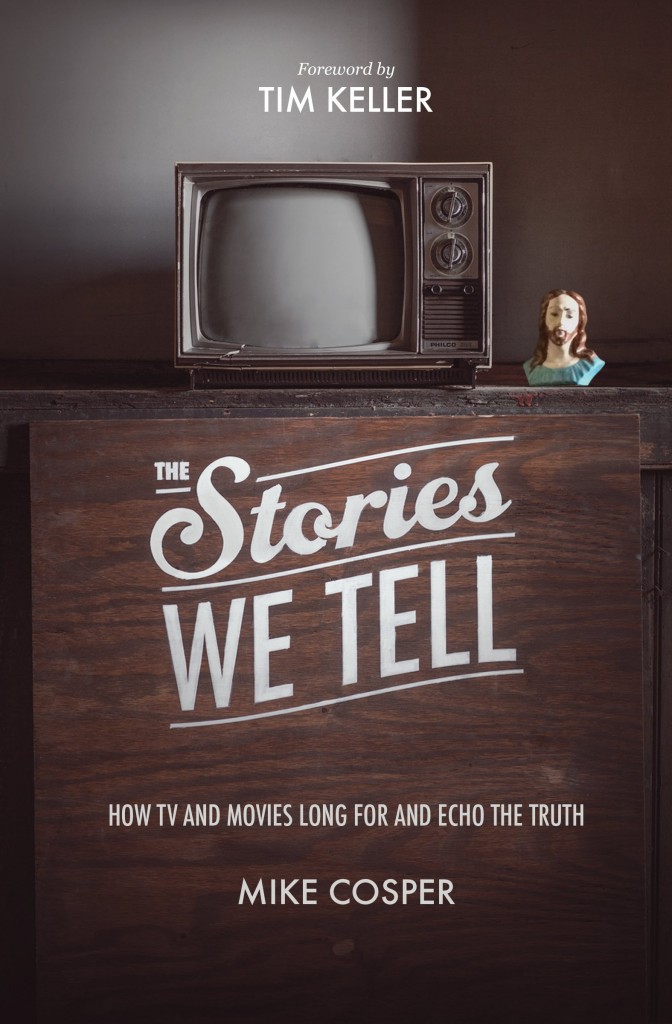

Last week I wrote a review for The Gospel Coalition of a helpful new book called The Stories We Tell: How TV and Movies Long For and Echo the Truth. Author Mike Cosper is a pastor here in Louisville, but he writes more like your smartest moviegoing friend who also happens to have a degree in theology. I think the more Christians–especially evangelicals–who read this book, the better and more fully Christian our conversations about pop culture (which is much, much more important than you think) will be.

Here’s a portion of my review:

You don’t need a philosophy degree or a robust knowledge of sociology to understand the power of stories, however. The Bible itself is one Story, a true tall tale with the triune God for its Author. The story of redemption is not just a story, but the story, as Cosper makes clear:

At the heart of our faith is the bold claim that in a world full of stories, with a world’s worth of heroes, villains, comedies, tragedies, twists of fate, and surprise endings, there is really only one story. One grand narrative subsumes and encompasses all the other comings and goings of every creature—real or fictitious—on the earth. Theologians call it “redemption history”; my grandfather called it the “old, old story.” (29)

Cosper recalls here not just biblical theology but J. R. R. Tolkien’s concept of “True Myth,” the notion (which Tolkien impressed on an atheistic colleague named C. S. Lewis) that all of the world’s greatest myths, legends, and fairy tales are fictitious but not false—since they echo a “true myth” that is both grand story and real history. Cosper’s powerful exposition of true myth is the fuel in the engines of The Stories We Tell, resulting in a far more illuminating and rewarding discussion of pop culture than if he were merely to hold up films and TV shows to Christian “worldview tests.”

After we understand why stories matter, we can discover how cultural storytellers have left signs in their stories that point to the One Story. Cosper uses the familiar rubric of creation, fall, redemption, and restoration as a blueprint to discuss how popular pieces of culture mirror the biblical narrative. He sees existential yearning for Eden and for home in films like The Descendants and Pleasantville; hears reverberations of Adam’s love song to Eve in the hopeful romances of How I Met Your Mother and 30 Rock; and recalls the biblical doctrine of the fall and our fruitless quest for self-determination in the stories of Mad Men. In these chapters Cosper demonstrates a crucial ability. He skillfully avoids sounding either like a culture connoisseur talking in “code” the uninitiated cannot comprehend or like an overtalkative friend retracing every scene of his favorite film while keeping you from lunch. This makes The Stories We Tell helpful for a broad audience and not just those with a personal inclination toward pop culture. Readers familiar with the shows and movies discussed will have their viewing greatly enhanced, and those unfamiliar will be able to appreciate the weaving of gospel story into such seemingly secular tales.

To put it nicely, this is not an area that conservative evangelicals deserve high marks in. For one thing, too often we have dismissed pop culture as irrelevant or sub-intellectual, unworthy of a serious Christian treatment (save for regular anathematization). Other times evangelicals have been guilty of being unable to say anything more than, “Just throw out the TV.” Now, I’m not saying that’s always bad advice; but that kind of mentality doesn’t, as Mike points out in his book, actually explain why our culture is so moved, comforted and even addicted to these pop culture mediums.

What Mike is willing to do in his book is challenge these attitudes with a different perspective: What if TV and movies have such influence in our culture because human beings have inherited, via the imago Dei, an insatiable need to understand themselves through stories?

Evangelicals don’t get to pick and choose which parts of the human experience we are going to apply the Gospel to and which ones we don’t care about. If the Good News says nothing about our need for stories, it’s less Good. Happily, that’s not the case, and you should check out The Stories We Tell if that’s good news for you.