Did Paul forbid women from speaking at the Corinthian church? With 1 Corinthians 14:34–35 as our model, yes, they were to keep quiet, but what does this mean? A number of biblical interpreters point out that Paul permits women to prophesy at church in 1 Cor 11:5. Hence, unless our apostle is contradicting himself, 1 Cor 14:34–35 cannot mean an absolute ban on women speaking. It also follows that if they were allowed to prophesy, Paul would hardly prevent them from using other speaking gifts such as teaching.

Paul’s rhetorical wish that “all” would speak in tongues and prophesy becomes rather empty if he is precluding all the women from doing so (1 Cor 14:5). Moreover, “each” person in the congregation would seem to include women who can speak in tongues, interpret, give a revelation, teach, sing, or use another speaking gift (1 Cor 14:26). Such inspired speaking involves spiritual gifts that the Spirit distributes to each believer (12:7–11), and nothing suggests that these gifts are given only to men.

If Paul agreed with the early Christians who associate the Spirit’s outpouring with Joel 2:28–32 (cf. 1 Cor 1:2; Acts 2:1–22), this would seem to confirm that prophetic and spiritual speaking are not just given to “sons” but also “daughters.” The gifts of the Spirit do not discriminate according to gender.

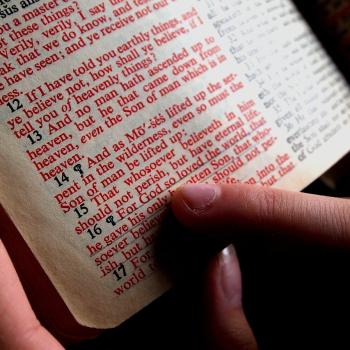

What, then, does Paul mean when he says in 1 Cor 14:34, “Let the wives in your assemblies be silent, for they are not permitted to be talking but to be in submission, just as the law says also”? (my translation from B. J. Oropeza, 1 Corinthians).

Are the Women Speaking or Chatting?

I understand women in 1 Cor 14:34 to be mean “wives” (gynaikes/ γυναῖκες). The context clarifies this nuance when Paul affirms that these women have husbands (see 1 Cor 14:35).

When Paul writes that these wives are not permitted to speak, the Greek verb is laleô (λαλέω). It is better understood here as “talking” or even “chatting” instead of “speaking” (compare Eph 4:25; 2 John 12; and further examples in Oropeza, 1 Corinthians, 188). Again, context is determinative. We read in 14:35a that if the wives “wish to learn anything, let them ask their own husbands at home.” This implies that these women were asking questions at church, apparently disrupting the inspired speaker’s message with inquiries.

Sifting the Prophetic Speaker?

Certain scholars suggest this activity involved “sifting” the prophet’s words and cross-examining them with questions regarding their lifestyle or beliefs in public. This would be especially controversial if the wives were probing the prophesies of their own husbands this way.

But there are some problems with this viewpoint:

First, at least some questioning about the prophecies would doubtless include the gift of discernment (1 Cor 14:29; cf. 12:10). If so, then we are hard pressed to affirm either that only men could use this gift or that a wife’s evaluation could never pass for such discernment.

Second, another problem is that Paul’s recommendation for wives to learn from their husbands privately seems to have little to do with their evaluating and challenging the speaker.

Uninspired Questioning

A better explanation is that the wives’ questions must have been understood as uninspired. Perhaps some of them interrupted the speaker, not to challenge him or her but to ask for clarification of what was being uttered.

Moreover, these women may have been asking questions to their husbands about what another speaker was presently saying. They may have been asking husbands or other wives nearby such things as, “What do you think he means?” “Could he be saying that . . . ” “Is she referring specifically to me? What she’s saying actually happened to me this week when I . . . ” Such questions presumably sparked chatting in congregation instead of keeping quiet as the speaker or prophet spoke.

The confusion perhaps originated because many gatherings met in homes. The problem was taking place in the “assemblies” (ekklesiai). This does not refer to “churches” in the modern sense of the word, let alone the church worldwide. Rather the word refers to the various houses and facilities where Corinthian believers gathered for worship. At this time, there was no centralized “church” building; believers met in homes, tenements, workshops, and other places to worship together and hear the word of God.

Whereas chatting and asking questions might be acceptable in the privacy of one’s own home, it was not to be done in homes and other facilities used for sacred gathering open to the public. Bottom line: Paul is forbidding wives from uninspired talking when others are inspired to speak at the house gatherings. Their talking in this context has to do with questioning rather than teaching, proclaiming, and praying.

