The transformative effect of the recent developments in sectarianism—Patriarch Luo’s teachings and the adoption of the Mother as supreme deity—is already apparent in second oldest millennialist baojuan that has come down to us, but so too is a new sophistication and complexity with regards to the Three Ages system. This text is the exhaustively-named Huangji jindan jiulian zhengxin guizhen huanxiang baojuan (Precious Scroll of the Golden Elixir and the Nine-Petalled Lotus Rectifying the Faith and Restoring the Pristine Teaching of the Imperial Ultimate for Returning to the Native Place 皇極金丹九連正信皈真還鄉寶卷), which both Overmyer and Siewert are mercifully inclined to shorten to simply the Jiulian baojuan. This book dates to 1523, a few years before Patriarch Luo’s death, and thus is a product of the crucial culture moment when both Luoist thought and the new figure of the Mother were intruding upon the traditional millennialist formulation found in the earlier Huangji jieguo baojuan. We see the results of this meet in real-time in the Jiulian, which in many ways reads like a revised version of the Huangji baojuan, updated to address the new arrivals in sectarian thought and to find a place for them in the already existing system, but still keeping the basic features of the earlier work intact.

That the Jiulian baojuan is a first attempt at amalgamating these diverse currents can already be seen from its title. Its long, formal title includes the term huangji, linking it back to the baojuan that had already laid out the sectarian system nearly a century before. The exact link between the original Huangji baojuan and the Jiulian is unclear, but it is clear that the Jiulian arose out of a common tradition or spiritual heritage as the Huangji, even if perhaps not the exact same sect. But at the same time, the title of the Jiulian also includes the term “native place,” which Patriarch Luo popularized and which was so central to his own thought. Already in its title, the Jiulian presents us with a meeting of the old and the new and an attempted synthesis of both.

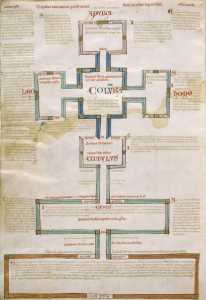

The book’s multiple allegiances also continue over into the text itself. In many respects, it follows the Huangji very closely, elaborating upon rather than fundamental reconceptualizing the ideas found there. The main thrust of the narrative is still that a compassionate supreme deity is sending down messengers to bring salvation to the people of the world so that humanity can return to its true home. Critically, this saving mission still unfolds through three ages of human history, with the new revelation being occasioned by the imminent arrival of the third age. The three ages themselves are just as important to the cosmic scheme as in the Huangji, if not more so, and follow the same basic structure. They are three periods of time under the rule of the three buddhas Dipamkara, Gautama Sakyamuni, and Maitreya, with each period moving forward the salvation process that finally culminates in the utopian future of Maitreya’s rule.

The biggest difference seems to be in the length assigned to each of the three times. As Overmyer observes in Precious Volumes, “We are told that humankind has been in bondage to samsara for eighteen kalpas, and that each buddha reigns for long periods: 108,000 years for the Lamplighter Buddha, 27,000 years for Śākyamuni, and 97,200 years for Maitreya” (Overmyer 138). This is more precise than the myriads of kalpas listed by the Huangji—and, for anyone who is interested, gives the total lifetime of the universe as 232,200 years—but the bigger change lies in the number of years relative to each other. The Huangji had the length of the temporal periods increase over time. This was presumably a sign that each age was superior to its predecessor due to the salvation process being more fully worked out and the golden era of Maitreya drawing ever nearer. The sense of forward movement and progression was clear. In the Jiulian, there is no discernable pattern to the ages; the first age, belonging to Dipamkara, is the longest, Gautama’s second age is the shortest by a considerable margin, and Maitreya’s, while nearing that of Dipamkara, ultimately falls short of it in terms of length. It is hard to say what theological point we are supposed to draw from this.

