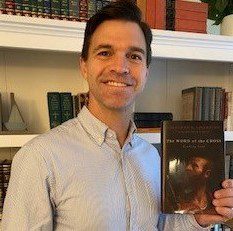

Jonathan Linebaugh’s recent book, The Word of the Cross: Reading Paul (Eerdmans) is the subject of this interview. Dr. Linebaugh is the Anglican Chair of Divinity and professor of New Testament at the Beeson Divinity School of Samford University. He was also an associate professor of New Testament theology at the University of Cambridge.

He has authored works such as God, Grace, and Righteousness in Wisdom of Solomon and Paul’s Letter to the Romans (Brill), God’s Two Words: Law and Gospel in the Lutheran and Reformed Traditions (Eerdmans), and coedited with Michael Allen, Reformation Readings of Paul: Explorations in History and Exegesis (IVP Academic).

It is my pleasure to interview him on his recent work.

The Interview with Jonathan Linebaugh

Oropeza: Congratulations, Jonathan, on another deep probing into Paul’s Letters! My first question is this: Who are the intended readers and what is your primary aim that you are attempting to get across to your readers in this book?

Linebaugh: Most of the chapters started their life as journal articles and seminar papers. That means the first audience was and still is students of the New Testament and scholars. I wrote in conversation with and hoped the book would lead to continued conversation with others engaged in the academic study of Paul’s letters.

I’ve been encouraged, however, to learn that Christian theologians, seminarians, and ministers have been engaging and benefiting from the book. I’ve heard various reasons for reading, all of which resonate with my reasons for writing—an interest in reception history, contextual and comparative interpretation, and theological exegesis.

But there also is a sense that Paul has something to say about the depth of human need and the wonder and hope of God’s mercy. If those kinds of threads can be tied together, the final hope for the book is to listen to Paul’s letters so we might hear the gospel Paul proclaimed—that merciful surprise he called “the word of the cross.”

The Word of the Cross

Oropeza: How does the title of the book, The Word of the Cross: Reading Paul, reflect thematically the content of the chapters?

Linebaugh: In 1 Corinthians 1, the phrase “the word of the cross” is both a summary and a surprise. Paul identifies “what we preach” as “the word of the cross,” and that announcement is a shock. It is “foolishness” and a “stumbling block.” The cross is the site of weakness and shame, of degradation and death.

According to “the word of the cross,” however, God acts in and through “Christ crucified” to overcome the conditions of the possible: “the cross is folly…but it is the power of God” and also “the wisdom of God” (1 Corinthians 1:18, 23-24). Not many among the Corinthians were “wise” or “powerful” or “of noble birth, but God chose what is foolish and weak in the world to shame the wise and the strong. God chose what is insignificant and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are” (1 Cor 1:26-28).

For Paul, this pattern is a promise, a proclamation of the gospel as a merciful surprise—at the place of foolishness, sin, bondage, and death God, “in Christ Jesus,” creates “wisdom” and “righteousness,” “liberation” and “life” (1 Cor 1:30).

That theme unites the book. Each chapter is an instance of “Reading Paul,” but only the first part does so without reference to other texts or traditions. The second section reads Paul in conversation with early Jewish literature, and the third reads Paul with later readers of Paul. What varies is the method. What emerges as consistent is the motif—the Pauline gospel is a merciful surprise.

Oropeza: Yes, I noticed that your book is divided into three sections:

In Part I, you address such topics as righteousness, grace, hope, and death and life in Christ from Romans 3, 4, 9–11, and Galatians 2. Part II is where you cover comparative readings of Paul with ancient Jewish texts such as 1 Enoch and the Wisdom of Solomon in relation to passages such as Romans 1:18–2:11 and 3:21–24. In the final section, Part III, you cover Paul in light of reception historical interpretations, engaging with how Thomas Cranmer and Martin Luther read Paul.

Linebaugh: Some lines from W.H. Auden capture the theme: “Nothing can save us that is possible/We who must die demand a miracle.” Paul’s diagnosis runs this deep: without ever ignoring or erasing particularity and difference, he announces a “we” beyond and beneath every “us” and “them” (see chapter 6), a fundamental bondage and need that “demands a miracle” of redemption and resurrection out of captivity and death (see chapter 4).

