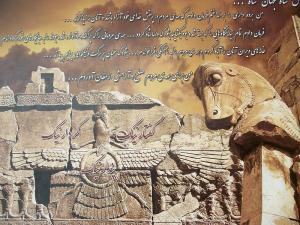

I had thought, after the previous entry, to leave Zoroastrianism behind, but then I came across this article by Martha Henriques at BBC Future on the nature of time and the reasons for its existence. This got me thinking about time in an apocalyptic sense, and I realized I could not move on from Zoroastrianism without considering one of the most obscure and controversial chapters of its existence, one in which the question of time was paramount. So, this week, we will be taking a brief detour to discuss the remarkable development in the Zoroastrian faith known as Zurvanism.

But first, I would like to offer a word or two on time and its relation to eschatology, using the BBC article as a jumping-off point for reflection. As that article notes, there is seemingly not much reason, in a scientific sense, for time to exist in the universe. Nearly all the physical laws do not require a direction in time to function, and thus time itself seems extraneous from a purely mechanicalistic perspective. And yet, time clearly exists. The article quotes physicist Sean Carroll as making the solid observation that “the directionality of time is its most obvious feature … I have photographs of the past, I don’t have photographs of the future” (qtd. in Henriques, “Why does time go forwards, not backwards?”). The sole exception to the general timelessness of the natural laws is entropy, and the article eventually decides that the reason for time’s existence is that the universe began at a state of low entropy and is moving to a state of high entropy. But the article concedes that this is rather unsatisfactory, as it opens up the question of why the universe began at low entropy and thus why time exists at all. But it requires going back to before the Big Bang, the question is one which a scientific article cannot answer.

But religion can. Indeed, given that one of its chief functions is to explain the beginning of things, it certainly seems like religion should. Indeed, the search for a proper understanding of time famously exasperated St. Augustine, who in his Confessions would make the oft-quoted observation, “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I want to explain it to a questioner, I do not know” (Augustine 242). Time, as Augustine knew, is perhaps the most paradoxical thing that humans must live with on a daily basis. It defines the shape and course of our lives. Time structures our days (and gives us a concept of “days” to begin with). The memories it leaves and the anticipations it allows form the substance of our relationships. And the fictional narratives which our society consumes voraciously would be impossible without the sequence of beginning, middle, and end and the sense of progression granted by time.

And yet, despite its ubiquity, time is impossible to get a firm grasp on. While modern science has made it fashionable to think of space and time as interlinked concepts, they are actually very different. There is a concreteness and certainty to space. If you find a favorite restaurant, you can go back to that same place again and again. If you are standing at a particular streetcorner, you can look at the street names on signs and pinpoint exactly where you are. But once a moment in time has passed, you can never return to it. And time’s constant movement means that, between when you think to look at your watch and when you do so, you have already moved past the point in time that you had wanted to know about. You can only state your position in time in a relative and provisional sense, because unlike your position in space, your temporal position is constantly moving. Time is abstract and uncertain. With time you never can quite hold onto anything, for every moment passes. With time, everything is always in flux.

Human beings, in general, do not like this. We prefer something fixed, solid, and unchanging. Perhaps this is why most humans do not really have a temporal consciousness, which is to say, they recognize the passage of time by its effects, but do not perceive its actual movement. Instead, humans generally avoid thinking of time to any greater extent than they absolutely must in order to function on a day-to-day level. This may help to explain a rather curious fact. While St. Augustine wrestled with time quite extensively, he is a notable exception among the world’s theologians. Time generally plays a minor role in religious thought. The more common attitude has been to ignore or try to escape it. Both Christianity and the philosophical monotheism that developed in ancient Greece have tended to emphasize God’s timelessness and His existence beyond the bounds of temporality rather than ponder over the meaning of time in the world He made.

And mystics have long sought to abolish time altogether as they seek a union with eternity that renders all sense of the temporal meaningless. The famous New Age author Eckhart Tolle is the most prominent modern proponent of this view. In A New Earth, he remarks, “Life is always now. Your entire life unfolds in this constant Now” (Tolle 204) and emphasizes, “Time, that is to say, past and future, is what the false mind-made self, the ego, lives on, and time is in your mind. It isn’t something that has an objective existence ‘out there’” (206). For Tolle and his ilk, time is an illusion that needs to be transcended so that the seeker may recognize the existence of a single, eternal Now. Once again, the emphasis is on finding the timeless and unchanging that exists beyond the ever-fluttering veil of temporality.

