By now, we have an understanding of the basic contours of the messiah idea in the Old Testament. What was established in the books of Isaiah and Jeremiah recurs throughout the other writings of the prophets. Ezekiel speaks of the physical transformation of the land of Israel, “I shall make a covenant with them to ensure peace and prosperity; I shall rid the land of wild beasts, and people will live on the open pastures and sleep in the woods free from danger” (Ezek. 34:25), and of a final rescue from Israel’s many enemies, “They will never again be ravaged by the nations … they will live in security, free from terror” (Exek.34.28), along with the promise of a return of the exiled population to the vicinity of Jerusalem, “I shall settle them in the neighborhood of my hill and bless them with rain in due season” (Ezek. 34:26). The details, descriptions, and images seem almost routine at this point. There was now a common reservoir of messianic tropes which any aspiring prophet could dip into in order to stir the hearts and minds of a people in exile.

This is not to say that new and interesting ideas did not appear from time to time. Zechariah includes the prophecy that the messiah will enter into Jerusalem “humble and mounted on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey” (Zech. 9.9), an idea that would serve as the inspiration for Jesus’s own entry into Jerusalem in the New Testament. Zechariah also emphasizes the peaceful and universal nature of the messiah’s rule, “He will banish the chariot from Ephraim, the war-horse from Jerusalem; the warrior’s bow will be banished, and he will proclaim peace to the nations. His rule will extend from sea to sea, from the River to the ends of the earth” (Zech. 9:10). Admittedly, Zechariah says this while also proclaiming the destruction of the enemy nations, “The pride of Assyria will be brought down, and the sceptre of Egypt will be no more” (Zech. 9:10). Still, there is something powerful in this glimpse of the messiah as a peacemaker rather than a warrior. While not entirely original to Zechariah, the idea is more developed, and looks more like a rejection of warfare specifically, than in previous texts such as Jeremiah. Zechariah seems to credit the messiah with a policy of unilateral military disarmament in Israel, a notion which must have been as shocking then as it would be now. This, once again, is a hint of the radical scope of eschatology; if peace is to be universal in God’s endgame for history, then extreme policies like the destruction of every weapon in Israel suddenly seem far less impossible.

The statements of other prophets are often more conventional. Amos gestures toward the coming of the messiah when God promises, “On that day I shall restore David’s fallen house … I shall rebuild it as it was long ago, so that Israel may possess what is left of Edom and of all the nations who were once named as mine” (Amos 9:11-12). Since the reestablishment of the Davidic line in his person leads to the incorporation of hostile nations such as Edom into Israel, it appears that the classic warlike messiah, and not Zechariah’s more peaceful variation, who is being invoked. Though the image of the messiah as a man of peace had come into being, it clearly had not displaced the portrait of the messiah as a divine conqueror. Both conceptions, despite technically being contradictory, stood side-by-side in ancient Israel as viable and even interchangeable interpretations of the messiah’s destined future role.

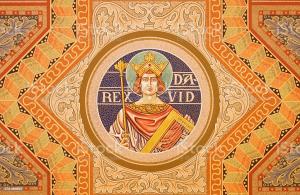

But it is the Book of Micah that offers us a snapshot of the most intriguing later development in the messianic scheme. Micah, perhaps more than any other Old Testament prophet, is at great pains to stress the Davidic character of the coming messiah. He emphasizes that, like David, the messiah will be born in Bethlehem, “But from you, Bethlehem in Ephrathah … from you will come a king for me over Israel” (Micah 5.2). After this comes the enigmatic line that describes the messiah as “one whose origins are far back in the past, in ancient times” (Micah 5:2). Christians, of course, would take this as a reference to the eternal preexistence of Christ before the Incarnation. To later Jewish audiences it is simply a promise that the messiah is of an ancient line, that of David. As for the line itself, it is gnomic and hard to decipher. But a surface reading suggests an extraordinary possibility, one which has been only briefly countenanced in Biblical scholarship. For, taken at face value, Micah seems to be saying that the messiah. since his origin is “in ancient times,” is a person who had already lived in the depths of Israelite history but who is now miraculously coming back to restore the nation to glory.

