It has often been noted that great ideas have the odd tendency of occurring independently to two separate individuals at exactly the same time. Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace both worked out the theory of evolution simultaneously despite there being little contact between them. Had Elisha Grey been but a few hours quicker in filing his patent, he and not Alexander Graham Bell would be recognized as the inventor of the telephone. It is almost as though a truly transformative idea, when it wants to be born into the world, exerts such a powerful influence that more than one person cannot help but pick up on it.

Joachim’s idea of the Three Ages was as transformative in his own time as Darwin’s and Bell’s ideas have been for ours, so it is no surprise that scholars and researchers have attempted to find sources and antecedents—and if not those, at least intriguing parallels—for what he wrote and taught. Robert E. Lerner’s “Refreshment of the Saints,” which I have quoted before, was one such effort. Despite insisting that “Joachim’s position as one of the towering historical thinkers of the Middle Ages, perhaps of all ages, is unshakeable” (Lerner 101), Lerner does his best to shake it, attempting to explain away most of Joachim’s distinctive insights as inheritances from the thought of earlier theologians like Honorius Augustodunensis and Hildegard of Bingen and only barely acknowledging Joachim’s claim of new revelations and greater spiritual enlightenment as truly original.

Marjorie Reeves capably rebutted Lerner’s claims in her “Originality and Influence of Joachim of Fiore.” There, she demonstrates that while Joachim was certainly well-read in Catholic theology and near-contemporaries like Rupert of Deutz came close to his language, no one achieved the same level of originality and innovation that he did. What makes Joachim distinct from all the previous theologians Lerner cites is that, in Reeves’s words, “it is still a new stage of history which he envisions. It is not a supernatural millennium coming down from above; it is not just a ‘pause’ granted by God rather arbitrarily” (Reeves 293). It is this new sense of historical time that sets Joachim apart. He certainly made use of what had come before him. We have seen previously how his complicated reaction to Augustine in particular shaped so much of his thought. And his main source was, ultimately, the Bible; its influence on him cannot be overstated. I have previously discussed in detail how his astute attention to Revelation enabled many of his most remarkable insights. But he brought this same focus and attention to everything in the holy book. His knowledge of and engagement with the Old Testament were unparalleled among medieval theologians but he was no slouch when it came to the New Testament either. Every one of his writings, but particularly the Liber Concordie, testify to the importance he gave to every book of the Bible. And wherever he looked, he managed to rediscover long forgotten ideas that he could draw upon in his own thinking.

Perhaps he was thinking of Jeremiah’s promise of the new covenant that signifies a spiritually transformed humanity—“It will not be like the covenant I made with their forefathers … I shall set my law within them, writing it on their hearts” (Jer. 31:32-33)—when he spoke of the future “spiritual men” in whom God would work an incredible spiritual transformation. He certainly remembered Peter’s interpretation of Joel 2:28 in Acts, “In the last days, says God, I will pour out my Spirit on all mankind; and your sons and daughters shall prophesy. ” (Acts 2:17) when he promised a new development of humanity’s spiritual faculties and the revelation of previously unknown religious truths, for he cited the exact same passage as Peter had when announcing the advent of the spiritual men:

Truly because the apostles were already baptizing, the same Lord and Redeemer said: “But you will be baptized by the Holy Spirit after not many days,” thereby revealing afterward the operation of the Holy Spirit in the spiritual men who are chiefly to be expected around the end of the world-age—even if some may have already come—when that will be completed in many which was begun in a few by the promise the Lord made through Joel, saying: “It will be in newest days that I shall pour out from my spirit upon all flesh and your sons and your daughters will prophesy.” (Lib. Con. 2.1.7)

And the communal nature of the Jewish people in much of the Old Testament could have suggested ideas to him about the future people of God, just as it did to the authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Indeed, the Old Testament as a whole has quite a number of eschatological notions that differ from later Christian thought (and often from each other). Joachim’s encounter with them probably moved him toward developing a broader millennial perspective. But whenever he found suggestive passages and ideas of this sort, he responded with creativity and innovation. As much as he was inspired by the biblical texts, the insights Joachim drew from them were invariably his own. He demonstrated a perspective unlike any that had been brought to biblical exegesis before. Even at his most attentive to Christian holy writ, Joachim’s conclusions were unique and unprecedented, as were the new concepts and ideas that flowed from them. No previous Christian theologian had come close to his understanding of history as a continually evolving process through which God works His ends. That this process could culminate in the future evolution of humanity’s spiritual understanding, in an era of time known as the Status of the Holy Spirit, was an idea that began entirely with Joachim and the novel methods of scriptural analysis that he pioneered.

