Similar to the early Jesus believers, Philo of Alexandria valued the concept of faith in his writings (in Greek: πίστις/ pistis). In relation to God, he seems to have understood this term generally as trust, as we shall see.

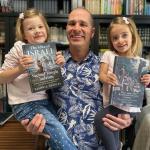

Philo was a Hellenistic Jew who lived during the time of Christ (c. 20–50 CE). Many of Philo’s writings survive including a number of treatises and commentaries related to Mosaic Law. He is also considered a Middle Platonist, a term used of philosophers influenced by Plato from roughly the first century BCE to about the middle of the third century CE. For more on Philo, see for example, Reading Philo, edited by Torrey Seland (Eerdmans).

Philo’s Use of Faith — Pistis

Philo uses what we often translate as “faith” (pistis) in different ways. For example, he frequently understands the term as “proof” or “evidence.” This proof for Philo as a Jew often relates to Jewish Scripture, the Old Testament.*

For Philo, pistis is also the “queen of virtues” (On Abraham [Abr.] 270; cp. On the Virtues [Virt.] 216).

In reference to God, Philo uses pistis to refer to divine promises, God’s own disclosure to God’s people, and trusting in God (e.g., Philo, On the Change of Names [Mut. Nom.] 182, 201). According to Teresa Morgan, “Philo treats pistis towards God as a key development in the relationship of a righteous person with God. It is within a relationship of trust in God that we learn what the truth is” (cf. Roman Faith, Christian Faith, 153; henceforth, RFCF).** A prime example of this is Philo’s interpretation of Abraham.

Abraham’s Faith as Trust

In Genesis 12:1–3, Abraham sets out from the land of Ur of the Chaldeans to the land that God promises to show him, and God will make him into a great nation. In Abraham “all the families of earth will be blessed.” Philo sees this move from Genesis in terms Abraham’s hope of what God promises to do; this prompts his pistis, or “trust” (Migration of Abraham [Migr.] 43–44).

In Genesis 15:6 the Scripture says that Abraham believed God regarding God’s promise that his future posterity would be like the stars in heaven in number. And his faith was reckoned to him as righteousness. Philo writes regarding this verse that Abraham put his trust in God. (Who is the Heir, [Her.] 90–94; cp. Abr. 270; Virt. 216).

Philo claims that this kind of trust (pistis) is difficult: “it is not easy to believe in God on account of that connection with mortality in which we are involved, which compels us to put some trust in money, and glory, and authority, and friends, and health, and vigour of body, and in numerous other things; but to wash off all these extraneous things, to disbelieve in creation, which is, in all respects, untrustworthy as far as regards itself, and to believe in the only true and faithful God” requires a great and celestial undertaking (Her. 92b–93a; Yonge tr.).

Righteousness attributed to such trust makes proper sense to Philo, “for nothing is so just or righteous as to put in God alone a trust which is pure and unalloyed” (Colson, Whitaker, Earp, tr.).

Assessing Philo on Abraham’s Pistis

Morgan affirms that such pistis arises partially from Philo’s Platonism and partially from Jewish Scripture, and that trust (pistis) assumes that God is both trustworthy and interested in humans.

Moreover, according to Philo, it is not human lack of knowledge that prevents them from trusting God; rather, their moral weakness prevents them. Such frailty leads to these humans unfortunately trusting instead in “untrustworthy human phenomena” (RFCF, 154).

For Philo, those who hope in God for the future (and present and past) are rewarded with “trust.” If this type of trusting carries with it some kind of element of risk, then “trust in an interested divine being is likely to be a risk worth taking” (RFCF, 154).

Take Homes on Philo’s Pistis

Generally speaking, Pistis, the word we read repeatedly as “faith” in our Bible, may be better understood as trust.

To be sure, Philo is just one of a number of voices that can be heard from first-century Hellenism. He nonetheless is an example of a larger amount of ancient evidence suggesting that the Greek word pistis, which is often translated as “faith” in the New Testament, seems to have been better understood as “trust.”*** Of course, this is not to say that trust is the only nuance of pistis—the word takes on various senses depending on its context, including loyalty, belief, proof, allegiance, persuasion, evidence, faithfulness, and so on.

To place one’s pistis in Christ would likely suggest for his first-century followers not merely that they believe in him for their initial assurance to “make it to heaven.” Nor does pistis seem to be foremost exemplified by reciting a creed about who Jesus is and what he did, important as that may be. Pistis involves their complete trust in Christ, for he himself is trustworthy. This reliance on him would involve selfish abandonment. It would seem to take on the form of continued commitment, renewed daily, in a trusting relationship with Christ that included living one’s life for his sake.

Notes

* Useful for identifying and discussing Philo’s sources on pistis is Teresa Morgan, Roman Faith, Christian Faith (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 151–56, whose study I heavily draw on here. References here include, On Flight and Finding [Fug.] 136; On Abraham [Abr.] 141; Life of Moses [Vit. Mos.] 1.247; On Dreams [Somn]. 2.220; Special Laws [Spec. Leg.] 2.143. Further on Philo and faith, see Benjamin Schliesser, “Faith in Early Christianity: An Encyclopedic and Bibliographical Outline,” in Glaube, ed. Jörg Frey, Benjamin Schliesser, Nadine Ueberschaer (Mohr-Siebeck, 2017) 4–50, esp. 9-10.

References to Philo’s works in English can be purchased in book form. Perhaps the most accessible is The Works of Philo, C. D. Yonge translation (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1995). A more authoritative set in both Greek and English is found in the Loeb Classical Library (Harvard University Press; tr. F. H. Colson, G. H. Whitaker, and J. W. Earp).

** Morgan references from Philo, e.g., On the Posterity of Cain [Post.]. 13; Confusion of Tongues [Conf.] 31; On Abraham 270, 273; On Dreams 2.68.

*** For example, Plutarch, a non-Jewish Middle Platonist born in the same century as Philo, similarly uses pistis in relation to the trustworthiness of the gods, among other things (Moralia 170e; 359f–60b).