In Christ, and then in Israel’s canonical history (see chapter 3), Paul encounters the creator who promises beyond the possible—the God who, “according to grace” (Romans 4:4, 16), “justifies the ungodly” and also “gives life to the dead and calls into being that which is not” (Rom 4:5, 17; see chapter 2). For Paul, the gospel is Good Friday: it is Christ going into and given for those in the grave. But the word of the cross is also an Easter sermon that rolls away the stone. This, according to Paul, is the grammar of the gospel—not the old or the possible, but only the “grace of God” that is “the son of God who loved me and gave himself for me” (Galatians 2:20-21).

This pattern emerges in a particular way through both comparative readings of Paul and reception historical interpretations.

Oropeza: I see. Please tell us more about reading Paul in light of comparative conversations and reception history.

Linebaugh: Read in conversation with other early Jewish texts, Paul both shares a tradition and stands out within it—he reads the same scriptures, but interprets them differently (see chapters 2, 3, 5, and 8). He considers the relationship between Israel and the nations, but announces a fundamental solidarity “under sin” and “in Christ” (“there is no distinction,” Romans 3:23 and 10:12-13; see chapters 6 and 7). He speaks the language of righteousness and grace, but this inherited and canonical vocabulary is defined by the particular gift of Christ that reveals God’s righteousness as it is given to sinners and recreates them as righteous (see chapters 1, 7 and 8).

The reception historical studies consider readers of Paul—Martin Luther and Thomas Cranmer—who sensed and tried to find new ways to speak the merciful surprise. For Cranmer, this meant saying, “hear what comfortable words…St. Paul saith.” Luther emphasizes the surprise and the mercy, calling the gospel “strange and unheard of” while also insisting that it gives “rest to your bones and mine.”

For both Cranmer and Luther, this rest and this comfort is anchored in the incongruity of grace: “Christ Jesus came to save sinners,” quotes Cranmer; and as Luther writes, “God accepts no one except the abandoned, makes no one healthy except the sick, gives no one sight except the blind, brings no one to life except the dead,” and “makes no one holy except sinners.”

These Reformation interpretations sometimes entail translating Paul into new contexts and idioms, but the deep exegetical question is not so much whether later interpreters used the same words as Paul. The question is whether they proclaim the same word as Paul—the word of the cross.

The Pauline gospel does not promise the possible: “we…demand a miracle.” But as Ernst Käsemann put it, the “impossible is not the boundary of hope,” because “hope” is born “where graves cannot hold the dead.” That is the merciful surprise: God gives Christ, incongruously, to the bound, sinful, and dead; and Christ, impossibly, creates freedom, righteousness, and life.

The Righteousness of God Revealed

Oropeza: In Part I, in the chapter entitled, “Righteousness Revealed: The Death of Christ as the Definition of the Righteousness of God in Romans 3:21–26,” I like your Christological-gospel emphasis for the term, “The Righteousness of God.” If I’m reading you correctly, you say that Christ’s death on the cross is “the eschatological enactment of the final judgement” (p. 12). And different than N. T. Wright—who teaches that present justification anticipates the future verdict of God (God’s acquittal or “not guilty” declaration at final judgment)—you hold that “the future word of justification is an echo and effect of the justifying judgment enacted in the cross” (p. 13 n. 32).

Could you elaborate more on this? If this word of justification is in the future, what does our present justification/righteousness look like? Does it include God’s forgiveness of our sins and union/participation in Christ through the Spirit?

Linebaugh: There’s a poem by George Herbert, Justice II, that opens in a mood of fear because “sin and error…show and shape” the perception of God’s righteousness. At the midpoint, however, Herbert echoes Paul in Romans 3:21: “But now that Christ’s pure veil presents thy sight/I see no fears…” Because what finally “shows and shapes” the righteousness of God is not “sin and error” but “Christ.” The poet hears God’s judgment already pronounced: “God’s promises have made thee mine;/Why should I justice now decline?/Against me there is none, but for me much.”

