Talking with the dead was all the rage in the United States in much of the 19th century. Famous mediums attracted huge, and paying, audiences who wanted to communicate with their dearly departed. And the late 19th to early 20th centuries may have been the Golden Age of Séances, in both North America and Europe.

The reasons for the heightened interest in talking with the dead are complex, but one was the rise of scientific discovery. For example, fossils were rewriting understanding of the age of the Earth, making it much older than the Bible suggested. Although certainly science and religion had butted heads before, by the 19th century more people were literate and educated enough that science couldn’t be easily dismissed. But science then wasn’t quite what it is now. Strange as it might sound to us today, many educated people of the period embraced séances and other means of talking with the dead as “scientific” proof of life after death.

The 19th century also was a time of heightened religiosity and new means of religious expression. The Second Great Awakening was underway in the U.S. when the 19th century began. The first Swedenborgian church in the U.S. opened in Philadelphia in 1817. Joseph Smith began the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1820. The Oneida Community flourished from 1848 to 1880. The Seventh-Day Adventist Church emerged in 1863. Jehovah’s Witnesses began witnessing in the 1870s. Madame Helena Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society was founded in New York City in 1875. Mary Baker Eddy built the first Christian Science church in 1894. These are just a few examples of the new religious movements of the time. The spiritualist movement was also a religious movement, albeit one without much in the way of organization.

About the Spiritualist Movement

Spiritism or spiritualism is, very basically, a belief that there can be communication between the living and the dead. Although accounts of people talking with the dead go back to ancient times, the modern spiritualist movement is said to have first emerged in the 1840s in Hydesville, New York. What began as a prank by two teenage sisters, Maggie and Kate Fox, turned into a career. The sisters found “spirits” in their home that made rapping noises in answer to questions. The adults were amazed; word got around. And when Maggie and Kate moved in with their sister Leah in Rochester, the rapping apparitions moved with them.

In truth, the Fox sisters had figured out how to make cracking noises with their joints without anyone realizing where the noise was coming from. It was clever, and with Leah’s help it became a business. Soon the Fox sisters were “talking to the dead” in front of big, paying audiences. Of course, many people accused the sisters of fakery, but many more believed them. The show went on until 1888, when a repentant Maggie confessed to the public.

But by then, mediums had become an entertainment phenomenon. Just a few examples: In the 1850s brothers named Ira and William Davenport were a sensation with what was, essentially, a magic act in which the “magic” was attributed to unseen spirits. The Davenport’s act involved bells, ropes, musical instruments, and trick cabinets. It sounds like a first-rate magic act, at least. Another medium named Eva Carrière was famous for regurgitating “ectoplasm” while in a trance, which seems a lot less entertaining to me. And in the 1890s a medium named Ann O’Delia Diss Debar (among her many other aliases) produced “spirit paintings,” new paintings by the ghosts of dead masters. So, yes, we’re talking big-time flimflam here. But I understand some mediums (probably not the better publicized ones) sincerely believed they were talking with the dead.

Spiritualism and Religion, North and South

As with many things, the spiritualism movement functioned differently in the northern U.S. than it did in the South. Spiritualism was most common in New England, where it was something of its own religion. The mediums were laywomen and men who were not associated with a specific denomination. If there was serious objection to spiritualism coming from organized religion at the time, however, I haven’t found mention of it.

Note that the original feminist movement emerged in New England at about the same time as spiritualism. And the majority of mediums were women. Some historians consider spiritualism to be connected to feminism. Being a medium was one of the few professions of the time in which women had authority.

In the South, spiritualism became attached to evangelicalism. Preachers didn’t ususally hold séances but often passed on messages from the dead at revivals and prayer meetings. There were also traveling mediums who would set up shop in local Masonic Halls and contact the dead for a small fee.

Talking With the Dead

In 19th century America, infectious diseases like cholera, typhoid fever, diphtheria, and scarlet fever could decimate communities like a swinging scythe. Two out of ten children died before the age of five. And then came the U.S. Civil War, 1861-1865. Considering that it’s estimated about a quarter of American men under the age of 30 were lost in the war, there were probably few Americans, north or south, who didn’t know a soldier who hadn’t come home. Since they died away from home their families were especially eager for reassurance and closure.

Those who grieved turned to mediums or attempted séances on their own. It’s estimated that in the late 19th century as many as 11 million Americans — roughly 28 percent of the U.S. population at the time — engaged in serious attempts to contact the dead. For a time there were countless books and periodicals on spiritualism in circulation.

The Art of the Séance

Mary Lincoln’s famous White House séances may have helped popularize the practice. Mediums who held séances in their own parlors could produce marvelous effects with hidden wires and floating balloons. The “tilting table,” moved by wires usually controlled by the medium’s foot, was a common feature of the séance. These theatrics were especially effective in candlelit rooms; séances and newfangled electric lights did not mix well.

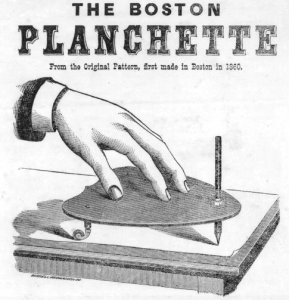

The “dead” could respond to questions by knocking as participants spelled out words. They would also respond in writing by means of a planchette, a small board on casters that held a pen. The planchette was placed on paper, and then people put their hands on the planchette as it wrote messages on the paper. Eventually someone thought to have the small board point to letters of the alphabet instead, and the Ouija or spirit board was born.

Americans who believed in spiritualism included William James, one of the fathers of modern psychology. Newspaper editor and publisher Horace Greeley promoted mediums in the New York Tribune. Mark Twain and Frederick Douglass attended séances. Late in the 19th century the séance craze spread to Europe. Queen Victoria used séances to speak with her beloved Prince Albert. It’s on record that Marie and Pierre Curie attended séances. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of the logical Sherlock Holmes, was a firm believer in spiritualism. Conan Doyle not only attended séances but also spent much of the last years of his life lecturing and writing about talking with the dead.

Spiritualism continued to be popular after World War I and the terrible Spanish flu epidemic of 1918. But by then people were catching on to the hucksterism attached to it.

How the Movement (Mostly) Ended

Spiritualism met its greatest foe in the American master magician Harry Houdini (1874-1926). The Great Houdini recognized a parlor trick when he saw one. He tirelessly investigated and publicly exposed how mediums performed their “special effects.” He told a congressional committee, “This thing they call Spiritualism, wherein a medium intercommunicates with the dead, is a fraud from start to finish.” Houdini’s biographers say he wanted to be remembered as the scourge of hoaxes even more than as an illusionist and escape artist. “For Houdini, a man who’d made a living suspending disbelief with skillful, innovative illusions, Spiritualist mediums transgressed both the ethos and artistry of his craft,” Bryan Greene wrote in Smithsonian magazine (“For Harry Houdini, Séances and Spiritualism Were Just an Illusion,” October 28, 2021).

In the 1920s the magazine Scientific American offered a cash prize to anyone who could produce a spiritualist phenomenon, or “visual psychic manifestation,” that couldn’t be debunked. Many mediums, including famous ones, entered. The prize was never awarded. At the same time, some Christian denominations became more vocal about denouncing “the occult.” Eventually most educated and “scentific” people no longer wanted anything to do with it.

Although spiritualism never completely disappeared, it faded away in the 20th century and moved to the back burner of popular culture.