It is only in apocalyptic that we find a sustained encounter with the concept of time and a profound grappling with its meaning. Eschatology is inherently temporal in a way that most theology is not. After all, the apocalyptic genre is about the end of things. And one cannot have an end without a beginning, and a progression toward it. In that sense, apocalyptic cannot help but deal with time and its contours. But the word end has more than one meaning. It can signify a conclusion, but it can also indicate the reason for something’s existence. This is true of the end in eschatology as well. Not only does apocalypse detail how things will come to an end, but it also reveals what their ultimate purpose is. The universe’s grand finale—or the grand finale of the current aeon, in more cyclical faiths—is always the culmination either of a plan or a discernable process, one which has been ongoing since the beginning. Thus, for instance, in Christianity, the gathering of a redeemed humanity in the New Jerusalem amongst “new heavens and a new earth” so beautifully described in the final chapters of the book of Revelation represents the consummation of the plan which God put into motion at the moment of creation. All of history from Eden to Armageddon serves to lead to the final consummation of God’s plan in eternity.

While, again, not all eschatological systems necessarily resemble the Christian vision, they all emphasize that history is headed toward something. This, then, is the answer which apocalyptic gives to the question of time’s purpose. Why does time exist? Time exists because it is necessary to move the universe toward that great final something to which it is inherently directed. Frank Kermode once described works as diverse as the Aeneid and the Book of Genesis as “end-determined fictions” (Kermode 6), that is, works whose messages and narrative developments only make sense when considered from their respective cultures’ beliefs about the end that history is ultimately leading toward. But apocalyptic makes history itself “end-determined.” Things happen as they do, in the sequence they do—indeed, in any form of sequence at all—for the purpose of leading the world toward the promised end and all that it entails. Thus, in apocalyptic, time is no longer protean and ungraspable. Instead, it is made lucid and understandable because it is directed toward a definite end and thus, in pursuit of that end, achieves the kind of structure and intelligible reason for being which it would otherwise have lacked.

It is not surprising, then, that apocalyptic thinkers always seem preoccupied by time. This, again, is perhaps most readily apparent in Christianity. It is no accident that Eliade designated that faith, and the apocalyptic Judaism from which it emerged, as being marked by a unique “terror of history.” But the Abrahamic faiths do not have a monopoly on the finely tuned temporal consciousness which apocalypticism fosters and requires. Indeed, perhaps the fullest acknowledgement of time as a crucial component of eschatology comes to us not from Christianity or Judaism, but from Zoroastrianism. For it is in the Zoroastrian offshoot known as Zurvanism that time itself took on a unique and extraordinary level of significance.

Few topics in Zoroastrian studies have proven as contentious as Zurvanism. Scholars over the past three hundred years have variously characterized Zurvanism as a return to core ideas of early Zoroastrianism, a widespread heresy that threatened to overtake the traditional form of the faith and shook the foundations of empires, and as an eccentric tendency amongst a select group of overeducated Persian elites that never gained much mainstream traction. But while the reach, form, and influence of Zurvanism may be up for debate, its central belief is well-established.

Diligent readers will recall that last time, we met the protagonist and antagonist of the Zoroastrian cosmic narrative, Ahura Mazda and Ahriman. Ahura Mazda is God, the creator of the world and all that is good in it. Ahriman is God’s adversary, the corruptor of the original good creation and the progenitor of all that is evil. Zoroastrianism is unique in that it combines an abiding monotheism—Ahura Mazda, and only Ahura Mazda, is God—with a strong, participatory dualism. Ahura Mazda and Ahriman are more or less evenly matched in their struggle for control of the universe and need humanity’s help in order to shift the balance toward one side or the other. Zoroastrianism allows that Ahura Mazda is God, but He is not entirely omnipotent and must fight to purify his creation. And even though Ahriman’s defeat is destined, he possesses far more power to meddle with God’s plans than the Christian Devil can boast. In short, it is not hard, despite Ahura Mazda’s clear primacy in orthodox Zoroastrianism, to view the two entities as being something like equals.

It is from this viewpoint that Zurvanism emerges. Zurvanism presupposes that Ahura Mazda and Ahriman are entirely equal but opposing powers, representing cosmic good and evil, respectively. This complete equality and equivalence between Ahura Mazda and Ahriman makes them into something like feuding divine brothers. But the thing about brothers is that they need to have come from somewhere, from parents, in order to be brothers at all. Thus, to answer the question of how these two equal cosmic powers emerged in the universe, Zurvanism introduced a third and superior cosmic power. This being was Zurvan, the new supreme deity and the first principle out of which the universe emerged. Ahriman and Ahura Mazda were his children and had been given the rule of the universe in turn by him.