Thus, with not much luck in finding a predecessor in the ranks of orthodox Christianity, scholars have had to look farther afield in order to find, if not a source for Joachim’s thought, at least a convincing parallel with which to compare it. Perhaps the trend began with Henrik Ibsen who, in his great Joachimist work Emperor and Galilean, put Joachim’s teachings in the mouth of a fourth-century pagan mystic named Maximus; despite the fact that the historical figure of that name never approached anything like Joachim’s thought. Norway’s great playwright was not the last to look for Joachimism’s origins in the early centuries of Christianity. Marjorie Reeves, for all her good work in establishing Joachim’s uniqueness within the main line of Catholic thought, was not immune to this impulse. She frequently credited an early formulation of Joachim’s Age of the Holy Spirit to the second-century heretic Montanus while also suggesting that Joachim’s contemporary Amalric of Bène had developed his own version of the idea independently of the Calabrian. Neither of these claims seems to bear much weight. More recent scholars agree that Montanus’s “New Prophecy” movement was an attempt to restore Christianity to the form it had in the time of the apostles rather than the avowed forerunner of a new spiritual age. As for Amalric, all the recent scholarship I have been able to find takes for granted that he knew and was influenced by Joachim’s thought in some form. Indeed, Amalric’s example seems to rebut Reeves’s own assertion that it took decades after Joachim’s death for his thought to spread beyond Italy and for its radical ramifications to be understood.

Other scholars have ventured even further afield, turning toward Zoroastrianism—particularly in its Zurvanite incarnation—and its descendent faith, Manichaeism. These scholars suggest that the two Persianate faiths possess a three-age system not unlike Joachim’s. Zurvanism, for instance, is said to have a first age when Zurvan begins creation, a second age when Ahriman rules a broken and imperfect world, and a third when Ahura Mazda triumphs and rings in the glorious new paradise. Manichaeism is said to have a first age when light and darkness a separate, a second age in which they intermingle to form our current world, and a third age when light will finally escape from darkness and return to its source in God. However, the first and third “ages” in both of these systems include the times before our current universe’s creation and after its end. These are the “first and last things” that fall outside the scope of history, properly considered. They are not historical ages within our own world, for our world and its history only cover the middle “period.” Indeed, they are not so different in this respect from the standard Christian narrative of the universe’s prelapsarian perfection, the tragic fall of man, and the restoration of all things at the end of time. Joachim’s three ages were all within this current world’s past and future history, bookended by but distinct from the moment of creation and the final glory of the New Jerusalem. Furthermore, both Zurvanite Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism present the middle “period” as a time of degeneration, a low point between the loss of the original perfection and its eventual return. There is simply no sense of steady progress and continued evolution—albeit with a few serious hiccups along the way—that gives the procession of Joachim’s ages its unique significance.

The notion of Zoroastrianism having three periods of time probably derives from account of Plutarch (he who wrote the Parallel Lives), who wrote that the conflict between Ahura Mazda and Ahriman would have three stages:

Theopompus says that, according to the sages, one super-natural being is to overpower, and the other to be overpowered, each in turn for the space of three thousand years, and afterward for another three thousand years they shall fight and war, and the one shall outdo the works of the other, and finally Hades shall pass away; then shall the people be happy and neither shall they need to have food nor shall they cast any shadow. (Qtd. in Eduljee, “Plutarch,” emphasis original).