According to Paul, the righteousness of God is witnessed to by the law (Rom 3:21) and is revealed “in it,” that is, in the gospel (Rom 1:16-17). And that gospel, which is “the power of God for salvation” (Rom 1:16), is “the gospel…about God’s son” (Rom 1:1-4). This comes together in Romans 3:21-26: God’s righteousness revealed in the preaching of the gospel about God’s son was made visible and enacted in what Paul calls “the redemption that is in Christ Jesus.”

In Romans 2, God’s patience precedes the future righteous judgment of God (Rom 2:4-10). In Romans 3, that patience becomes past and that promised act of righteousness becomes present: “God put Christ forward as a sacrifice of atonement… God did this to demonstrate his righteousness, because in his patience he had left the sins committed beforehand unpunished—he did it to demonstrate his righteousness at the present time” (Rom 3:25-26). Paul calls this gift and grace (3:24), and it creates what appeared to be impossible.

As a future judgment was imagined in Romans 3:20, the conclusion is condemnation: “all flesh will not be justified.” But when that future judgment breaks into the present in the gift of Christ, the surprising new reality is that the “all sinned” of Romans 3:23 become the “are justified” of Romans 3:24.

It is not so much that justification is in the future. It is that the future is in the present: God’s final judgment has been enacted and spoken in Christ. What God says “in the present time” does not only anticipate but actually is the final announcement, the word that God will say again—and say on the same Christological basis—at the future judgment: in Christ, by grace, you are righteous. This judgment does not locate and confirm an already existing reality; this judgment, in Christ, comes into the conditions of bondage, sin, and death and creates the new reality of freedom, righteousness, and life.

Oropeza: In your next chapter, “Promises Beyond the Possible,” I notice that you connect this idea from Romans 3 to Romans 4.

Linebaugh: In Romans 4, Paul sees that this pattern of God promising beyond the possible and creating out of the opposite has shaped the history of Israel from the beginning. Isaac is born out of the deadness of Abraham’s age and Sarah’s bareness, in Abraham we see that God “justifies the ungodly,” and all this—this action of the God “who gives life to the dead and calls into being that which is not” (Rom 4:17)—is the pattern of mercy we meet in the God “who raised our Lord Jesus Christ from the dead” (4:24).

For Paul, the site of God’s enactment of righteousness and the ground and location of God’s creative pronouncement of righteousness is Jesus Christ. God’s righteousness is revealed in the gospel about God’s son; God’s righteousness is carried out in the redemption that is in Christ Jesus. And it is in “in him”—that is, “in Christ”—that “we become the righteousness of God” (2 Cor 5:21); it is “Christ” who is “our righteousness” (1 Cor 1:30).

This raises a web of questions about how Christ (him, then, there) is related to those whom he loved and gave himself for (us, now, here). Chapter 12 engages this question directly, exploring the relation of promise and faith and attending to the activity of the Spirit as the one who gives the Son who gave himself, joining us, by grace, to the one who still and always loves us and gives himself to us.

Faith in Christ/Faithfulness of Christ as Christological

Oropeza: In ch.11 of your book, I see that you cover the subject of “faith in Christ”/ “faithfulness of Christ” (πίστις Χριστοῦ/pistis Christou) in Galatians 2:16 when engaging with Martin Luther’s view. Could you elaborate on your viewpoint and insights gleaned from Luther?

Linebaugh: Chapter 11 isn’t an attempt to settle the pistis Christou debate or even to offer a full argument for one reading or another. The thesis is more focused: “faith in Christ,” for Martin Luther (and for many others), is Christological.

Oropeza: In recent decades, those who support the “faithfulness of Christ” interpretation are the ones who often claim that their view is Christocentric. The way you are reading Luther, however, is quite different than this.

Linebaugh: The exegetical debate is regularly cast in terms of an anthropological or anthropocentric interpretation (i.e., faith in Jesus Christ) over against a Christological or Christocentric interpretation (i.e., the faithfulness of Jesus Christ). The problem with this rhetorical contrast is that the equation “faith in Christ equals anthropocentric” doesn’t describe how Luther reads Paul.

