes the Pelagian misconception that a person’s merits precede rather than follow from grace. Aquinas adds to this point Titus 3:5, which states that God saves us according to his own justice and mercy rather than by any works we have done.

When discussing God’s claim, “Jacob I loved, Esau I hated” (Romans 9:13 in Commentary on Romans, C9 L.2.764, 771), Aquinas asserts that foreknowledge of merits is not the reason for predestination. Rather, foreknown merits are to be placed “under predestination” (sub praedestinatione). This means basically that God does not bestow grace due to earlier human merits; rather, merits themselves are a gift from God effected from predestination.

On the other hand, Aquinas affirms that God can have foreknowledge of sin, and sin is the reason for punishment and reprobation (condemnation). Humans do not sin due to God but due to their own selves. (In other words, God does not predestine that individuals sin.)

We see in these words that Aquinas affirms a strong view of predestination, but at the same time he rejects double predestination in which both the saved and damned are pre-determined by God.

Discussing God’s declaration, “I will have mercy on whom I will have mercy” (Romans 9:14-15 in C.9 L.3.773), Aquinas provides an illustration on why the claim is not unjust:

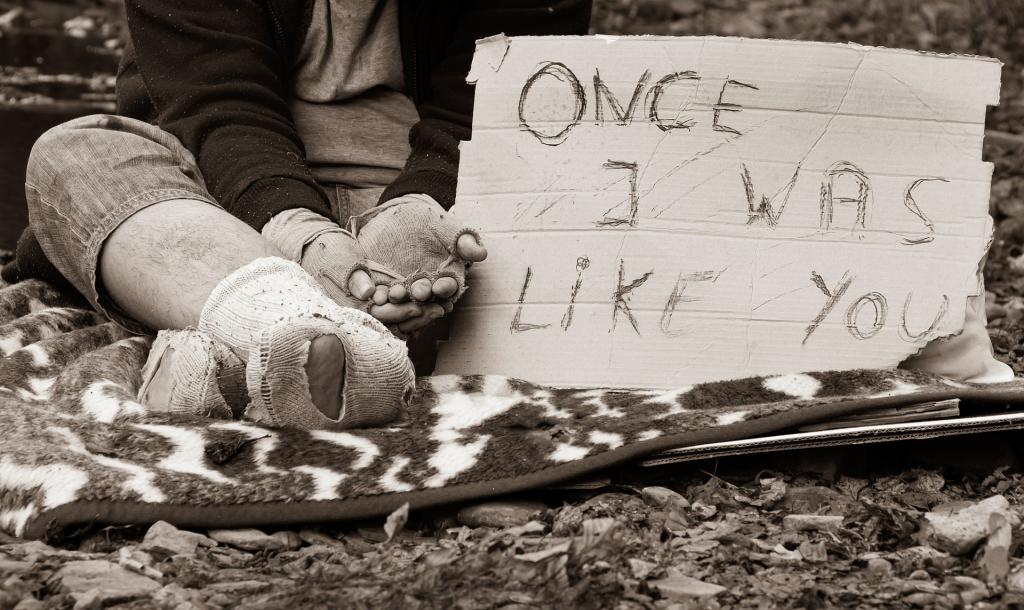

“If a person meets two beggars and gives one an alms, he is not unjust but merciful. Similarly, if a person has been offended equally by two people and he forgives one but not the other, he is merciful to the one, just to the other, but unjust to neither.”[1]

Here Aquinas agrees with St. Augustine that all humans are born subject to sin and guilt due to Adam and Eve’s sin. Hence, for God to show mercy to anyone is an act of grace with no injustice to those who do not receive mercy. Why? Because the normal outcome of justice is that all sinners should be punished.

Aquinas explains the notion of God hardening whomever he wills (Romans 9:18 in C.9 L.3.784) not as a direct but an indirect activity. That is because God never infuses malice; humans themselves do malice because of their own sinfulness. What God does in such hardening is that he simply withholds grace.

Reflections on Aquinas and Mercy in Romans 9

In this instalment of the Romans 9 debate, it is clear that Aquinas was influenced by St. Augustine’s view of original sin and predestination. Augustine’s view was generally accepted in the western churches throughout the Middle Ages.

Aquinas’s illustrations that attempt to explain God’s grace, mercy, and justice prompt our desire to want further explanation. In relation to the two beggars, what Aquinas does not mention is that human generosity has limits based on the amount of goods one might have.

Let us suppose that a hundred homeless people came to you and all asked for alms. You might be able give something to a number of them, but eventually you will run out of goods to give. If you have one final plate of food left, the choice of who to give it to will probably depend on which person was next in line to receive a plate, or which one has the greatest need, or who is crying out the most earnestly, or which person you might know personally. If you are like most people, then, you will try to be fair even with your last handout. Or, you will have what you consider to be a good reason to give the plate to person X rather than person Y.

God, however, has unlimited resources. There is no reason, then, conceivably speaking, why God could not be gracious to everyone. If God withholds grace from some, we suspect he has a good reason for doing so. Aquinas’s illustration, then, may be correct in saying that the person is merciful for giving alms to one and not the other, but he leaves out whether there was any reason behind the choice. Is the choice purely arbitrary and thus God’s choice also arbitrary? Does it not make more sense to suggest that there is a good purpose behind the choices that are made?

Aquinas’s second illustration about forgiving one and not the other also leaves too much unsaid. As Christians are we not commanded to forgive all who wrong us, as Jesus teaches (Matthew 6:14–15)? Though on a corporate level, such as a crime against the State, the issue of offense and pardon may be handled in a way similar to what Aquinas is saying.

In the U.S., a president can pardon one criminal and not the other who commits a similar crime. This happens all the time. However, that president does not pardon whimsically. In recent memory (i.e., with Bush, Obama, Trump), things such as circumstances behind the crime, the person’s changed behavior since the crime, communicating with that person personally, or some political reason, help them determine their choices. In other words, they do not pardon arbitrarily. They have a purpose behind selecting who they decide to pardon, regardless of whether the public agrees with those choices or not.

So once again, with the second illustration, Aquinas is silent on the reason behind the choice of forgiving one and not the other. Since foreknowledge is under the rubric of predestination according to Aquinas, did God “shut off” his omniscience and foreknowledge, as it were, when first choosing to be gracious to some? I suppose that my interlocutors might respond that this is a “mystery,” while others might suggest that God does not know all future events (Open Theism). But these are not the type of answers the patristic theologians gave during the first few centuries of the Christian faith prior to Augustine.

Aquinas aside, what do Medieval and Reformation theologians think about Romans 9? Stay tuned!

Notes

[1] Translation by F. R. Larcher in Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on the Letter of Saint Paul to the Romans (Lander, WY: The Aquinas Institute for the Study of Sacred Doctrine, 2012), 259.Image 1: Stained glass window church dove holy via pixabay.com; Image 2: homeless man beggar poverty begging alms via pixabay.com