In the first stage, one of the two would rule for three thousand years and, in the second, the other would rule for the same amount of time. In the final stage, three thousand years when they would struggle against one another until Ahura Mazda finally emerges victorious. This at least suggests the existence of three periods of time, but it is so confused in other respects that there is little we can conclude about the nature of these three eras. We do not know whether the three periods are all confined within the lifespan of our cosmos or if they extend beyond this universe’s temporal bounds. Nor can we be sure which entity will rule which era. It is perhaps likely that Ahura Mazda’s righteous governance is followed by the evil rule of Ahriman but the opposite is also possible. We cannot even be certain that these are actual Zoroastrian beliefs. Indeed, there is good reason to doubt that they are. Plutarch was a Greek who had no direct knowledge of Zoroastrianism. All of his information comes to him second-hand from other Greeks such as Theopompus, who were often more interested in making the faith of Persia concur with Greek philosophy than with accurately recounting its theology. None of it derives directly from the Zoroastrians themselves. The confused description of the three periods and the lack of clarity regarding even the basic details of who rules what era suggests that something was garbled along the long route of transmission from Persia to Greece. No genuine Zoroastrian source suggests anything like this bizarre three-period scheme; the only thing comparable is the Zurvanite cosmic narrative dealt with above. Thus, the most probable scenario is that Plutarch is here attempting to describe the tenets of Zurvanism, but the faulty information at his disposal has caused him to unintentionally warp those tenets beyond recognition.

But if the information is genuine—and this is a big if—we can see how little it resembles anything in Joachim. Whether or not it is Ahura Mazda who reigns first or Ahriman, the movement from the first age to the second is not one of progression but one of reversal. Humanity and the world do not progress toward greater spiritual freedom and perfection; instead the whole cosmic order is inverted as good and evil succeed each other in governing the world. What is more, the final age is not at all like Joachim’s Status of the Holy Spirit. It is not a utopian era of peace, harmony, and spiritual fulfillment, as his Third Age was, but an aeon of strife as good and evil compete in brutal warfare for complete control of the cosmos. The only hope for tranquility and human happiness is in the victory of Ahura Mazda that ends this final age, not the age itself. Thus, even if the Zoroastrians believed in three temporal periods of this sort, Joachim’s formulation of the Three Ages concept was still utterly unlike anything they envisioned in regards to the unfolding of time.

Instead, one of the most important Zoroastrian eschatological texts we have, the Bahman Yašt, divides time not into three but into four ages, or at least four ages that are to occur after Zoroaster’s own lifetime. As the Encyclopædia Iranica describes it, the Bahman Yašt opens with a vision of “a tree with four branches, of gold, silver, steel, and ‘mixed’ iron, symbolizing four periods to come after the millennium of Zarathustra” (“Bahman Yašt”). Anyone familiar with Greek mythology might be tempted to associate these four ages with those of Hesiod, who saw time as divided into the ages of gold, silver, bronze, and iron, which each age declining in quality. While these two conceptions of time may have a common source somewhere deep in the Proto-Indo-European past—there is a similar four-age division in Hinduism, after all—the more immediate connection is to the prophecy of the four kingdoms found in the Book of Daniel.

In Daniel 2, the Jewish prophet interprets the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar’s dream of a statue with a head of gold, chest and arms of silver, abdomen and thighs of bronze, legs of iron, and feet of intermixed iron and clay. These represent four world-empires that will succeed each other, with each being weaker than its predecessor, until the final one is supplanted by the restored Israel of the last days. Later, in Daniel 7, he has a dream of four beasts with the same meaning. Scholars think that the four empires prophecy was a direct borrowing of the Zoroastrian four ages concept. Nor were they the only ones to do so, as the Romans also adopted it. The notion of four ages divided into four great empires had to be extremely popular and well-known in Zoroastrianism and the wider Persian cultural area for both a rather distant (and quite hostile) foreign culture and a rival faith to both adopt it and make it their own. The Romans and the Jewish people never did this with any supposed three-age Zoroastrian system. This suggests that the four ages, and not any three-age scheme, represented the dominant mode of understanding time in Zoroastrianism.