There are some other changes. Yellow enters the symbolic color scheme of the three ages, once being swapped out for the green of the First Age and once for the red of the Second—the text also sometimes swaps red and white, assigning white to the Second Age and red to the Third. Maitreya’s era is also referred to as the “Constellation Kalpa.” The Huangji had hinted at Maitreya’s special connection to the constellations, but the Jiulian begins the trend of using “Constellation Kalpa” and other such terms as a name for the new age itself. The Jiulian baojuan also puts more emphasis on referring to the three periods as yang; while the Huangji had referred to each individual age as yang, the collective designation of sanyang (three yang) apparently first appears here. The three periods are also called more specifically the Yellow Yang, Pure Yang, and Vast Yang Assembly, respectively. The symbol of the dragon flower also takes on a much greater significance, as the third age is frequently referred to as the “third Dragon-Flower Assembly,” which will be another of its usual designations going forward. But for all this innovation in terminology, however, the substance of the three ages is the same as in the Huangji. As the Jiulian says:

[In the time of] the Buddha of the Past, there was a Three[-Petaled] Lotus Assembly, in the nine kalpas of the [period of] the Limitless. The Buddha of the Present is verified by a five-petaled golden lotus, and on Mount Ling he can be seen holding the seal that matches the apex. When the Buddha of the Future appears in the world, a nine[-petaled] lotus will open and the world of bitter suffering will be transformed into a lotus-flower land. (qtd. in Overmyer 149)

Nothing here diverges from the Huangji. There are the same three buddhas ruling over the three periods. The final period of Maitreya will see the establishment of a state of universal harmony and peace, as “the world of bitter suffering will be transformed into a lotus-flower land.” Many of the Huangji’s original symbols for the three ages are also used, even as the Jiulian introduces its own unique ones. The three times are still represented by the three-,five-,and nine-petaled lotuses and with the terms Limitless, Supreme Ultimate, and Imperial Ultimate. There is a definite sense of continuity here, even for all that, at first glance, seems new.

What the Jiulian does do is clarify the process of salvation and the work done toward it in the various ages, at least to some extent. It tells us that, in the beginning, “ninety-six myriads of immortals, buddhas, celestial patriarchs, and bodhisattvas” (qtd. in Overmyer 143) descended into the barren and empty world in order to populate it but quickly became enslaved to their appetites and trapped in the cycle of reincarnation, unable to return to their celestial home. Each of the three ages is dedicated to saving a set number of these souls. As the Jiulian tells us, “At the two assemblies of the Limitless and the Great [Ultimate], four myriads and three thousand more were gathered in … Today, however, there are still ninety-two myriads … who, accepting their circumstances, have lost their true natures” (qtd. in Overmyer 143). The ninety-two remaining are to be saved in the age of Maitreya and the moments leading up to its advent. Thus, the saving work gestured to by the Huangji is clarified into a plan of salvation that sees each age saving a certain number of the lost. Certainly, the great success of the coming age of Maitreya will outshine the rather meager results of the two ages preceding it. But this does not so much denigrate the work of the previous two buddhas as demonstrate how glorious the future time of Maitreya will be, when all the world is brought together under the saving faith.

Still, there is a clear sense of progression here. The work began in the first age and continued in the second, such that four myriads and a further three-thousand individuals were saved. The process shall be completed in the third, when an unprecedented number will find salvation. Here, we are once again meet another of the uncanny parallels to Joachim of Fiore so common in the millennialist baojuans. He might not have laid out the progress of salvation in quite the same way in his works, but there was the same sense that it was a process. As with the Jiulian, it was a process running throughout historical time and all of history, divided into three ages, played a role in bringing it to fulfillment. And just as in the Jiulian, Joachim expected his third age and its lead-up to see a massive expansion in both the scope and the efficiency of the saving work—the Calabrian even dared to imagine the reconciliation of the Jewish and Muslim peoples to Christianity. We noted that, in an inchoate way, the Huangji had already hinted at these developments. But the Jiulian took those hints and expanded them into concrete details, developing the sectarian system in a direction far closer to where Joachim and his later followers went with theirs.

The Jiulian develops another characteristic feature of Huangji in a manner highly reminiscent of Joachim. We have seen before how both the Huangji and Joachim ended each of the three ages in a similar kind of apocalyptic catastrophe. The Jiulian is, if anything, more explicit on this point than the Huangji, reminding us of the systematic way in which Joachim laid out the destructive ends of his own Three Status. On the ends of the ages, the Jiulian remarks,

“for all the three buddhas, there is a time of decay and destruction, and there are disasters in each of the three apex periods … At the interchange of the three periods of cosmic time, when the kalpa is complete, the three disasters arise and disorder the sahā world (sahāloka) [= this world of rebirth” (qtd. in Overmyer 158). We know from this that each age must end, as Joachim’s did, in a similar kind of catastrophe.