Kenneth Bailey on Women Chatting

Kenneth Bailey, who has extensive experience working with women in Mediterranean villages, says that chatting is still a problem in these church gatherings. He attributes this to factors such as lack of education and social contacts, along with short attention spans that such things might induce.

The problem in 1 Cor 14:34–35 may involve similar factors in which chatting becomes a way of learning. Hence, the chatting of these women, along with both genders inappropriately using tongues and prophecy, hinder orderly worship. Paul requests the culprits of all three to be silent in church (1 Cor 14:28, 30, 34). For the latter he essentially says, “Women, please stop chatting so you can listen to the women (and men) who are trying to bring you a prophetic word but cannot do so when no one can hear them.” (Paul through Mediterranean Eyes, 416; cf. 412–17).

Women are to be Silent and Submit according to the Law?

Paul writes that the wives must therefore be “silent” and “submit” themselves to the speaker under divine guidance in reverence to God, whoever he or she might be. This silence and submission is in accordance with the “Law,” that is, biblical Scripture (1 Cor 14:34; cf. 14:21).

What verse in the Law speaks about silence and submission? Some suggest this refers to the curse of Eve in Genesis 3:16. But this verse does not appear to be what is referenced since silence and submission are foremost to be given to the speaker rather than a woman’s husband. In any case, nothing is said about silence, whether in Gen 3:16 or in the context of the creation discourse in Gen 1–3.

Rather, in the Law, Aaron and Miriam’s rebuke related to questioning Moses’s prophetic authority comes closer to what Paul means (Numbers 12:1–15). Paul alluded to this story earlier (see 1 Cor 13:12), and if it is echoed here, then reverence to the prophet seems required of both genders.

Quiet Reverence for the Inspired Word

Silence and reverence are to be given to God and the prophetic word (Habakkuk 2:20; Zephaniah 1:7; Zechariah 2:13). Commenting on worship in Habakkuk’s context, O. P. Robertson writes, “One should wait upon him [God] in the awed silence that is often the most appropriate expression of true worship” (The Books of Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, NICOT: 212). Marvin Sweeney affirms that Zeph 1:7 “constitutes the prophet’s exclamatory demand for silence at the beginning of the presentation of YHWH’s oracular statements that announce the coming Day of YHWH” (Zephaniah, Hermenia: 78).

It seems to be standard protocol, then, that in the Scriptures which inform Paul, silence is required whenever a prophet speaks divine words. This idea is what Paul probably means by referring to the Law (= Scripture: notice that “the Law” refers even to prophetic discourse in 1 Cor 14:21).

Elsewhere in Scripture the notion of silence is encouraged when hearing wise counsel (Job 29:21), and is also to be given in respect for those in authority (Judges 3:19).

In Acts, Peter and Paul’s motioning of the hand to silence their audiences assumes both unruly commotion among their auditors and the necessity for them to be quiet as the apostles speak (Acts 12:17; 21:40). Likewise in the Qumran Community who wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls, talking during the discourse was forbidden (Community Rule, 1QS 6.10–13).

Such texts evince that ancient audiences could be quite noisy. Men as well as women might be guilty of disrupting the speaker, and so we surmise that the only reason Paul does not silence men or husbands from chatting in the Corinthian setting is because they were not the problem.

On Speakers, Silence, and Shame

The additional phrase in 14:35b, “for it is shameful for a wife to talk in an assembly” equates this activity with what is unacceptable and dishonoring. It would surely be shameful according to cultural norms of the time for a wife to talk in a way that embarrassed her husband publicly. Again, this was happening not necessarily because wives challenged their husbands as speakers, but because they were asking questions to their husbands about other speakers and interrupting or distracting those speakers and the ones who heard them.

The Greco-Roman world of that time would agree. The philosopher Plutarch considers it rude and disrespectful when audiences interrupt the lecturer or ask uneducated or irrelevant questions (Moralia 39C; 42F–43C; 48A–B). Anaximenes’s rhetorical handbook recognizes interruptions as a peril orators face. Among his solutions is that orators are to meet interruptions by showing them as contrary to justice, law, and what is honorable and publicly advantageous (Rhetorica ad Alexandrium 1433a.25–29; cf. 14–18).

Paul would seem to agree that in worship assemblies distractive talking is shameful and runs counter to Scripture. As such, the Corinthian wives were disrespecting the speakers and the Spirit who inspired them.

The inspired speakers, I should add, could be either men or women. Paul did not prevent inspired women from speaking in the Corinthian churches; he only prevented uninspired chatterers from speaking.

* * *

Next up: 1 Timothy 2:9–15…