The difference in the number of ages is enough to vindicate Joachim’s originality but the Zoroastrian ages were also different in kind from his own. As for the actual content of the four-ages system, it is clear now that they were always imagined as declining in quality, with each age worse than the last. This is exactly the opposite of Joachim’s Three Ages, where each time period represents an improvement on the previous one. Narratives of temporal decline cannot be considered a source for Joachim’s own thought when he clearly saw time’s advancement as more positive and progressive that these earlier systems. The four ages also do not cover the whole lifespan of the cosmos, as Joachim’s own three do. The starting point for the sequence of four areas, whether situated at the death of Zoroaster or the birth of the first empire, is long after the creation of the world. Then there is the association of each age with a specific empire, which is completely alien to Joachim’s system. Even if some later interpretations of his work, like those found in Germany, interpreted his Three Ages in terms of specific empires, such a political theme goes against his designation of the Three Status as stages of spiritual advancement. Of course, Joachim himself knew the four-ages scheme through the Book of Daniel and would have been very aware of its popularity in Christian eschatology. That it played no major role in the formulation of his own Three Ages system demonstrates how little dependence Joachim had on any conception of time ultimately deriving from the Zoroastrian religion.

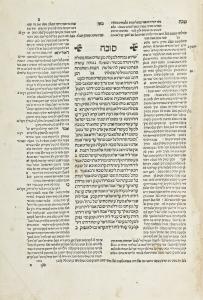

In a somewhat similar vein, Lenart Škof’s recent article, “The Third Age: Reflections on Our Hidden Material Core,” attempts to root Joachim’s Three Ages in traditional Jewish wisdom. To do this, Škof quotes the Babylonian Talmud, which states, “The world will continue for six thousand years, the first two thousand of which were a chaos (Tahu), the second two thousand were of Torah, and the third two thousand are the days of the Messiah” (qtd. in Škof 84). Škof further clarifies this in his own words, “The three ages, as propounded by the authors of the Babylonian Talmud, refer to the chaotic age before the Law, to the age of the Law of Torah, and to the future Messianic age which is still to come” (Škof 84). Relying heavily of Reeves and, through her, Lerner, Škof then tries to construct a tidy line of transmission from the Jewish sages of old to Joachim. But while Joachim’s familiarity with traditional Jewish wisdom is certainly well-known, Škof’s contention does not hold up to much scrutiny. For these three Talmudic ages seem to be largely identical with the three ages proposed by St. Augustine: ante legem (before the Law), sub lege (under the Law), and sub gratia (under grace, as provided by the incarnate Christ). Curiously, Škof seems to at least partially recognize this but places Augustine in the line of transmission between the Talmud to Joachim, despite dating the Babylonian Talmud to 600 A.D., nearly two centuries after Augustine’s passing.

For what it’s worth, Augustine’s system divided the lifespan of the world into three separate eras, but there was no sense of progression or improvement—as we have seen previously, Augustine was resolutely against such ideas. They were simply three separate ways in which God related to humanity over the course of time. Joachim knew the idea from Augustine but it did not make for a key part of the Calabrian’s own Three Ages doctrine. After all, in the earlier formulation, Joachim’s unique historical sense and his notion of each age as developing organically out of the one that came before are both absent. And, of course, Joachim would not, as the Talmud and Augustine did, identify the third age as the time of the messiah. For Joachim, the second age was the Status of the Son, ruled over by Christ as messiah. Though Christ as a central figure of the faith would not disappear from the Age of the Holy Spirit, that era was not about the figure of the messiah or His singular rule upon earth. It was a time of widespread spiritual growth where the locus of historical development would be in found not in any one single individual but in the collective body of the spiritual men (vires spirituales). This vision of the world being transformed through the collective effort of the many rather than the remarkable achievements of a single extraordinary figure was a new idea quite unlike anything either the Jewish sages or Augustine had envisioned.

It is important at this juncture to note that not every system or idea that divides time into three distinct periods is either a parallel of, source for, or inheritance from Joachim. After all, we see such divisions all around us. As noted above, orthodox Christian provides more than enough. So does our wider culture. And while I think it likely that the common manner in which we view history, with its division into the three periods of Antiquity, the Middle Ages, and Modernity, owes much to Joachim, the form that idea most often takes in popular culture, with the Middle Ages treated as an era of darkness between two eons of light, is far more akin to the Zurvanite, Manichaean, and traditional Christian schemes. What is more, each of us makes a threefold division of time every day when we speak of the past, the present, and the future, without any debt to Joachim whatsoever. While the Three Ages are the most distinctive feature of Joachim’s thought, the uniqueness of his system was not in the mere fact that he perceived the existence of three ages, but what he did with them.