This comes with a detailed description of the destruction unleashed upon the world at the end of an age. The old motif of the floating city reappears as the means by which believers shall be spared—they shall reach it by taking “a street to the clouds”—and a new, purified world emerges out of the ruins of the destroyed one. What is particularly remarkable here is the emphasis which the Jiulian places on the final destruction as the necessary and logical conclusion to an age’s lifetime. The Huangji had had the three ages each ending in destruction, but the Jiulian explicitly emphasizes that such destruction is a natural part of the three-stage temporal process itself. Destruction comes about because ages must decay “when the kalpa is complete” and the end is near, as a prerequisite for the new age to come into being. This systematic approach to the decline and end of the ages as a crucial component of the historical process is very much of a piece with Joachim, who was similarly explicit about the final tribulations of each Status being both a necessary culmination of the Status itself and central to the the wider process by which all history unfolds. The Jiulian baojuan has reshaped the entire complex of ideas laid out in the Huangji in a fashion more akin to Joachim and we shall see more examples of that a little later.

In any event, it should be clear now how loyal the Jiulian is to the earlier tradition for its understanding of the three ages and the larger cosmological framework tied to them. Where, then, do the new elements, those of Patriarch Luo’s teachings and of the Mother, come in? For Luo, it mostly comes down—as noted last entry—to matters of style and word choice. As gestured to above, the term “native place” is central to the text; it is used frequently and always describes the ultimate goal of returning to one’s original source. This comes from Patriarch Luo. But Luo’s more abstract understanding now exists in conjunction with a more concrete one which sees the native place as literally a native place, as the heaven from which all humans originate and to which they can hopefully return after death—or at the end of the age while they await the birth of the new one, whichever comes first. In addition, Overmyer notes that “a few of Lo’s terms – such as ‘majestic and unmoved’ (wei-wei pu-tung) and ‘five scriptures’ (wu-pu chung) – are also found here, though the context of their usage is different” (Overmyer 176). Luo’s terminology and something of his original ideas survive but in a new form much more suited to the preexisting millennialist mythology that Luo himself rejected.

The Mother exerts a much more overt influence. It is in the Jiulian baojuan that we have our first written testimonial to her as the new supreme deity of Ming sectarianism. Here, she already adopts the familiar persona she will have throughout the tradition, that of a concerned mother lamenting the loss of her children and wishing for their safe return. Thus, the text says of her:

The Venerable Mother

on Mount Ling

constantly looked on in hope,

longing for her sons and her daughters,

her face wet with tears,

(qtd. in Overmyer 148)

It is out of this great sense of loss and longing that she has sought to reach out to her children, sending them the message of salvation so that “they see their dear Mother and are able to realize their bodily forms of the primal beginning” (qtd. in 142). Here, as in later baojuans, we learn that she has “waited a long time” (qtd. in Overmyer 142) and that it is our duty as her children not to keep her waiting any longer.

Interestingly, the Jiulian is still indebted to the Huangji’s depiction of the Primordial Buddha as the supreme deity and reproduces it as well. He is still credited with having “put the universe in order” (qtd. in Overmyer 140) and with establishing the threefold temporal scheme, “the Ancient Buddha created the three kalpas, with three buddhas to descend and take charge of the religion” (qtd. in Overmyer 140). We are even told, “The Ancient Buddha established the teaching and preached the Dharma to benefit living beings” (qtd. in Overmyer 140). Thus, the Primordial Buddha is still both the creator deity and the one who ultimately offers the path to salvation. But then, so too is the Mother. Both are given the same dual role. And yet they are not different deities. They appears to be different names or aspects of the same entity. Faced with the Primordial Buddha championed by the Huangji and the ascendent figure of the Mother, the Jiulian simply conflates them, with the Mother now giving the somewhat distant deity of the earlier book a more human and approachable face. Overall, the basic nature of the deity remains the same but how it is visualized undergoes a striking change, as the triune godhead of the Huangji has become the mother seeking out her lost children.

That being said, the conflation between the Mother and the Primordial Buddha in this text does have interesting repercussions for how the Jiulian views the workings of the salvation process itself. Assumedly, the three buddhas must still be manifestations of the supreme deity, as they are also described as creating the cosmos:

Buddhas of the three apexes

who, for the sake of the world,

approached to take charge of the teaching.

They laid out the universe

and put the world in proper order,

with transformations unending.