Because Paul defines faith antithetically (“not works of the law, but…”) and also in relation to Christ (“faith in Jesus Christ”), there is, for Luther, a double “alone”: sola fide (“faith alone”) excludes the anthropological as it receives and confesses solus Christus (“Christ alone”). Karl Barth captured this with a question: “What is the sola fide other than a faint echo of the solus Christus?”

For Luther, sola fide is an interpretation of Paul’s antithesis—“not by works of the law, but through faith in Jesus Christ.” The result, rather than an anthropological reading of Paul, is an anthropological “no” and a Christological “yes”: it negates the human as the subject of salvation and confesses Christ, who is present in faith, as the one by, in, and on the basis of whom God justifies the ungodly. In Luther’s own words, “faith takes hold of and possesses this treasure, the present Christ,” and therefore “the true Christian righteousness” is “the Christ who is grasped by faith…and on account of whom God counts us righteous.”

It is because the Pauline pattern, as Luther understood it, is “not I, but Christ” that he could say “our theology is sure.” Rather than focusing on faith, justification through faith in Jesus Christ “snatches us away from ourselves and places us outside ourselves, so that we do not depend on our own strength, conscience, experience, person, or works but depend on that which is outside ourselves, that is, on the promise and truth of God.”

Union with Christ

Oropeza: Galatians 2:20 is one of the primary passages on union with Christ. Paul speaks of being crucified with Christ, and it is no longer he that lives bur Christ who lives in him. How do you engage with and interpret this verse in ch. 4 of your book?

Linebaugh: That chapter opens with lines from Augustine that capture the strangeness of Paul’s confession about having been crucified with Christ. Augustine notices that Paul’s way of talking is a genre for those already in (and now out of) the grave: it is, he says, “the speech of the dead.” “I no longer live,” says Paul, who then adds, “the life I now live…”

As Augustine tries to speak through this Pauline idiom, he says surprising things: “I am not I, I am,” or again, “they who are already dead [are] living.” Other readers have recorded surprise and confusion: “strange and unheard of” (Luther), “inconceivable” (Schweitzer), “we seem to lack a category of reality [for] real participation in Christ” (E.P. Sanders). Chapter 4 lives with and leans into this strangeness by asking one question: Is (or are) the “I” that no longer lives and the “I” that now lives the same someone?

Paul’s confession both suggests an unexpected order—death then life—and invites a redefinition of death and life in relation to “the son of God who loved me and gave himself for me.” Death is “I have been crucified with Christ” and life is “Christ lives in me.” This indicates a rupture: “I died to the law,” “I have been crucified with Christ,” “I no longer live.” And then: “I live to God,” “the life I now live.” But this “life I now live” isn’t life before death; it is life after and out of death with Christ. The history of each “I,” you might say, is marked by two days: Good Friday— “I have been crucified with Christ”; and Easter—“Christ lives in me.”

In one sense, then, “no” is the Pauline answer to the question, “Is the no longer ‘I’ and now living ‘I’ the same someone?” Death and life divide the no longer and now living I, and the life of the latter is gifted and located outside of the person and in Christ.

But the answer is also “yes.” For Paul, the cross is at once a death that breaks the story of the self into two even as it is a gift and love that holds it together. As Paul’s confession concludes, “the son of God loved me and gave himself for me.” It seems, before and beyond the “I no longer live,” there is a “me” that Christ loved and gave himself for (see also Gal 1:4; Rom 5:6-8).

The persistence of the person is not grounded in the person: I am “not I, but…” by grace and in Christ. It is exactly this grace and this Christ, however—the one who loved me and gave himself for me—that establishes a kind of continuity. The “I” may no longer live, but the “me” was and is loved.

To speak “the speech of the dead” is thus to talk twice: death and life separate the self. And yet, in and across the passages of creation, sin, grace, and glory there is a “me” for whom Christ died, a “me” whom Christ ever has and ever will love.

Oropeza: We will end on that note. If the readers want more, they should buy the book. Thank you, Jonathan!