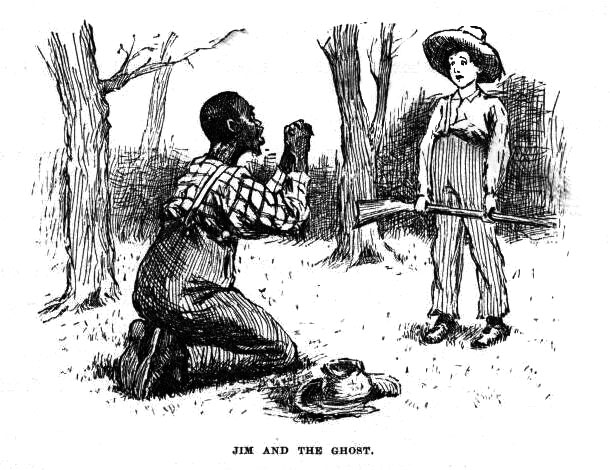

B.D. McClay continues the conversation about A.O. Scott’s essay on the death of adulthood. The accompanying illustration itself is worth a reading of the post. McClay aims to clarify further what is meant by the word “adult.” He spots a promising literary example in Huck Finn, and contemplates that the real test of adulthood is awareness and execution of moral agency:

Fiedler (and Scott) both focus on the great refusers of American literature, particularly Huck Finn, who decides to go to Hell rather than turn in his friend Jim, the escaped slave. But his refusal to hand Jim over isn’t a refusal to become an adult; it is a decision that shows he is one. He’s become a real moral actor. He doesn’t simply do what he is told, and he accepts the consequences of his choices.

Huck’s adulthood is made obvious when Tom Sawyer appears at the end of the novel. Tom sees only a potential adventure in Jim’s plight, and unnecessarily draws out Jim’s hopes of freedom—ultimately for no reason at all. Tom isn’t intentionally cruel, but he’s still a child and cannot understand the stakes. Huck may remain a vagrant, or at least an outsider, while Tom is likely to settle down, marry, and become a productive citizen. Yet Huck is, and will likely remain, the more adult of the two.

While I’m not quite sold on that last line, I think McClay has a solid illustration in Huck. I want to tilt the conversation a little bit away from the definition of “adult” for a minute though.

The “Alright, I’ll go to hell” passage is something I’ve seen appealed to quite a bit by those who argue that religious dogma and authority is naturally thrown aside by a mature moral consciousness. It’s at this moment that Huck realizes that the moral language that he’s been raised with–in this case, about Negroes–is untenable. Note that I didn’t say “false,” since the power of the narrative is not in Huck’s sudden moral knowledge but in his willingness to be accursed for the sake of his friend. Secular and religiously leftward commenters hold this moment up as an example of the liberating power of common morality over traditional dogma; thus, it is said, we need to be careful to orient ourselves like Huck, willing always to discard traditional or received notions the moment they conflict with our social and sexual experiences.

Huck is the modern heretic, the mind that is liberated from tradition by knowledge and experience. Joining back up with McClay, we see that Huck’s emergence into adulthood occurs simultaneously with his willingness to be damned. Put differently: Huck’s desire to be holy is replaced with a desire to be humane. And this, some say, is the quintessential American adulthood: The leaving behind of authority structures and journeying towards self-actualization.

Now McClay is referring merely to Huck’s moral agency. Without authority’s hovering him, Huck makes a decision and vows to live with the (potentially eternal) consequences. That, for McClay, is the essence of adulthood. And yet, McClay concludes with this paragraph, which suggests that the spiritual dimension is not entirely disconnected:

Being an adult in America, even aspirationally, has more to do with being a self-governing citizen than with leaving the family nest. Casting off childhood comes in recognizing oneself as a responsible moral actor. Maybe looking around and noticing that “no one is in charge” is not a sign that there are no adults—but, instead, a sign that you are one.

The phrase in quotation is taken from Scott’s essay, where he observes that contemporary cultural output is one that “imagines a world where no one is in charge.” From Huck’s perspective, deciding not to return Jim to a life of slavery might offend God, but if so, that’s OK. It might be a stretch to say that “no one is charge” in Huck’s new moral universe, but it’s probably safe to say the old guard has washed out.

Lest I be accused of over-reading McClay’s post, yes, I do know that McClay’s point is not that Huck’s adulthood is his heresy. But I do think the evaporation of authority, the flattening of information and the demise of experts all have something very important to do with Scott’s observations about adulthood. The example of Huck Finn is a doubly appropriate one, since not only does Huck transition into adulthood via moral acting, but said transition has a definite departing point, namely, trust in tradition and taught principles. It could be that our modern idea that adulthood entails a conscious tossing aside of received tradition and authority hasn’t actually created a more adult society. It could be that, even as (according to McClay) leaving the “nest” physically isn’t a reliable indicator of adulthood, neither is leaving it metaphorically. Perhaps “owning one’s beliefs” might be invested with more significance than it really deserves.

None of this, by the way, should be construed as saying that Huck’s decision was wrong. The illusion of the non-humanity of slaves was burst violently by Huck’s friendship (it is also obliterated by Christian Scripture). The point is that the ritual of casting off what one has been taught is probably not the pivot into adulthood that we might, even subconsciously, believe. Receiving and following and treasuring tradition might carry the risk of perpetuating injustice, true. That is why moral codes that transcend mere custom are necessary in the first place. But when faced with a culture that lacks real sense of growing up, we should ask whether aspiring to be a heretic alongside Huck is the right decision. Perhaps in taking so much pleasure in remaking ourselves every generation, we have simply created an endless childhood.