(qtd. in Overmyer 155)

We are thus given a sense of how intertwined the three buddhas and their rule over the three periods is with the Primordial Buddha’s act of creation, echoing both the Huangji and in Joachim’s uniquely dynamic understanding of the Christian Trinity. In all of them, the threefold division of time reveals something fundamental about the nature of the Godhead; the tripartite structure is a natural extension of relationship of the various figures in the Godhead.

However, in the Huangji, the Primordial Buddha is also identified quite clearly with Amitabha. This is where the Jiulian departs from its predecessor, for it presents Amitabha as a separate figure from the Primordial Buddha and the Mother. What is more, Amitabha is identified with Maitreya, meaning that by distinguishing him from the supreme deity, the text mars the earlier unity that had prevailed in the Huangji’s depiction of the Primordial Buddha’s relationship to the three ruling buddhas. And this is no mere accident; as the text’s entire narrative hinges upon the distinction.

The Huangji had presented itself as a dialogue in which the primary speaker was Gautama, the ruler of the second age. The Jiulian presents itself as a dialogue in which Maitreya, the future ruler of the third is the main figure. Here, Amitabha/Maitreya describes being sent by the Primordial Buddha/Mother to bring salvation to mankind. Unlike in the Huangji, this is not a harmonious and happy case of the lord of the universe simply emanating one of his aspects for the benefit of humanity. Instead, there is real conflict here, with Amitabha/Maitreya and the supreme deity having distinct and contrasting personalities. When the Mother assigns him the task of bringing the true teaching to the world, Maitreya balks. He refuses to go, stating, “Miscellaneous teachings confuse the world, and the natures of living beings are hard and stubborn, most difficult to harmonize and put in proper order” (qtd. in Overmyer 143). Maitreya resists, drags his feet, earns the Mother’s displeasure, and is finally compelled to go by her refusal to rescind the assignment. As punishment for his obstinance, he is forced to reincarnate in the world as various religious teachers until he has earned the right to return to heaven.

The Jiulian certainly offers a lot more to entice a reader bored by theological speculations and dry discourses than its predecessor. It serves up a juicy narrative filled with conflict and dramatic tension. Its reluctant protagonist is undeniably a compelling character, even if he is one of the most unusual and uninspiring messiahs in world religion, continually complaining about his lot and making clear that he personally sees no point in his mission when “living beings in the lower realm are really difficult to save” (qtd. in Overmyer 151). One wonders how differently Christianity might have looked had been had the New Testament shown Christ frequently butting heads with God the Father over His messianic mission in the same way the Jiulian does with Amitabha/Maitreya and the Mother. But however engrossing this cosmic family drama can be, it does come at the cost of the reassurance offered by the Huangji or in Joachim’s works, where the whole of human history, for all of its deviations and disasters, is revealed to be part of a harmonious salvation plan worked out through the perfect cooperation of all the members of the Godhead.

And yet, despite this, the Jiulian’s emphasis on conflict in the divine realm does allow it to approach closer to another aspect of Joachim’s thought than the Huangji had. This involves the existence of a process of continuing revelation that begins anew in each of the three ages. This is was one of Joachim’s signature teachings—universally acknowledged to be among his most unique and astonishing—and we saw in a previous entry that the Huangji also adopted had a rudimentary form of the idea. However, it is the Jiulian that brings the Chinese formulation of the concept to maturity, shaping it into a full system of continuous prophecy more analogous to Joachim’s own vision. The vehicle by which the Jiulian is able to do this is, again, the ongoing conflict between the Mother and the messiah.

This begins early on in the text. When Amitabha/Maitreya first protests that “I cannot save the worthies and saints of the Latter Realm” and begs not to be sent on his mission, the Mother responds by citing her own travails on behalf of suffering humanity:

First I sent the immortals, buddhas, celestial patriarchs, and bodhisattvas of the three schools and five sects to descend to the world, open up new fields and plant seeds. They saved living beings in a confused fashion. Later I sent ten thousand saints and a thousand perfected ones of the “five tablets and the five titles” (wu-p’ai wu-hao) to descend to the ordinary world, to rely on the false to cultivate the true [= to begin with where people are]. Each of them received texts and relied on volumes. In the end, all this can be judged of good result only if they all reach China, recognize the Patriarch and revert to their root, and realize the gathering up of the primal ones (shou-yuan chieh-kuo). So they myriad saints pay their respects to the source, divide their schools and receive titles, complete the Way and attain perfection. (qtd. in Overmyer 144-45)