That this was a genuine interpretation of the passage, and of the messianic writings in general, is borne out by Geoffrey Ashe’s remark in his Encyclopedia of Prophecy that “A curious theory was that he [the messiah] had been born centuries before, on the day when the Babylonians burned the first temple, but God had chosen to wait before revealing him” (Ashe 149). This testifies to the reality of the belief that the messiah was someone from Israel’s distant past. And yet, the Old Testament supports another interpretation of this ancient figure’s identity, one which is much more straightforward than that which Ashe mentions in his work.

We can see it most clearly in Ezekiel’s own description of the messiah. There, the voice of God proclaims, “I shall set over them one shepherd to take care of them, my servant David … my servant David will be prince among them” (Ezek. 34:23-24). As we have previously seen Jeremiah do, Ezekiel elides the distinction of personal identity between David and the messiah until it seems as though David and the messiah are one and the same. This would typically be assumed to merely be a rhetorical flourish to emphasize the messiah’s descent from David and his many similarities to the great king. But when these passages are read in the light of Micah’s indication that the messiah is born in David’s own place of birth and its obscure reference to the messiah’s personal origin in “ancient times,” a quite different possibility presents itself, namely, that the messiah will in fact be King David, returned from the dead to redeem Israel in her hour of greatest need.

I gestured to this interpretation in my previous entry on the Book of Jeremiah, but I will now consider it here in a little more depth. The motif of an ancient king who is prophesized to return as a future national savior is a common and widespread one. It is most familiar to moderns in the figure of King Arthur, who sailed to Avalon to heal the wound sustained in his final battle and now waits in a deathless sleep until Britain faces its darkest hour. But countless other examples, both Western and non-Western, abound. The motif was applied to Frederick Barbarossa and Sebastian of Portugal in Europe but also to the Emperor Tewodros in Ethiopia and to Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl in Mesoamerica. And while scholars have long tried to find an original story to which these all can be traced back, this is unnecessary. The desire for a famous leader of days past to come back and set things right in the present is so basic that there is no surprise in its being so well-represented around the globe.

Thus, it does not seem unreasonable to suppose that the Israelites, too, developed their own version of the returning ruler motif. The Jewish Encyclopedia certainly suspects something of the sort. The authors of the entry for “Messiah” observe that, in Ezekiel, “there is an entirely new feature—the prophecy that David will be the king of the future state. As after the decline of the Holy Roman Empire the saga arose of the return of the emperor-hero Barbarossa, so, after the fall of the nation, the Jews of the Exile dreamed of the coming of a second David, who would reestablish them as a glorious nation” (Jacobs and Buttenwieser, “Messiah”). This view is founded on a logical premise. We know that, as in the case of Arthur or Barbarossa, departed heroes have been expected to return, even over vastly impossible timescales. Given this, passages such as that in Ezekiel can be read as promising that David will literally return someday. The Jewish Encyclopedia goes on to catalogue a number of further citations of the same idea in other Jewish prophets, “The hope in the return of David is expressed also in the spurious passage mentioned above (Jer. xxx. 9) and in the gloss to Hos. iii. 5 (“and David their king”), and is met with sporadically also in Neo-Hebraic apocalyptic literature” (“Messiah”). That so many authors and speakers turned to the trope of David being physically restored to Israel suggests that there was an actual belief underwriting it.

