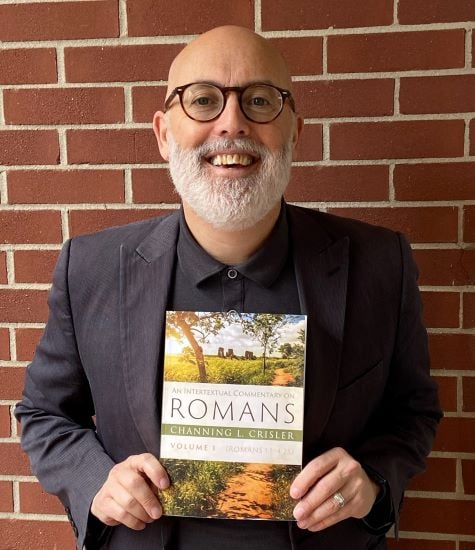

I recently had the privilege of interviewing Channing Crisler on his current multi-volume work, An Intertextual Commentary on Romans (Pickwick Publications). Dr. Channing has written three volumes thus far—the first on Romans 1:1–4:25, the second on Romans 5:1–8:39, and third on Romans 9:1–11:36. This post will cover his first volume.

Dr. Channing L. Crisler is Associate Professor of New Testament at Anderson University, South Carolina. He has authored Reading Romans as Lament (Pickwick); Echoes of Lament in the Christology of Luke’s Gospel (Sheffield Phoenix Press); and co-authored Always Reforming: Reflections on Martin Luther and Biblical Studies (Lexham Press), and The Bible Toolbox (B&H Academic).

A unique aspect about this commentary on Romans is that it centers on exploring intertextuality, the presence of a text in another text. In biblical studies, intertextuality includes the study of New Testament use of Jewish Scripture, such as the Hebrew (Masoretic) Old Testament and Greek Old Testament (Septuagint/LXX). It can also include biblical use of non-biblical traditions, whether from Hellenistic or Roman literature, ancient inscriptions, numismatics (coins), or other media forms.

For years, I have promoted the importance of intertextuality for Bible interpretation, both in my own publications (click here for an example) and for Patheos (click here for an example). And so it is refreshing to see this approach used as a commentary on Romans, a letter that cites and alludes to Jewish Scripture more than any of his other letters.

And now, here’s the interview:

An Intertextual Commentary on Romans: Volume 1 (Romans 1:1–4:25)

B. J. Oropeza

You feature intertextuality in this commentary set. What is your approach to intertextuality?

Channing Crisler

This is an important and fundamental question to any intertextual study, especially a study of Paul’s letters. My overall approach to intertextuality can largely be defined as a version of metalepsis. In its broad, ancient Greco-Roman sense, metalepsis simply referred to “the use of one word for another.” However, within the field of biblical studies, especially since the seminal work of Richard Hays, metalepsis refers to the conceptual effect produced by the interplay between two texts.

In my commentary, I employ the terms pre-text and text to distinguish an Old Testament text (pre-text) and Romans (text). When Romans contains a citation, allusion, or echo of the Old Testament, that pre-text(s) informs the meaning of Paul’s text on a narrative and/or rhetorical level.

Narratively, Paul’s use of the Old Testament (OT) in Romans often evokes larger narrative strands related to seminal moments, figures, and the like from Israel’s heritage. Therefore, his OT uses must be read in relation to these larger strands.

Rhetorically, so much of Paul’s vocabulary, theological idiom, and modes of communication are shaped by his engagement with specific pre-texts. Overall, a metaleptic approach articulates what is left unstated but assumed, or implied, by the interplay between Paul’s OT pre-text and the text of his letter.

B. J. Oropeza

How does a person determine that an allusion (or echo) of the Old Testament or another source is present through Paul’s words?

Channing Crisler

Determining the presence of this interplay can prove challenging. In the commentary, I focus on three broad kinds of intertextual engagement: (1) citations; (2) allusions; and (3) echoes.

Citations are, of course, the easiest kind of OT usage to identify since they are often marked by citation formulas or pauses within the flow of Paul’s thought (for example, a marked citation formula Paul often uses is: “As it is written”…).

I define allusions as explicit references to OT figures, events, and the like without an explicit citation of the said pre-text. Paul’s reference to Adam is a clear example of allusion. While he clearly engages Genesis 3 in Romans 5:12–21, Paul never cites a single line from that narrative. Therefore, one determines the presence of an allusion by an explicit reference to an OT entity which lacks an explicit citation of the pre-text from which it originates.

