I suppose I’m sort of an insider to questions on which Bible a person should use. That is because I had the privilege of working on Bible translations as diverse as the Common English Bible, the New Revised Standard Version (updated edition), and the Lexham English Septuagint. I also worked on the Wesley Study Bible and recently on the HarperCollins Study Bible (updated edition). And as Professor of Biblical Studies at Azusa Pacific University—a mostly Wesleyan institute that claims an evangelical heritage—I suppose I could field questions about evangelicals, too.

So here is my conclusion upfront regarding which Bible evangelicals use. There is no Bible that stands out today as the most authoritative one for evangelicals.

I can say this without hesitation because, inter alia, evangelicals are quite a diverse group. On our campus at APU (though certainly not only on APU’s campus) we have “conservative,” “progressive,” and even some “post-” evangelicals. We welcome dispensational, non-denominational, charismatic, and Pentecostal evangelicals alike; not to mention, we even welcome students who claim no form of evangelicalism at all.

If I were to ask the question, “What’s your favorite Bible?” to any five students on campus—that is, students who actually own a Bible rather than simply read whichever version pops up first on their smart phone—I would probably get six different answers!

Even so, if we look back at previous generations of evangelicals, we do find that there is perhaps a preferred Bible version and study Bible.

The Bible Used Back Then

The King James Version has left its indubitable mark on evangelicals in generations past. But that should not be surprising. American Christians of almost every stripe, and indeed American culture itself, has been shaped by this translation. We are better off understanding the evangelical heritage by pointing to a particular study Bible that has influenced millions.

That study Bible is the Scofield Reference Bible, which came out a little over a hundred years ago and influenced entire generations of evangelicals. Its influence is still felt today. This Bible promoted dispensationalism, a theological perspective that reads prophecy and the Book of Revelation quite literally. It interprets the seven churches addressed in Revelation as seven eras or dispensations that are to take place before Christ returns. This view received further impetus through the writings of Hal Lindsey in the 1970’s and 1980’s (e.g., The Late Great Planet Earth), and through Tim LaHaye’s Left Behind series at the turn of the Millennium.

To this day Scofield’s legacy lives on (frustratingly, in my estimation). A number of evangelical parishioners still take it for granted that there will be a rapture of the church before seven years of the “great tribulation” in which the Anti-Christ will start to rule and force everyone to take the mark of the Beast (666). Then the Second Coming happens (or is it a third coming given that the rapture was the second?). After that, a literal 1,000 year reign of Christ takes place on earth. Never mind that we search in vain for any one passage in the Bible that clearly tells us a rapture will take place seven years before Christ returns. Never mind that Revelation is apocalyptic literature, which is full of symbols (In heaven will we see Christ as a literal lamb with seven eyes?).

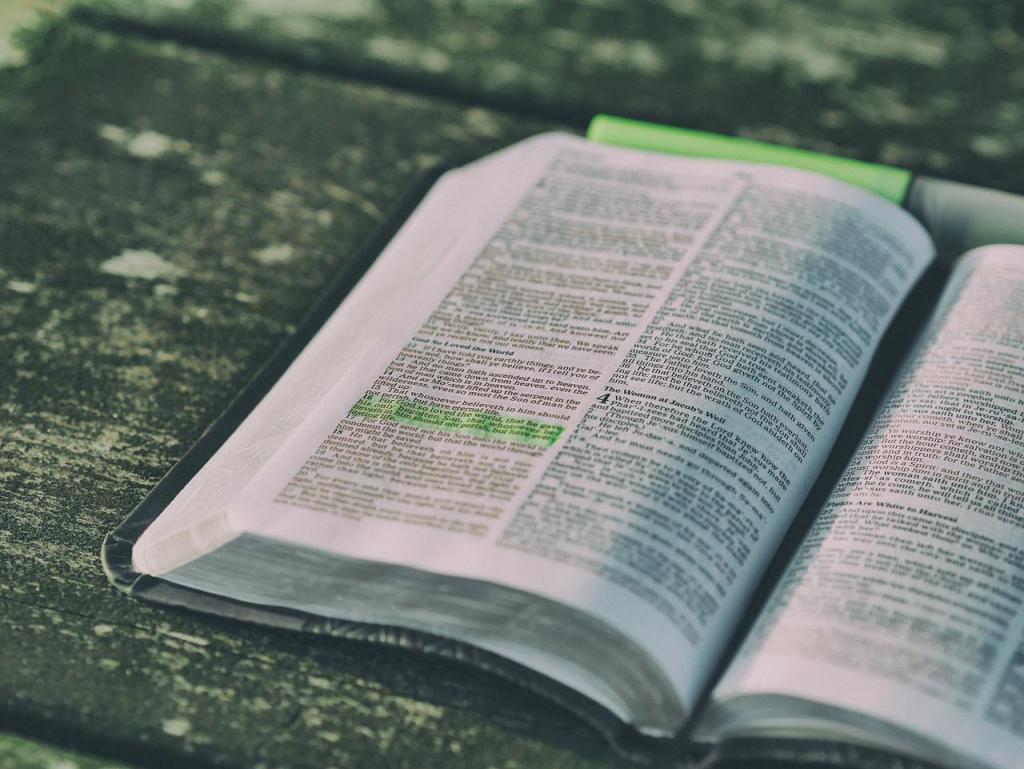

The Bibles Used Now

In more recent decades, the Scofield Reference Bible has lost the corner market when it comes to Bibles that evangelicals use. The Thompson Chain Reference Bible has always been a competitor, and then in the 1980’s, the NIV Study Bible started taking evangelicals by storm. As early as the 1970’s, the paraphrased TLB (The Living Bible, or simply LB) and the NIV (New International Version) translations likewise stole converts from the KJV. The NIV translation was spearheaded by the Christian Reformed Church and the National Association of Evangelicals. Kenneth N. Taylor, an evangelical, produced the TLB.