Here, the Mother counters Maitreya’s reluctance to undertake his saving mission by pointing out that she has already done so much more to save mankind than will be expected of him. Both to demonstrate how considerable her own labors have been and to emphasize the importance of Maitreya’s own mission, the Mother conveys a doctrine of continuous revelation. From the beginning of time, she has been sending messengers and prophets down to earth to bring the divine truth to humanity. Thus, in the beginning, she sent forth the “three schools” (Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism) and countless sects to spread the truth, but they were only able to do so “in a confused fashion.” When this only achieved so much, the Mother further sent forth more teachers to “rely on the false to cultivate the true,” that is to say, utilize the false beliefs of the populace to guide them toward an understanding of reality that, while still imperfect, is closer to the truth than what they believed before. But for the work to be completed and the truth to be revealed in full, she must now send forth another prophet. Maitreya is to be that prophet.

What we have here, then, is a sequence of revelations. The first ones, while valuable, are incomplete and must be supplemented by the one that is to come with the Third Age. There is a certain ecumenicalism here—not uncommon for China—in that while the three major religions and their various offshoots are not wholly true, they are divinely inspired and sent by the Mother for the purpose of beginning the work of salvation. To an extent, it brings to mind Islam’s view of its two predecessor faiths as incomplete versions of its own truth that nonetheless prepared the world for Muhammad’s revelation—with the key caveat that whereas Muslims regard the Jewish and Christian revelations as originally complete but corrupted over time, the Mother sent forth an incomplete doctrine to begin with because it is the most that people were able to understand at that stage in their development. She herself emphasizes the latter point when, after Amitabha/Maitreya again complains about the difficulty of saving souls in the world, “the Mother responds that she has prepared for this in advance by first sending down eighty-one false Amitābhas and thirty-six false assemblies for gathering together the primal ones” (Overmyer 145). Indeed, the Mother having her prophets “rely on the false to cultivate the true,” clearly draws upon the old Buddhist notion of “skillful means,” which instructs Buddhist teachers to guide people incrementally to the truth based on their current worldview rather than trying to spring a whole new doctrine on them all at once.

Still, for all of that, the similarity to Joachim is uncanny. There is here a system of continuous revelation but also a sense of progressive revelation. While the revelations in each stage of history are good and bring humanity to salvation in their own fashion, the process will only culminate with the full revelation of divine truth in the coming age. This is essentially what Joachim taught, as he says in the Liber Concordie:

Therefore because there are two of which one is unbegotten, the other begotten, two testaments were established, of which the first, as we said above, pertains especially to the Father, the second to the Son, because one is from the other. Thence the spiritual intelligence is one proceeding from both of these and itself pertains especially to the Holy Spirit. (Lib. Con. 2.1.10)

Joachim never denied the efficacy of the Jewish and Christian revelations but held that something more would be added to them through the “spiritual intelligence” in the time of the Holy Spirit. The spiritual intelligence would mark the final completion of those two previous revelations, making the whole of the divine truth known to humanity. Note as well that the process by which the Mother reveals the divine truth to humanity is threefold; there are three movements, the one of the “three schools,” the one that requires “relying on the false to cultivate the true,” and the coming one of Maitreya. This closely aligns with Joachim. He did not say that revelation had been coming nonstop since the beginning of time. Rather, it too consisted of three distinct movements in time.

The first was that of the Old Testament prophets, the second was that of Christ and the apostles in the first century of the church, and the third was the new development of the “spiritual intelligence” as a new human faculty for the Age of the Holy Spirit. After each of the first two movements, prophecy ended only to begin again as the Third Age drew near. Furthermore, Joachim carefully correlated these three periods of new revelation to each of the Three Ages, with the latter two occurring at their respective age’s beginnings. Both the stop-and-start process of prophecy and the connection between the three ages and the three movements of revelation seems are also found in the Jiulian. In this fashion, both this text and Joachim manage to convey the same idea: each of the three ages is a time of a new revelation that brings humanity closer to fully realizing the divine truth.