Nor is it particularly relevant whether this David was understood as the actual man or a “second David” on the model of the first. Returning ruler prophecies often fail to make the distinction clearly. Thus, prophecies of second Charlemagnes and new Fredericks coexisted in medieval Europe with promises of those monarch’s physical returns. Nor was Arthur spared from this ambiguity. Layamon, in his Brut, has Arthur himself promise to once more “dwell amongst the Britons with greatest joy” (Brut ll. 14282 but then only goes so far as to guarantee that that “an Arthur should come to help the English,” (l. 14295, emphasis mine). What is important is that a situation develops in which the prophecy has two legitimate interpretations. One is that the ancient ruler will reappear in his own person and the other is that a new ruler will embody him. Either way, however, prophecies of this sort necessarily imply a spiritual, if not a physical, identity between the past ruler and the one who is to come, suggesting that the distinction itself matters only in the material, mortal, and mundane world, not the divine reality in which prophecy takes part.

Therefore, it seems quite possible that there was some belief in King David’s physical return in ancient Israel, along with a wider sense that he would return in some form to the country, whether that be physically or spiritually. As to whether the messiah figure itself arose from the hope in a returned David, it is impossible to say. It may have been so, or the messiah ideal may have already been in existence (perhaps borrowed from Persia) and then had the hope of David’s return grafted to it. Either way, it is the figure of King David and the hope of his return (however that is to be understood) which breathes life into the Jewish conception of the messiah and gives it its distinct flavor. David became the archetype of the messiah and the model of his future career. The messianic age became, in some sense, a projection of the past reign of David into days that are yet to come.

Admittedly, this casts Judaism as being rather cyclical; indeed, it meshes well with Eliade’s theories about the return to a time of origins and the re-embodiment of heroic archetypes. But Old Testament history, with its fallings away from and returns to God and the promised land, has a decidedly cyclical element. Christianity, however, is far less so, what with the stress it places on the single, unrepeatable moment in time that was the Incarnation. Thus, the Davidic archetype, despite being so crucial to the messianic idea as a whole, was quickly shoved aside by Christianity. Christians now had a new archetype of messianic fulfillment, that being the earthly career of Jesus Christ. It was from him that interpretation was to flow backward through the messianic prophecies of the Old Testament and forward to the future time of glory. Naturally, this led to a complete reconceptualization of the messiah concept itself, a fact that does much to account for the divergence in the Jewish and the Christian views of the messiah.

Ironically, however, this developmental stage of the messiah concept is not the only time the motif of an earthly king returned from the dead. For the same thing happened with the figure who, in the Book of Revelation, emerges as the Christian messiah’s opposite number. The Beast of Revelation, commonly if inaccurately called the Antichrist, is generally accepted by scholars to be a very thinly-disguised portrait of the Emperor Nero. After Nero’s suicide, his partisans around the empire began to spread the “Nero redivivus” legend, which held that he would come again and restore the supposed glories of his reign. It is believed that this idea is what John of Patmos was taking aim at by making Nero into the future Beast, thereby having him return not as a world-saving hero but as a rapacious monster. It is, then, to a grim parody of the returning ruler motif that we owe the existence of the preeminent character in Christian apocalypse.

It seems, then, that despite religion’s best efforts to set itself up as separate from and superior to temporal power, it can never quite escape the symbols, trappings, and legacy of earthly rule. It is quite a startling to contemplate that Christ and Antichrist who engage in cosmic struggle across the pages of Christian apocalyptic may themselves both be iterations of a motif born of attachment to earthly rulers and the purely material glories of their reigns.

Works Cited

Amos. The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. 948-957.

Ashe, Geoffrey. Encyclopedia of Prophecy. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2001.

Jacobs, Joseph and Buttenwieser, Moses. “Messiah.” The Jewish Encyclopedia, 1906. MESSIAH – JewishEncyclopedia.com

Layamon, Brut. Ed. G. L. Brook and R. F. Leslie. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan, 1993. Layamon’s Brut (British Museum Ms. Cotton Caligula A.IX) (umich.edu)

Micah. The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. 963-970.

The Book of the Prophet Ezekiel. The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. 857-912.

Zechariah. The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. 985-995.