Today, there are too many study Bibles to mention. We only scratch the surface when pointing out the ESV Study Bible, the Reformation Study Bible, the Wesley Study Bible, the Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible, the New Spirit-Filled Life Study Bible, the HarperCollins Study Bible, the ESV Women’s Study Bible, and our own university’s standard requisite—the more ecumenical than evangelical New Oxford Annotated Bible (NOAB).

When it comes to study Bibles, conservative evangelicals will probably like the ESV Study Bible, ecumenists NOAB, and progressives HarperCollins. But study Bibles are mostly too shallow for me. Any serious reader of Scripture will want to consult the numerous commentary sets that are out there. (And I don’t mean Matthew Henry, an outdated favorite of past generations.) The sets include the New International Commentary (Eerdmans), Word Biblical Commentary (Zondervan), Baker Exegetical Commentary, the more user-friendly New Covenant Commentary (Cascade), and The Story God Bible Commentary (Zondervan), just to name a few. To find out what Luther, Calvin, Augustine, John Chrysostom, Origen, and many other past greats say, there’s the Reformation Commentary on Scripture and the Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, both from IVP. Any of these are normally way more thorough than a study Bible.

Are There Any Preferences among Evangelicals When it Comes to Bible Translations?

Updated versions of the NIV (TNIV) and TLB (NLT) are still popular among evangelicals, as is the English Standard Version. The ESV has the aim of being an “essentially literal” translation, as the Preface states, and members of the oversight committee are scholars from evangelical institutes. The Holman Christian Standard Bible (HSCB), and now CSB, is also picking up steam. The translators here are committed to biblical inerrancy. That may impress conservative evangelicals.

All the same, I would recommend the more literal translations since this way the reader is getting closer to what the Greek and Hebrew says. Hence, the ESV and CSB are more preferable than the “dynamic equivalence” translations of the NIV and TNIV, and much more preferable than paraphrased versions such as TLB, NLT, and The Message.

Let’s take one example comparing the ESV and NIV. In Galatians 5:16, the ESV follows the Greek fairly well: “But I say, walk by the Spirit, and you will not gratify the desires of the flesh.” But the NIV has, “So I say, live by the Spirit, and you will not gratify the desires of the sinful nature.” The Greek does not say “live” nor “sinful nature.” This translation, among other things, overlooks the importance of the metaphor of walking as a way of behaving rightly. Any Jewish interpreter of Moses’ law would recognize this importance, since Halakha (“the way of walking”) refers to laws derived from the oral and written Torah. Paul is implying that believers in Christ are to “walk” in the ways of the Holy Spirit rather than in the works of the Torah. This important implication for the Galatians is missed in the NIV.

My Own Preferences

As a reader of the original languages, my choices for translations that try to follow the Greek and Hebrew include the Lexham English Bible (LEB), New American Standard Bible (NASB), New English Translation (NET), and ESV. I also like to compare my own translations sometimes with Young’s Literal Translation (19th c.). It translates texts awkwardly, however, attempting to be literal at almost any cost.

The NKJV is a literal translation that jumps the hurdle of its predecessor’s Shakespearian English, but it still relies on inferior manuscripts of the original languages. Here is one example among many: from Romans 1:16, the NKJV has “I am not ashamed of the gospel of Christ.” But older Greek manuscripts, unavailable to translators in 1611, do not have “of Christ” (such as Codex Sinaiticus, Codex Vaticanus, Papyrus 26, etc.). The shorter version is likely the more original; there is no compelling reason why copyists would omit the sacred name of Christ if it were originally there. Most modern versions correctly have the shorter reading, unlike NKJV.

The NRSV, though great in its use of inclusive language, also suffers setbacks for this very reason. For example, in 1 Corinthians 10:12, an adequate translation from the Greek is, “The one who thinks he stands, let him take heed, lest he fall.” However, to avoid “he” and “him,” the NRSV renders the verse differently: “So if you think you are standing, watch out that you do not fall.” There is a problem here—the Greek uses third person singulars, not the second person “you.” Also, this translation does not tell us whether it’s a singular or plural “you,” important for how Paul is distinguishing a collective group from factions in this context. The NRSV is thus not as literal as the other versions I mentioned.

Conclusions

Evangelicals have come a long way since the KJV and Scofield Reference Bible. I think it is a good thing that a growing number of them are choosing different translations and study Bibles these days. Despite my reluctance to boil down this article to the best Bible for evangelicals, I do know what the worst Bible is: it’s the Bible that is never read.