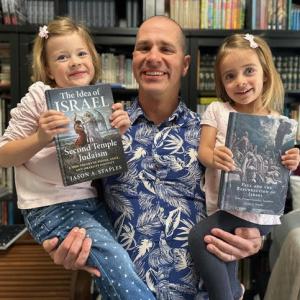

We are back for a third and final round with some more questions for Jason A. Staples, based on his recent book, Paul and the Resurrection of Israel: Jews, Former Gentiles, Israelites (Cambridge University Press, 2024). He teaches as a professor in the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at North Carolina State University.

Our previous episodes covered Israel’s restoration (Pt. 1) related to the end times, and Pt. 2: Jewish identity, living by the Law (Torah), and Christ as the “end” of the Law. For the conclusion we will address Dr. Staples’s view of the new covenant, fullness of the gentiles in Romans 11:25-26, and use of the term, pneuma (spirit).

The Interview: Part 3

Oropeza

In your book, I like your emphasis on the new covenant in Jeremiah 31:31–34 (Hebrew text/ Jer 38:31-34: Greek Text, LXX). This passage is echoed in the texts of the Lord’s Supper, both in the Gospels and Paul (1 Corinthians 11:23-26), again in 2 Corinthians 3:3–18, and yet again in Hebrews.

I’m curious, how do you think Paul read Jeremiah 31:32? It says that this new covenant God will be establishing is not according to the covenant God established with their fathers when taking them out of Egypt. In other words, the text appears to be saying that the new covenant would not be the same as the Mosaic covenant.

Staples

I think Paul understands the difference as spiritual (pneumatic) versus fleshly. The problem with the previous covenant was the incapacity of the fleshly people to keep it. Thus “the Torah was powerless because it was weak through the flesh” (Romans 8:3).

Here I think Paul is very much in agreement with Hebrews 8:8, which says that the problem with the “first covenant” was the people. The solution is therefore the transformation of the people, thus addressing the fault of the first covenant.

As Paul understands it, the difference is that rather than being inscribed on tablets of stone, the new covenant is inscribed on the heart. And rather than requiring a fleshly people to keep a spiritual Torah, the new covenant makes the people spiritual (pneumatic).

Oropeza

One of the unique interpretations in your book is that you argue for a connection between the fullness of the nations/gentiles in Romans 11:25–26 and a parallel in Genesis 48. Could you elaborate on this?

Staples

In Romans 11:25–26, Paul tells the gentiles in the church, “a partial insensibility has come upon Israel until the fullness of the nations has entered, and thus all Israel will be saved.”

This phrase, “the fullness of the nations” appears only one other time in early Jewish literature. That other instance is in Genesis 48:19, where the patriarch Jacob/Israel crosses his hands when blessing the children of Joseph, explaining that whereas the firstborn Manasseh would become a great people, “his younger brother [Ephraim] will be greater than he, and his seed will become the fullness of the nations.”

This passage is highly significant in the narrative arc of Genesis. Previously, Abraham was promised that “by/in you all the families will be blessed” (Gen 12:3) and “in your seed all the nations of the land will be blessed” (Gen 22:18). That specific blessing is then passed to Isaac (Gen 26:4), who then passes it to Jacob/Israel (Gen 27:29). Then, at the end of Genesis, Ephraim is chosen as the heir of this blessing, with the twist that “his seed will become the fullness of the nations.”

I don’t think it’s accidental that Paul employs such an unusual phrase from such a climactic passage at the climax of his own argument, right at the moment he explains how “all Israel“—not only Jews but the non-Jewish portion of Israel—will be saved.

Oropeza

I recall reading that you connect Hosea also to this argument?

Staples

Paul has already cited Hosea’s promise to northern Israel, whom God had divorced with the words “you are not my people and I am not your God” (Hosea 1:9). He states that God would one day restore them: “I will call those who were ‘not my people’ ‘my people’” (Romans 9:25; Hosea 1:10/2:1).

But Paul interprets that promise of northern Israel’s restoration as though it referred to the nations (Romans 9:24). On the one hand this is a surprising move, but on the other this is perfectly sensible. After all, what would “not my people” mean if not “gentiles”?

Here Paul seems to understand Israel’s divorce (cf. Jeremiah 3:8) as resulting in Israel’s “gentilization”—having wanted to be like the nations, they assimilated among the nations, their children becoming no less gentiles than the nations in which they were scattered. Or, as 2 Kings 17:15 says, “They went after the nothing and became nothing/empty” (cf. Romans 1:21).

I should add here that these passages are not about Jews, of whom it was never said, “you are not my people.” Nor would any Jewish interpreter read, “you are not my people” as referring to Jews. Instead, this specifically refers to Israel. But the Prophets continue to promise Israel’s restoration and reunion with Judah—all Israel will be saved, not just Judah.

The question is how such a thing could happen if Israel had de facto gentilized. Thus, Paul argues that the gentiles receiving the spirit are being both ethically and ethnically transformed in a divine action that amounts to life from the dead (Romans 11:15), Israel’s promised resurrection from dry bones (Ezekiel 37).

Thus, when Paul quotes Genesis 48:19 at the climax of his argument, he is explaining how God is restoring all Israel, even including the portion that had long since ceased to be Israel by incorporating gentiles within the people of God through the transformation by the spirit granted by Israel’s messiah.

Oropeza

I notice that you use the lower case “spirit” when addressing texts that are normally attributed to the Holy Spirit by other interpreters. Why is this?

Staples

Part of it is just convention; the default these days is to default to lowercase. I don’t capitalize pronouns referring to deity, for instance.

Another part is that I’m trying to be faithful to the Greek texts as I understand them. I’m a firm believer in the principle that if the source passage is ambiguous, a translation should strive to be equally ambiguous if at all possible.

As you know, the ancient manuscripts themselves don’t distinguish “spirit” from “Spirit,” and it’s not always clear where (or if) Paul is thinking along the lines of “the Holy Spirit” in trinitarian terms.

Take Romans 1:4 for example, where Paul says Jesus was “determined the son of God in power through a spirit of holiness.” Is Paul here referring to “the Holy Spirit” in a personal third-member-of-the-Trinity fashion? If so, why the strange way of saying it?

One can certainly read such passages (and other passages in which Paul refers to “spirit” or “the spirit” without the “holy/sacred” adjective) in a trinitarian fashion. But as a historian, I didn’t want to predetermine that interpretation for my readers in my translations and discussions.

Oropeza

Neither would I. I would not want to add “Holy” to “S/spirit” unless the Greek actually stated this, nor would I assume already that any instance of πνεῦμα (pneuma) in Paul must refer to God’s Spirit.

Staples

By keeping “spirit” in lowercase throughout, I tried to maintain the same level of ambiguity that’s present in the texts themselves, allowing my readers to draw their own conclusions rather than deciding for them.

Oropeza

It’s been a pleasure, Jason, conversing with you. I hope your book gets the attention it deserves. Thank you for taking the time to do this interview!