To illuminate this point, it is perhaps useful to turn back to the above-quoted statement of Marjorie Reeves. The full paragraph from which those sentences were taken offers several points worth remembering in discussions of Joachim:

The crucial point here is that—however mystically conceived—it is still a new stage of history he envisages. It is not a supernatural millennium coming down from above; it is not just a ‘pause’ granted by God rather arbitrarily. It is the logical climax of the whole historical process, but because it is still part of time it does not embody final perfection. A new experience will be given, and men will live on a higher plane of spiritual understanding, but Joachim never confuses this with the illumination of eternity in the full presence of God. The tribulation of Antichrist in the Sixth Age [of the church] is to be greater than but not different from those inflicted by the sequence of tyrants throughout the Church’s history. The agents of his overthrow are seen in the main as human, though divinely aided. Because the third status is still part of history, even its life must at the last deteriorate and a final persecution of Antichrist under the form of Gog and Magog must ensue. Joachim never confuses the Seventh Day with the Eighth Day of eternity. (Reeves 293)

Once again, it is the very historicity of Joachim’s thought that makes him distinctive. The Three Status are all within time. They are all a part of time. They make up the fabric of history; it is because of them that history can progress. The world advances and evolves as they themselves do. Each age is an outgrowth of its predecessor, not a wholly unrelated entity. And as they are within history, each of them is subject to immutable historical processes; even the glorious Third Age must end with the war of another Antichrist against the people of God. But these three periods are not, in Joachim’s system, merely units of time. They also correspond to levels of spiritual insight and illumination. Thus, the procession of the Three Status is a journey of ever-increasing spiritual enlightenment, with the Age of the Son representing an increase in spiritual knowledge and comprehension from the Age of the Father. In turn, the Age of the Spirit will represent a further increase in spiritual understanding. There will be new ways and means of understanding spiritual truths and these spiritual gifts will be, for the first time, potentially open to everyone, extending the light of truth far beyond what the first two ages allowed. It is this understanding of history as a historical process and the truly transformative nature of the coming era that makes Joachim’s thought so singular and unique.

With that in mind, we can dismiss most of the parallels that have been suggested for Joachim’s teachings. For all of his reliance upon the Bible and prior theologians like Augustine, he did create a complex of ideas truly unprecedented in the history of human thought. That being said, there is one parallel which I do find intriguing. It does not predate Joachim, so his status as the first to hold these ideas remains unchallenged. But it does come from a culture and a milieu in which he could not have had any influence, thereby making it the one example of similar ideas and symbols arising independently in the human mind. Until now, however, its likeness to Joachim has gone largely unnoticed, making a discussion of this particular system all the more urgent. For if Joachim’s particular conception of the Three Ages ever did have a true parallel, it was in the distinctive eschatology that emerged within Chinese popular sectarianism over the course of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Works Cited

Acts of the Apostles. The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. pp. 1394-1430.

Eduljee, K. E. “Plutarch. His Work, Duality and the Soul.” Zoroastrian Heritage, 6 October 2011.

Joachim of Fiore. Liber de Concordia Novi ac Veteris Testamenti, edited by E. Randolph Daniel. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 73, no. 8 (1983): pp. 1-455. Translation mine.

Lerner, Robert E. “Refreshment of the Saints: The Time After Antichrist as a Station for Earthly Progress in Medieval Thought.” Traditio, vol. 32 (1976): pp. 97-144.

Reeves, Marjorie. “The Originality and Influence of Joachim of Fiore.” Traditio, vol. 36 (1980): pp. 269-316.

Škof’, Lenart. “The Third Age: Reflections on Our Hidden Material Core.” Sophia, vol. 59, no. 1 (March 2020): pp. 83-94.

Sundermann, W. “Bahman Yašt.” Encyclopædia Iranica, III/5 (15 December 1988): pp. 492-93. Online edition updated on 24 August 2011.

The Book of the Prophet Jeremiah. The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. pp. 778-847.