The Great Disappointment is the name given to a time when the world as we know it didn’t end. Tens of thousands of people fervently believed the date the world would change was October 22, 1844. They sincerely thought on that day Jesus would come in glory to gather the faithful to heaven before cleansing the world of sin. Many of them even gave away all their wordly possessions, donned white robes, and waited on hilltops — or in trees — for the great event. And it didn’t happen. Hence, there was great disappointment.

End-of-the-world predictions are fairly common, and occasionally some catch on with enough people that the eventual non-event becomes an event in itself. This particular non-event was one of the most famous in modern times. It’s been studied by historians, theologians, and social psychologists for clues to why this particular prediction was so compelling. Answers vary. How the non-event came to be rationalized by the disappointed has also been a focus of study.

It’s also the case that 19th century America, and to some extent Europe, was something like the Golden Age of Religious Free Spirits and Eccentrics. See, for example, “Talking With The Dead In 19th Century America” and “The Oneida Community: An Experiment In Perfectionism.” It was a time when the grip of many old orthodoxies was broken. And many otherwise psychologically normal people seemed willing to believe just about anything where spirituality was concerned. So maybe if you wanted to understand it, you had to be there.

The Great Disappointment: Origins

William Miller (1784-1849) thought a lot about religion. As a young man he rejected his Baptist upbringing and embraced Deism instead. Service in the War of 1812 left him with questions about death and an afterlife. His questions eventually took him back to the Baptists. When his Deist friends challenged his changed beliefs, he began a close reading of the Bible to look for support. And that close reading persuaded him the world was about to end.

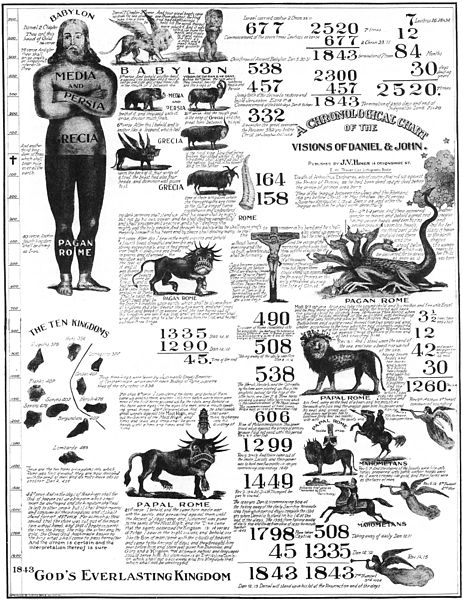

Miller began his calculations with Daniel 8:14: “And he said unto me, Unto two thousand and three hundred days; then shall the sanctuary be cleansed.” (King James Version) Miller believed this cleansing referred to the Second Coming of Christ and the cleansing of sin from the earth. And apparently there was a rule of thumb from someplace that a prophetic day equals a year. He began his calculations with the command to rebuild the Jewish Temple after the Babylonian captivity. Miller dated this event to 457 BCE. Add 2,300 years, and you arrive at 1843. Just a few years away. Miller went on to create an elaborate calendar of events to help narrow down the date more precisely.

Miller decided that the Millennium, the thousand-year rule of Christ on the earth, would begin right after the cleansing. Miller was among the first American premillennialists, a view that is mainstream in many Evangelical and Protestant denominations today, but it was new at the time. And this was about the same time that another premillennialist, John Nelson Darby, proposed the Rapture eschatology that’s become part of popular culture. Miller did not agree there would be a Rapture, or a secret snatching away of the faithful to leave sinners to suffer the Tribulation. In Miller’s view, Jesus’ return would be a much splashier event that everyone would notice.

The Great Disappointment: Spreading the Word

At first, Miller was reluctant to tell others that the Second Ccoming was imminent. He told only family and close friends, hoping that someone else would take up the task of informing the world. Eventually, however, he decided the job had fallen to him. In about 1831 he began to explain his calculations to his Baptist church members. And word spread. Other churches asked him to come and preach his eschatology to them. With practice he became a more effective public speaker.

In 1839 Miller’s movement drew the attention of Joshua Vaughan Himes. Himes was a publisher of religious works, and he had the resources, contacts, and organizational skills to spread Miller’s theories far and wide. Himes had an enormous tent made and then sent Miller and the tent on well-publicized speaking tour. He also published Miller’s theories in books and handbills. Many of Miller’s followers — who were called “Millerites” — also began to travel and preach about the great event that was about to occur. And all this preaching was covered in the local newspapers, often with great skepticism and ridicule. But it was covered.

Miller had originally proposed that the Second Coming would happen some time in 1843. Then he revised this somewhat — “My principles in brief, are, that Jesus Christ will come again to this earth, cleanse, purify, and take possession of the same, with all the saints, sometime between March 21, 1843, and March 21, 1844.” When March 21, 1844 passed without unusual incident, Miller adopted a new date, April 18, 1844. When that date came and went the Millerite movement still remained mostly intact. But when would Jesus come?

The Great Disappointment: October 22, 1844

The final date was proposed not by Miller but by Samuel Snow, one of Miller’s more enthusiastic followers. Snow’s revised calculations determined that Jesus would return on the tenth day of the seventh month of the present year. But this was using a calendar developed by Karaite Jews in the Middle Ages; I’m not sure why. And the tenth day of the seventh month of 1844 on the Karaite calendar corresponded to October 22, 1844, on the Gregorian calendar, apparently. Slowly other Millerites began to accept the new date.

By now Millerism was widespread throughout the northeastern states and into Canada. There were also Millerite groups in England. There is documentation of at least a few converts to Millerism in Australia, Chile, and Norway. As the auspicious date approached, with all the publicity, it’s possible even many skeptics were at least a little nervous. And then the day came, with the white robes and the hill and tree climbing. And it was followed by October 23.

In the days that followed the Great Disappointment, it seemed there were as many explanations for what didn’t happen as there were Millerites. Understandably, some simply walked away from the movement and went back to their original churches. But a remarkable number stayed to work out what they had misunderstood. By 1845 Millerites were beginning to coalesce around several post-disappointment Adventist sects, some of which are still with us. The largest of these is the Seventh-Day Adventist denomination, which claims about 20 million members worldwide.

I plan to write more about what we might call the Great Explanations — or rationalizations — in a future post.