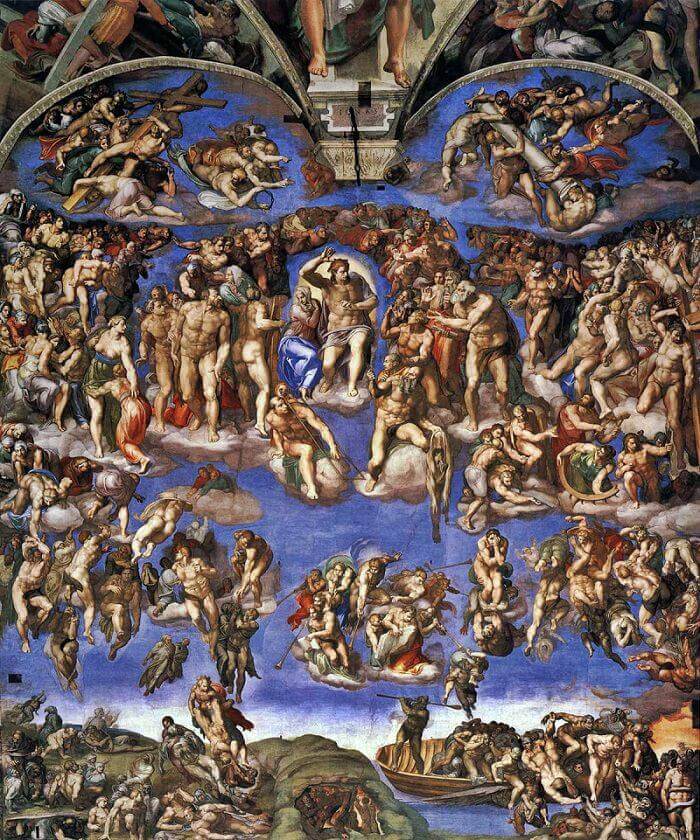

All of the world’s major religions are, to an extent, eschatological. Because one of the primary functions of religion is to provide a comprehensive and understandable explanation of the world, both the beginning and the end of all things—or, at the very least, the beginning and end of the current order of things—must be accounted for. As Frank Kermode observes in his 1967 classic The Sense of an Ending, ““Men, like poets, rush ‘into the middest,’ in medias res, when they are born, they also die in mediis rebus, and to make senses of their span they need fictive concords with origins and ends, such as give meaning to lives and poems” (Kermode 7). As Kermode observes, beginnings and endings have a way of giving order and meaning toward life. Thus, religion, that ultimate vehicle of meaning-making, has found accounts of the beginning and the end indispensable. And because the basic facts of human survival require us to always keep one eye toward the future with all its possibilities and challenges, the end of things in particular must always loom large over religious thought.

But even given this basic fact, Christianity stands out for its particularly strong emphasis on this eschatological aspect. If all religions foresee an end to things—or, again, an end to the current cycle of things—Christianity is unique in the attention and importance which it places on the end. Indeed, so important is the world’s last bow in Christianity that Christian terms for it, such as “apocalypse,” “Armageddon,” and “doomsday,” have all become standard in the modern, secular lexicon for talking about the end of the world. This particularly strong relationship was noted by no less an authority than Mircea Eliade, who proposed that Christianity inherited a particular “terror of history” from Judaism and then proceeded to amplify it in the person of Jesus Christ. As Eliade observes in Cosmos and History, “We must remind ourselves that, for Christianity, time is real because it has a meaning—the Redemption” (Eliade 143). For Eliade, the fact that Jesus’s salvific career on Earth took place as a singular and unrepeatable historical event naturally forced early Christianity to adopt a distinctly linear perspective of time. Time was no longer the steady state of periodic renewal that Eliade saw in all other premodern societies. Now it came from somewhere and it was going somewhere, with the middle parts simply being the journey from one point to another. And despite the old truism that “the journey matters more than the destination,” defining life as a journey naturally focuses the mind on that final moment of arrival.

This means that, for Christians, the eschaton—the end-times period when the current world order shall cease and God’s plan will be completed—is now. Christians are thus living, every day, at the end of the world. To have such an understanding of one’s own position in time must completely reshape one’s view of oneself and the world. It did so for the earliest Christians and this fact goes a long way toward explaining the extreme self-sacrifice they displayed, both in their willingness—hunger even—for martyrdom and their unceasing appetite for mortifying the flesh. It also did so for many other notable Christians throughout history—with results ranging from the laudatory to the infamous. But it is safe to say that most Christians do not and have not shared the same immediate sense of living at the end of history. This is by no means a criticism. After all, if Christ’s death and redemption rung in the final days, then the final days have been going on for just about two-thousand years or so. If God is in process of rolling up the world, He is certainly taking His time with it. Most humans can only wait so long before their expectations start to shift, and Christians have collectively been waiting longer than most.

What is more, other religions have at times proclaimed the coming of the awaited savior. Inevitably, when history refuses to end or progress in the direction promised by this advent, the movement falls apart or dwindles to a few persistent souls on the margins of society. Christianity alone, when confronted with the disappointment of the world’s failure to be reborn in the wake of its messiah’s coming, did not shrivel or shrink in this fashion. Quite the opposite. The more that the time of Christ and its transformative, messianic promise receded into history, the more dominant Christianity became, first within the bounds of the Roman Empire, then in Europe, and then across the globe.

Because no other resolutely eschatological faith has ever conquered the world like this, none has had to wrestle with how to maintain itself in what is essentially a suspended eschaton. Only Christianity has had to figure out how to continue on in the long span of time between when the fulfillment of history was achieved and when it will finally be made visible. And the solution has been, for the most part, to blur the fact of the initial fulfillment all together, or to interpret it in strikingly different terms. At the risk of offering an overly rigid simplification, it could be said that most of the major developments of Christianity and the crises it has faced can be traced back to the fundamental tension between the eschatological promise at the faith’s heart and the need to smother than promise in order to maintain a viable and enduring religious superstructure when the promised transformation refuses to come.

Over the next few weeks, I intend to explore the eschatological promise at the heart of Christianity in greater depth and examine its ramifications throughout the history of the Christian Church. By so doing, I hope to prove that this sense of fulfilled eschatology—and the accompanied sense of an eschatology promised but not yet fulfilled—is what most fully defines Christianity as a religion. But I also aim to suggest something about our modern religious climate, namely, that much of mainstream Christianity’s current malaise stems from its inability to minister to an era wherein daily life itself has become apocalyptic and that this defect could be remedied by a better understanding of the restorative eschatological promise at the heart of the Christian message.

Works Cited

Eliade, Mircea. Cosmos and History: The Myth of the Eternal Return, 1954. Translated by Willard R. Trask, New York: Harper & Row, 1959.

Kermode, Frank. The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction, 1967. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.