Finally, it is the intertextual echo that proves most difficult to verify. This aural metaphor, made popular in Pauline interpretation by Richard Hays, refers to the presence of a singular clause or string of words that evoke a wider OT pre-text. In the commentary, I generally require a proposed echo in Romans to match at least three terms, not including conjunctions, in its OT pre-text. Exceptions to the three-term requirement include Paul’s use of rare OT terms such as ἱλαστήριον in Rom 3:25 (translated as “mercy seat” by NET; “sacrifice of atonement” by NRSV). This echoes Exodus 25 and Leviticus 16.

B. J. Oropeza

The importance of Romans 1:16-17 as the thesis of Romans should not be overlooked; it influences the entire letter: “For I am not ashamed of the gospel, for it is God’s power for salvation to everyone who believes, both to Jew first and Greek. For in it God’s righteousness is being revealed from faith to faith, just as it is written: ‘but the righteous by faith shall live.’”

What type of citations, allusions, or echoes do you find in Rom 1:16-17? Could you share with us some more unique insights you discovered when unearthing the intertext of these verses?

Channing Crisler

While consensus among scholars can be rare, most interpreters identify Rom 1:16–17 as the thesis/propositio of the letter. Therefore, intertextually, no two verses are more important for understanding the impact of Israel’s Scriptures on the entirety of Paul’s argument. In Volume 1 of the commentary, I discuss at length the intertextual layers embedded in Paul’s thesis. I will highlight four of those intertextual insights here:

-

Paul’s Use of “Ashamed” in Romans 1:16

Paul’s use of ἐπαισχύνομαι (“I am [not] ashamed”) in Rom 1:16 echoes the ἀισχυν–root from the Greek Psalms, particularly the Psalms of Lament. Speakers in the psalms often wrestle with potential disappointment with God’s prior promises given the suffering they face from several sources such as geopolitical enemies, enemies within the community of God, ongoing struggles with sin, and intangible inimical forces, and what this suffering says about God’s judgment/wrath against his people.

In this tension between God’s promise of salvation and the lamenters’ pain, cries arise asking that God not disappoint them by failing to carry through with his promise, an outcome which would lead the psalmist to be ashamed of proclaiming his trust in Israel’s God (see, e.g., Pss LXX 21:5–6; 24:2).

Similarly, in Romans, Paul writes to a community suffering from ongoing problems with sin (Rom 6–7), worries about inimical forces that threaten to separate believers from God’s love in Christ (Rom 8), questions about Israel’s unbelief in its own Messiah (Rom 9–11), internal conflicts between the weak and strong in faith (Rom 14), and perhaps some problems with false teachers and/or Satan’s work in the community (Rom 16:17–20).

What encases these troubles is an overarching concern with divine wrath (Rom 1:18–3:20). How should the Romans understand their ongoing struggles given the fact that they live in a world under God’s wrath? In other words, the situation of the Romans parallels what we find in the Psalms of Lament.

Consequently, in Paul’s thesis statement, he encourages the Romans by noting that he himself is not “disappointed-ashamed” with the gospel because, despite afflictions that might imply the contrary, it is the power of God resulting in salvation.

Against this intertextual backdrop, ἐπαισχύνομαι in Rom 1:16 is not a mere reference to embarrassment which stems from speaking publicly about a crucified and risen Christ. Rather, in keeping with the ethos of the Psalms of Lament—and in response to what ails the Roman community—Paul is not disappointed in what the gospel promises, afflictions notwithstanding. It is a controlling motif that he calls back at various points in the letter through the ἀισχυν–root (e.g., Rom 5:5; 9:33; 10:11).

-

Paul’s Use of Psalm 98 in Romans 1:16–17

Another intertextual layer in Romans 1:16–17 involves Psalm 98 (97 LXX), as many interpreters note. What particularly stands out is Paul’s reference to the revelation of God’s righteousness (δικαιοσύνη θεου) in v. 17 which echoes Ps 97:2 LXX, “The Lord made known his salvation, he revealed his righteousness (ἀπεκάλυψεν τὴν δικαιοσύνην αὐτοῦ) before the nations.”

The much-debated referent of δικαιοσύνη θεου in Rom 1:17 is largely shaped by Paul’s engagement with the fuller context of this psalm. The wider context evokes motifs that Paul engages throughout the letter:

(1) saving righteousness as indicated through the parallelism in Ps 97:2 LXX;

(2) the description of God’s righteousness as the mercy he promised (“remembered”) for Israel

(Ps 97:3 LXX; Rom 3:21-26);

(3) the cosmic scope of his righteousness (Ps 97:4–8); and

(4) the forensic nature of God’s righteousness (Ps 97:9 LXX).

