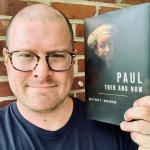

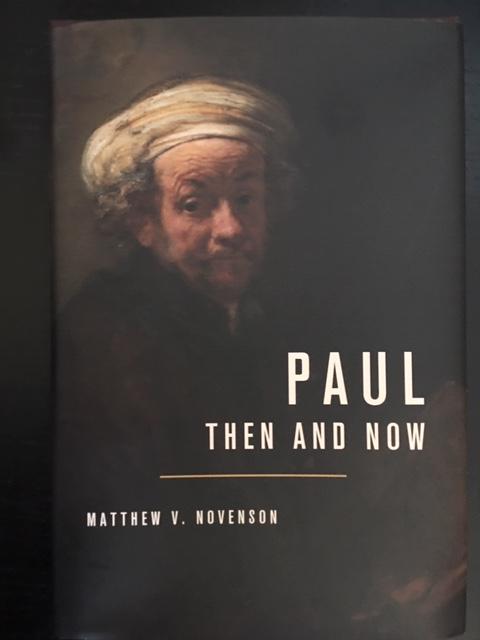

I had to privilege of reviewing the new book by Matthew V. Novenson, entitled Paul, Then and Now (Eerdmans, 2022). Dr. Novenson is Senior Lecturer in New Testament and Christian Origins at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. He has written a number of articles and books including the monograph, Christ among Messiahs: Christ Language in Paul and Messiah Language in Ancient Judaism (Oxford University Press) and co-edited the massive Oxford Handbook on Pauline Studies.

On the book’s back cover, Prof. John Barclay says of Dr. Novenson that he “has emerged as a leading Pauline scholar,” and his current collection of essays is an example of this. Dr. Novenson is a leading advocate for the continued relevance of the historical method in relation to Paul. He brings Paul’s letter into conversation with Christian reception history. Even so, his interpretation of Paul is anything but traditional!

In this first instalment, I provide an overview of Paul, Then and Now. The instalments after this will cover an actual interview with Dr. Novenson about his book.

Book Review

Chapter 1

Novenson’s opening chapter targets how interpreters of Paul in the “now” often read him in a way that accommodates their own thinking. We “normalize” Paul. This is comparable with Albert Schweitzer’s famous claim over a hundred years ago that the studies of the historical Jesus amount to interpreters looking down a well and simply seeing a reflection of themselves. Our discovering of the Paul back “then” may result in discovering an apostle who is quite different than our normalizations of him. He could turn out to be quite “weird,” and that should be okay with us.

Chapter 2

The next chapter focuses on Romans 1–2 in relation to theology and historical criticism. Novenson uncovers that today we have two distinct senses of Paul’s theology—Paul’s own theology and the interpreter’s theology of Paul. Here again we see a difference between Paul “then” and Paul “now.” What I received from this chapter is that we should be aware that Paul’s own theology may be different from our own. Our own theology has been colored by almost 2,000 years of church and theological history (not to mention our denominational upbringing). To be aware of this dichotomy makes for a complex reading of Paul, and, for Novenson, that is perfectly fine.

Chapters 3 and 4

In chapter three, Novenson tackles the issue of how Paul’s thought is characterized as Jewish (Ἰουδαῖος) and as a Pharisee. This chapter also addresses zealots. Novenson emphasizes the Jewishness of Paul who “was a Ἰουδαῖος of the diaspora who preferred to style himself a Hebrew, Israelite, or Benjamite” (45). A refreshing thing I noticed about Novensen’s chapters is that he is thoroughly up-to-date when it comes to engaging with what scholars are saying today about these issues, rather than 20 years ago.

In a similar vein, he addresses in chapter four the question of whether Paul ever abandoned Judaism or monotheism. This chapter I found particular stimulating as he covers the most relevant passages that address these issues, including the question of why Paul was persecuted, his becoming all things to all people (1 Cor 9:19–22), the “many gods and many lords” passage in 1 Cor 8:4–6. In these and other texts, Novenson provides his own fresh and challenging interpretation. For Novenson, Paul did not abandon Judaism, and “monotheism” turns out to be a problematic term. In any case, Paul believed like others Jews that devotion should be to the one God, though Paul also speaks of the one Lord Jesus Christ.

Chapter 5

Chapter five provides an overview of Romans and Galatians, the two letters that are almost a canon within a canon for Protestant churches. In Galatians 6:2 Novenson interprets the “law of Christ” as arguably best understood “as the law, God’s law, which now, in the messianic age, can be done fully and effortlessly by those who have the pneuma [Spirit]” (73). From Romans, among other things, we learn that the divided person who does what he hates doing in Romans 7 points to “a hypothetical gentile auditor who tries to attain righteousness by following the law.” Such a person “will find herself endlessly frustrated, because in the present evil age, even the law itself is at the mercy of sin and the passions” (79).

Chapters 6, 7, 8

The next chapter covers the “self-styled” Jew in Romans 2 and the plight of Israel in Romans 9–11. Similar to Runar Thorsteinsson and others, Novenson believes the “Jew” in Rom 2:17 is really a gentile playing a Jew.[1] In chapter seven he responds to criticisms of his previous book, Christ among Messiahs. In chapter eight he addresses Paul’s “God as Witness” sayings (e.g., Rom 1:9; 2 Cor 1:23; Phil 1:8) in light of Greco-Roman rhetoric. When the apostle’s moral intention is called into question, like Aristotle, Demosthenes, Philo, and Josephus, he makes such an appeal to God. “In such appeals, Paul is not swearing anything; rather he is inviting God to swear concerning him” (143).

Chapter 9, 10, 11

Against quite a few recent interpreters, Novenson in chapter nine contests that Paul’s view of gentiles is influenced by the end-time pilgrimage of the nations to Zion. (Such a view is found in prophecies such as Isaiah 2, 25, 56, 66, Micah 4, and Zechariah 8.) Novenson’s interpretation affects the way we read passages such as Romans 11 and 15 where gentiles come to the foreground. Chapter ten engages with the recent works of Paul Fredriksen (Paul, the Pagan’s Apostle) and John Gager (Who Made Early Christianity? The Jewish Lives of the Apostle Paul). And chapter eleven focuses on the way the church father Tertullian reads Paul.

Finally in chapter twelve, Novenson returns again to the topic of how interpreters read Paul, then and now. This time, he focuses on the problem of Anti-Judaism in traditional Protestant interpretation.

* * *

In our next instalments, I will interview Dr. Novenson about his book. So stay tuned…

Notes

[1] For my own interpretation of Thorsteinsson’s view in Paul’s Interlocutor in Romans (Almqvist & Wiksell), see my article, “Is the Jew in Romans 2:17 Really a Gentile?” Academia Letters (2021) 1–4.