And much as in Joachim, the process of divine revelation for the Third Age actually begins before the age itself does. Joachim described the new faculty of prophetic insight as “the spiritual intelligence, which proceeds from the letters of the Old Testament and the New, which may be useful to us, as long as we are in this exile, that we may know what things were given to us by God” (2.1.33). These words indicate that he believed that the “spiritual intelligence” was already emerging in humanity in his own day and would prove vital in guiding the faithful through the transitional period, the “exile” that was already setting in for the faithful. Similarly, while Maitreya’s reign is in the future, the Jiulian insists that he has already begun delivering the revelations of the Third Age. As Overmyer notes:

In this scripture Maitreya has a double role, the most important of which is as revealer of the Chiu-lien book in the recent past. This scripture is his legacy, but at the same time it is described as a wei-lai ching (“scripture about the future”; chapters 12 and 17), which reveals the secrets of the Imperial Ultimate stage that is “soon to appear” (tang-lai). It is Maitreya who will usher in this new period, so his role is also that of a future savior.” (Overmyer 137)

Thus, according to the Jiulian baojuan, the major revelation of the Third Age has already been delivered at the end of the Second Age in order to help humanity through the time of transition. But it is also a “true scripture of the future” (qtd. in Overmyer 169) and thus represents the teachings of the Third Age. Having this period of revelation straddle the Second and Third Ages in this manner, beginning in one but looking over to the other, very much accords with Joachim’s own understanding of how the “spiritual intelligence” would work. But it accords even better with the claims of Joachim’s boldest and most radical later follower, Gerard of Borgio San Donnino.

As Marjorie Reeves describes it in The Influence of Prophecy in the Later Middle Ages, “the core of Gerard’s message was that, with the advent of the third status, the Old and New Testaments were utterly abrogated and authority had wholly passed to the Eternal Evangel of the Holy Ghost contained in the works of Joachim” (Reeves 60). Gerard reasoned that because the Third Age would supersede the previous two, the age itself would need a “scripture of the future” to replace the Old and New Testaments. Similarly, the Jiulian baojuan states that all the previous revelations of the first two ages will be superseded by a new scripture. Remarkably, both Gerard and the Jiulian do not claim that the new holy book will be revealed in the Third Age itself, but that it has been recently revealed as the Second Age nears its close.

For Gerard, the new scripture was Joachim’s own works, obviously written in the Second Age but looking toward the Third. The Jiulian, like the Huangji before it, saw itself as the holy book of the future. Gerard’s suggestion of a new testament to either complete or replace the Bible, made in the thirteenth century, did not gain much traction until modern times. The Huangji and the Jiulian had more luck in introducing the idea of a new scripture in their cultural milieu, as practically every later baojuan would repeat the claim. The only snag was that nearly all of them also insisted that they themselves were the actual new scripture—a reader of the baojuans must make peace with the fact that each one will inevitably proclaim itself to be singular and unique in the world while preaching almost exactly the same doctrine as all the others. Still, the fact that the baojuans latched onto an idea so fundamentally akin to that proposed by Gerard in the West is another of the astonishing convergences between the Joachimite and Ming millennialist movements.

We can also see a similar convergence in the nature of the transition period itself. Both Joachim and the Ming millenarians built upon their respective cultural traditions of apocalypse when describing the transition from the second to the third ages. Thus, Joachim spoke of the coming of the worst Antichrist at this time and drew straight from the Book of Revelation. The Ming sectarians, similarly, portrayed the changeover in their culture’s own standard eschatological terms. There is great natural calamity that rends the world, which believers are spared from by being taken to the floating city where “the little children will see their mother” when they come face to face with the Unborn Mother herself—in a strange parallel to that last point, Joachim once remarked that “the spiritual intelligence, I say, is not like a sterile man, but like a mother with her children” (Lib. Con. 2.1.34). But Joachim had also suggested something less than the complete destruction promised by Revelation, because “the spiritual men who are chiefly to be expected around the end of the world-age” (Lib. Con. 2.1.7) would work during the time of crisis and ultimately overcome Antichrist. The new world of the third age would be a continuation of the world of the second, transformed less by Revelation’s world-shattering catastrophes and more by spiritual efforts of this special group of faithful. The Jiulian, despite all its talk of the “three calamities and eight forms of suffering” (qtd. in Overmyer 180), suggests something quite similar.