The psalm, then, not only provides Paul with righteousness language but a conceptual outline for how he explains the nature and scope of the revelation of God’s righteousness in the gospel.

-

Paul’s Quotation of Habakkuk 2:4 in Romans 1:17

The most important intertextual feature of Rom 1:16–17 is of course his citation of Habakkuk 2:4. Paul likely adjusts the citation by removing any trace of a possessive pronoun (“his faith/faithfulness”) which is reflected in Hebrew and Greek versions of the verse. In this way, he underscores the importance of the righteous figure’s faith in the prior promise of the gospel.

Moreover, what interpreters of Rom 1:17 often neglect is the function of Hab 2:4 in its original and wider prophetic context. It is, after all, the summative divine response to Habakkuk’s opening laments (Hab 1:1–4, 12–17). Habakkuk’s cries stem from two afflictions:

(1) the righteous have to live among the ungodly (Hab 1:1–4); and

(2) the righteous will have to live in the face of God’s impending wrath.

God ultimately responds to the prophet by stressing that the righteous will live in the midst of ungodliness, judgment of the ungodly, and beyond judgment through faith in the prior promise of deliverance which is provided in the vision of a divine warrior in Habakkuk 3.

Paul takes up this wider prophetic framework for his letter to the Romans. Those who are righteous by faith in Christ must also live in a world of ungodliness which is under divine wrath (Rom 1:18–3:20). Their hope in and beyond that judgment is faith in the revelation of God’s righteousness in the gospel (Rom 3:21–8:39). The affliction that the Romans now experience does not stem from God’s wrath against them, even if it appears as such (Rom 8:31–35). Even Israel’s unbelief (Rom 9–11) fits with the scripturally informed revelation of God’s righteousness.

Just as God answered Habakkuk’s cry with what he said in Hab 2:4, God answers the cries of Paul and the Romans in the same way, “The righteous will live by faith.”

-

Paul Use of Isaiah in Romans 1:16–17

A final intertextual layer in Rom 1:16–17 involves Paul’s use of Isaianic language as Robert Olson has recently noted. Paul specifically draws from Isa 28:16, 52:7, 10, 15, and 53:1. Faith in the Isaianic stone/suffering servant will not lead to eschatological disappointment/shame.

In tying these intertextual pieces together, as I write in the summary of Rom 1:16–17 in the commentary:

“Paul’s shorthand expression for the divine and effective work experienced in the gift of the gospel is δικαιοσύνη θεοῦ (God’s righteousness). In short, God saves the believing Jew and Gentile by judging them and their enemies in the crucified Christ. He also vindicates them by raising Christ from the dead. Paul and the Romans, as those justified by faith in the gospel, must live by faith in what God has done and will do in Christ. Although psalmist-like disappointment in the powerful promise of God is a real threat, Habakkuk provides Paul with the framework, or paradigm, for how the Romans should live and experience God’s saving work in Christ as they suffer from a variety of afflictions and concerns” (An Intertextual Commentary on Romans, 1:128).

B. J. Oropeza

I particularly like point #4 that you make regarding Paul’s use of Isaiah in 1:16–17. On the “not ashamed” allusion, I believe that such texts as Isaiah 28:16, 45:24, 50:7 have influenced it. The first of these Isaianic verses is cited in Rom 9:33 and 10:11, and the context of 45:24 is cited in Rom 14:11. Also, I strongly suspect that an oral tradition of Jesus, finally frozen in Mark 8:38 (cf. Matthew 10:33; Luke 12:9), influenced this reading (see my Jews, Gentiles, and the Opponents of God, 147–48).

Again, I see the influence of Isaiah in δικαιοσύνη θεοῦ (“God’s righteousness”). I have argued this in my article, “Paul’s Use of Deutero-Isaiah in Rom 2:24 and in the Gospel of Romans,” in Scripture, Texts, and Tracings in Romans (Fortress Academic), 31–49 (esp. 39–41, 46–47). In particular, Isaiah 51:5–8 uses the phrase δικαιοσύνη μου (“my righteousness” i.e., God’s righteousness) repeatedly in relation to salvation.

Thank you, Channing, for a stimulating discussion! I look forward to our second interview, which will focus on Romans 5:1–8:39.