Is Christianity fading in America? Are atheism and religious disaffiliation soaring? What does this mean for the future of American culture? Those were the questions being asked this week in light of the latest report by the Pew Center, a report which probably didn’t tell us nearly as much as its analysts and interpreters did.

The report’s content has been covered extensively and many good commentaries on it are out there. In summary, the percentage of Americans who claim no religious faith (the “nones”) is growing, and it appears to be feeding on a steady diet of ex-mainline Protestants and nominally religious. That trend seems to be the data’s clearest and most widely confirmed conclusion.

A little less widely confirmed is the state of conservative evangelicalism. The Pew researchers emphasize that evangelicalism is actually bucking a near-universal decline across other Protestant groups. Jonathan Merritt is reasonable to put those numbers in context, but his conclusion–that evangelicals are wrong and perhaps dishonest in using mainline Protestantism’s decline as an object lesson in biblical doctrine–is a non-sequitur, a nifty rhetorical sleight of hand that fixates on one metric to the neglect of almost all others, and in any case makes no legitimate counter-suggestion for why, any way you slice it, mainline Christianity was plummeting for the same years that saw evangelicalism thrive.

But not all is quiet on the evangelical front. It would be flatly dishonest to pretend that there is no serious social change in the air. The Pew Report is a useful but limited confirmation of what many social observers, religious and nonreligious alike, have seen coming for a while: An American cultural shift away from civic religion, with its shared assumptions about the common good, towards a functional civic secularism, with assumptions that were marginal in American society even half a generation ago but are now sacrosanct and often culturally (and sometimes legally) enforced.

So you have two parts of the report in something of a tension with one another. On the one end, the data confirms an emerging civic secularism and decline in casual affiliation with religious institutions. But on the other end, evangelicalism endures and even thrives, carrying with it a biblical emphasis and ecclesial centrality that is often unintelligible to those in elite and culturally powerful seats. What should we make of this?

I think the main lesson of his report is fairly simple: Christianity as a social currency is plummeting, but Christianity as a spiritual and communal way of life is rising.

By “social currency,” I mean that Christian religion is, historically speaking, as unlikely to curry favor with American culture writ large as it’s ever been. That’s not to say that there are no quadrants in America where publicly identifying oneself as a Christian will be a political or social advantage. But even those quadrants are being confronted with changes in national politics, like same-sex marriage, that challenge both Christian privilege and Christian practice.

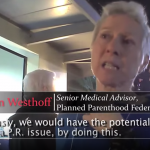

The extent to which Christian social currency is failing is a debatable thing, likely to be argued amongst people in different parts of the country and different cultural experiences. What isn’t debatable is that many people in numerous institutions, particularly businesses and Christian colleges, face an unclear future, especially if the Solicitor General’s ominous comments are any indication. Regardless, when thousands of colleges and small businesses lined up to hear a verdict on their conscience from the judicial system, sociopolitical clout is probably not peaking.

So Christianity’s social currency is low right now. But is that the end of our exploring? Hardly. As the Pew Report indicates, evangelical churches–churches that identify with doctrines like the inspiration of scripture and the necessity of repentance and faith–are flourishing. This means, I think, that as civic Christianity’s social currency evaporates, it removes the fog around Christianity as an ancient, doctrinal, ecclesial way of life.

It’s precisely this way of thinking about Christianity that has been clouded by American novelties like “Bible-Belt” civil religion and the prosperity gospel, arguably the two most politically viable forms of “Christianity” (note the quotation) on the market today. There’s been evidence for several years that both Southern, genteel, hereditary Christianity and upper-class prosperity teaching is facing severe scrutiny; consider, for one example, the remarkable numbers of millennial Christians joining Calvinistic churches, churches that preach both Testaments line-by-line and emphasize the justice and power of God. These trends point to a cavity in American spiritual culture that is being filled with an intellectually robust and unremittingly communal Christian faith–precisely the kind of Christianity that is weathering so well the changing cultural climate.

For a long time in America, Christianity wasn’t just a religion, it was a blue chip stock in culture, politics, business and education. It’s true that ours was never a Christian nation, but then, you don’t have to own something in order to influence it. It’s precisely that influence that we see diminishing. Yet as the influence has diminished, and consequently the incentive to accessorize faith, something better than influence is replacing it: Authenticity.

As C.S. Lewis once said, “Christianity, if true, is of utmost importance; if false, it is of no importance. But the one thing it cannot be is moderately important.” Moderately important Christianity is synonymous with civic religion. As long as that civic religion has purchase power in the public square, it works. But when the ground beneath it moves, it moves with it. What doesn’t move is incarnational faith, founded on eternal truth claims. And that’s the distinction we see in our religious landscape today.