Overmyer mentions that when Maitreya first comes to earth, “the savior descends to the area of Shadowless Mountain … This is … the ‘Cloud City where the Way is completed’” (Overmyer 146). This is interesting because it seems to indicate that the floating city exists not in the heavens, waiting for the time of crisis, but has been established on the earth by Maitreya already. Since there is no such physical city, this would suggest that it is in fact Maitreya’s teachings and his followers that make up the true floating city in the eschatological scheme. In this case, the believers would stay on earth during the transition, providing a safe haven from the turmoil engulfing the world around them. Thus, their place was to remain in the world, bringing about its transformation, rather than to escape to an otherworldly paradise. Siewert makes this point in Popular Religious Movements and Heterodox Sects in Chinese History, “deliverance was not conceived as escape from the three disasters and eight difficulties, but as reaching the state of completeness through the cultivation of one’s original nature” (Siewert 290); the ascent into the clouds was a metaphor for the new state of enlightenment experienced by those who would work for the new age on earth. This aligns perfectly with Joachim’s own conception of the role of the “spiritual men.” For both he and the Ming sectarians, the three ages structure was as much about continuity and progress as it was about transformation; the new world is not a new world but the old world made new by the spiritual efforts of the believers, the vanguard of the coming age.

The Jiulian baojuan ends when the Mother deems Maitreya’s crimes expiated and his mission fulfilled. Like Christ before him, he ascends to Heaven but promises that he shall soon come again to rule over the earth, “Now I am leaving, but I will return to complete gathering in those of the source. Those with good karma I will see again; together we will continue eternal life” (qtd. in Overmyer 172). Also like Christ, Maitreya would be much slower in coming than his words would suggest, leaving plenty of time for future baojuans to repeat and elaborate on the message. But the Jiulian had already done much to move the sanyang concept and the general millennialist doctrine from its rudimentary state in the Huangji into a more polished and complex form. It would do much to popularize the system as well, for Siewert notes that “[t]he Jiulian jing in particular became the basic scripture in many sects” (Siewert 292). The Jiulian’s own propagation helped the Huangji’s ideas seep into the broader popular consciousness and spread to later sectarians.

It also, as we have seen, brought those ideas further in line with what Joachim and his followers had taught in the West some centuries before. We are again left with the question of influence. Could Joachim have influenced the Jiulian baojuan at all? As I noted in our entry on the Huangji, it is possible that Joachim’s ideas, brought by Franciscan missionaries to Beijing, could have filtered down into the particular millennialist tradition that produced that work. The Jiulian baojuan, whether its author knew the Huangji or not, certainly came out of the same tradition. As Siewert remarks, “The Jiulian baojuan itself us a part of this tradition, for it speaks of the Shouyuan* zu 收源祖 (Attaining the Source Patriarch) as the saviour” (Siewert 282). Thus, it is very possible that the Jiulian, which corresponds to Joachim even more comprehensively than the Huangji did, was also influenced by him. Or it could simply be the nature of Joachim’s basic concept of the Three Ages that it tends to inspire the same kinds of ideas wherever it is found. The Jiulian could simply be an indigenous elaboration on the potentially Joachimist core of the Huangji that naturally innovated in ways parallel to what Joachim and his later followers had done in the West. Certainly, it is much harder to imagine Gerard’s belief in a new testament finding a route to China, even if he was a Franciscan, In that specific case, parallel evolution suggested by the Three Ages idea itself is likely at play.

Regardless, the Jiulian baojuan shows us is that remarkably similar processes were playing out on two sides of the Eurasian landmass, with the basic complex of ideas not only emerging but evolving in the same basic direction. It makes one wonder how much Joachim’s own teachings naturally inspire the kinds of radical thinking—like that of Gerard and the Guglielmites—that has so often been treated as a perverse twisting of his legacy. At any rate, the kinds of thinking which those later Joachimites had been condemned for in the West would find more success in China as, with the Huangji and Jiulian baojuans written and the Mother and Patriarch Luo’s vocabulary firmly grafted into the millennialist tradition, the sectarian movement of the Late Ming entered its boom period in earnest.

Works Cited

Joachim of Fiore. Liber de Concordia Novi ac Veteris Testamenti, edited by E. Randolph Daniel. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 73, no. 8 (1983): pp. 1-455. All translations mine.

Overmyer, Daniel L. Precious Volumes: An Introduction to Chinese Sectarian Scriptures from the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999. All bracketed text is original to Overmyer.

Reeves, Marjorie. The Influence of Prophecy in the Later Middle Ages: A Study in Joachimism. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969.

Seiwert, Herbert. Popular Religious Movements and Heterodox Sects in Chinese History. Leiden: Brill, 2003.