But what force could possibly give birth to both good and evil and ultimately to the universe itself? It was time. As his name, which Encyclopædia Iranica glosses as “period (of time)” (De Jong, “Zurvan”) suggests, Zurvan embodies time. In orthodox Zoroastrianism, he is a minor figure that is associated with time as marked by periods of duration. But in Zurvanism, he became the personification of eternal time, the time which had run on infinitely before the created world and would run on after it. Thus, quite unlike Augustine’s claim—echoed by modern science—that time could not be said to exist before the beginning of the universe because time is a product of change, Zurvanism instead made the whole universe itself contingent upon time, which preexisted the cosmos and was in fact necessary for the cosmos to exist.

This particular fixation on time as the foundation of the universe is also visible in the central narrative of Zurvanism, a narrative which is at once cosmological and eschatological. As Timothy J. Davis summarizes it in End of Days: An Encyclopedia of the Apocalypse in World Religions, there existed,

“a primordial androgynous entity named Zurvan who existed alone from all time. For a thousand years Zurvan had sacrificed, some say to fate, in the hope of having offspring who would assist in the act of creation of the world. Just when Zurvan was about to give up hope, both Ahura Mazda and Ahriman were conceived … Zurvan promised rule of all the creation to the first of these twins to be born. Ahriman is said to have torn open the womb of Zurvan in order to emerge before Ahura Mazda. It was originally Zurvan’s intention that Ahura Mazda be sovereign, so it was decided that Ahriman could rule for the first 9,000 years, then Ahura Mazda would reign for the rest of eternity. The world cycle would pass from origin back to origin at the End Times, in a span of 12,000 years, when Ahriman would finally be defeated by Ahura Mazda in a cataclysmic battle of good versus evil.”

(Davis 352-53)

This account gives a whole history of the universe from its beginning to its end. But the end is not simply a part of the narrative. The narrative is, itself, “end-determined.” It is Zurvan’s intention of giving the rule of the universe to Ahura Mazda, and the need to achieve that primordial design after Ahriman initially frustrates it, which drives the entire process of history. Time imposes itself on the created world specifically in order to accomplish the original aim and assure Ahura Mazda’s rule. What is more, the strong time-consciousness of Zurvanism comes out not only in the assigning of discrete periods to the reigns of Ahriman and Ahura Mazda, but also to care given to apportioning those periods out in actual numbers of years. In short, the Zurvanite cosmology makes it very clear that the world’s progression, its beginning and, most importantly, its end, all fall within the purview of time.

The Zurvanite deification of time is, as noted, quite extraordinary and unique in the history of world religions. But rather than substantially altering the basic traits of the apocalyptic genre, Zurvanism’s amplification of time instead serves to highlight features common to all apocalyptic narratives. Here again is the need to explain history as the working toward a destined end. Here is time established as the process by which the coming of that end is to happen. Zurvan may be the rare supreme deity to be entirely identified with time itself, but he is far from the only one who uses time as the prime instrument of his eschatological plan. The timeless God of the Abrahamic faiths also proves to have a significant connection to the temporal unfolding of events in his role as “Lord of History.” That the intense focus on time in Zurvanite apocalyptic so much resembles what is found in other apocalypses demonstrates just how central the concept of time is to the apocalyptic genre as a whole, and how deeply all eschatological works engage with it.

It must be acknowledged that the Zurvanites’ decision to make the whole cosmos and its deities subservient to time is certainly more extreme than what any other major apocalyptic tradition has been willing to stipulate. And some caution required when evaluating the Zurvanism as a whole, since most of the texts mentioning their beliefs come from often-hostile outsiders—the Armenian History of Vardan, for instance, offers a negative portrayal of Zurvanism because it details the exploits of its eponymous Christian hero to keep Armenia free of it. But this takes nothing away from Zurvanism’s basic insight: that time must be accounted for in the cosmic scheme of things, and the only suitable vehicle for accomplishing that is eschatology. As we look at other apocalyptic narratives, we will see a heightened consciousness of time recur again and again. As such, it will be very useful to keep the insight bequeathed to us by the followers of Zurvan in mind.

Works Cited

Augustine of Hippo. The Confessions. Trans. F. J. Stead. Ed. Michael P. Foley. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2006.

Davis, Timothy J. “Zurvanism.” End of Days: An Encyclopedia of the Apocalypse in World Religions, pp. 351-54. Ed. Wendell G. Johnson. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2017.

De Jong, Albert. “Zurvan.” Encyclopædia Iranica, 2000. ZURVAN – Encyclopaedia Iranica (iranicaonline.org)

Henriques, Martha. “Why does time move forwards, not backwards?” BBC Future, 3rd Oct. 2022. Why does time go forwards, not backwards? – BBC Future

Kermode, Frank. The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction, 1967. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Tolle, Eckhart. A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose. New York: Plume, 2006.