The Book of Revelation, also simply called the Apocalypse, is one of the most famous books of the Bible, for better or worse. How much of a surprise it must be for moderns, then, to find out that in the Middle Ages, there was another Apocalypse. And how much of a shock to learn that it was the one attributed not to John of Patmos but to Methodius of Patara that enjoyed the greater degree of acceptance, circulation, and influence. But this is exactly what occurred. It is true that the Apocalypse of Methodius was never quite canonical but, given that the Book of Revelation’s own status within the Biblical canon was just as ambiguous and murky during these centuries, that was no very great roadblock toward popular acceptance. And Pseudo-Methodius was very popular indeed. Particularly in the Byzantine East but also in the Latin West, it displaced Revelation for centuries to become the account of what was to transpire in the last days.

Another surprising fact about Pseudo-Methodius is just how influential this text is on global literature beyond the apocalyptic genre itself. Many narratives and ideas about history and religion that later became standard in medieval Christendom—and some which still hold resonance to this day—originated in or were given canonical form by Pseudo-Methodius. Here we find the account of Gog and Magog’s imprisonment by Alexander the Great, and the claim that the Antichrist will hail from the tribe of Dan. And while the narrative of Solomon and Sheba makes no appearance, Pseudo-Methodius’s frequent and strangely persistent claim that the Last Emperor would be a descendant of the Ethiopian royal line creates an association of that dynasty with messianic potential that would blossom into the national myth of Davidic descent found in the Kebra Nagast, an idea which has shaped the history of Ethiopia like no other. Yet, for all that, it is still in the figure of the Last World Emperor that Pseudo-Methodius offered its greatest contribution to the history of thought.

Despite the Emperor’s importance, however, the Syriac prophet shows no particular hurry in getting to him. For, as it unfolds, the Apocalypse of Methodius turns out to not be simply a tale of the end-times, but of all time. True, the end is Pseudo-Methodius’s predominant interest, but it is clear that the author feels, if the events of the end are to be properly understood, everything that precedes them must be understood also. And there is a lot that precedes them. The Pseudo-Methodian prophet believes, according to the biblical proclamation that “in the Lord’s sight one day is like a thousand years and a thousand years like one day” (2 Peter 3.8), that the seven days of creation could be interpreted as referring to seven thousand-year periods that together constitute the whole history of the world. The idea was not new; it goes back to St. Augustine and was a commonplace in medieval thought. But few texts would show as much of a commitment to the exact delineation of the ages and the careful charting of their central events as Pseudo-Methodius does.

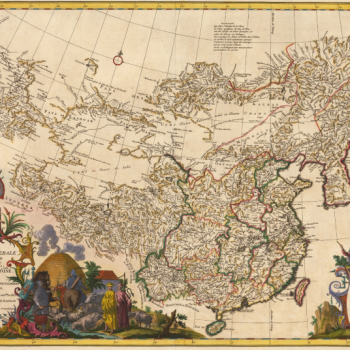

But there is a guiding principle to all this, a north star that leads Pseudo-Methodius steadily on and keeps this prophet from getting lost in the flows and eddies of history. That north star is the concept of monarchy, specifically the formation and progress of the monarchy that God has chosen to rule the world. Much of the early work concerns itself with the formation of the world’s first kingdoms in the murky period after the Flood that Genesis only glances at. Thus, we learn that, “In the 790th year of the third millennial period, Babylon the Great was founded and Nimrod reigned in it. And afterward the sons of Ham chose a king for themselves from one of their own, whose name was Pontipos” (Pseudo-Methodius 3:6). Jonitos, a son of Noah, had already “ventured into the East as far as the sea in which the rising of the sun occurs (3:4)” and built a kingdom, in what may be the first systemic attempt to introduce the East Asian cultural sphere into the Biblical scheme. Pseudo-Methodius informs us that “[t]hese therefore were the kingdoms that appeared first on earth and after them all peoples began to establish kingdoms for themselves” (3:8). The feuding and warfare of these new-born kingdoms lays the groundwork for the strife among nations that would prevail into the Methodian prophet’s own day and, indeed, into our own.

From there, Pseudo-Methodius provides a royal history of the world. It is a strange read as far as a book with pretensions to Biblical status goes; the nation of Israel figures relatively little and Alexander the Great shows up a bit too much. But this is all in service of proving a single point: that the Roman Empire is God’s chosen nation and destined to rule the world until its end. This is justified in various ways. One is to claim Ethiopian descent—albeit with Italian and Greek roots thrown in for good measure—for the Roman Emperors. On one hand, this gives the Roman Emperors a claim to the three major Christian areas of the day (the Latin West, the Greek East, and Ethiopia) and thus to universal rule over all Christians. On the other, it allows Pseudo-Methodius to add a veneer of Biblical legitimacy to his claim by citing the line, “Ethiopia will stretch forth her hands toward God” (9:8), from the 68th Psalm. The text also argues that since the True Cross erected on Golgotha is in Roman territory—apparently the Pseudo-Methodian prophet believed it to still be standing there, some six centuries after the Crucifixion—demonstrates that the Roman Empire is under the protection of the Cross, “What sort of person either could or would ever be able to overcome the strength of the Holy Cross or comprehend its power? Thus indeed does the dignity of the Roman Empire possess reverence, mighty through Him who was hanged upon it, our Lord Jesus Christ” (9:9). All this serves to prove that the survival of the Roman Empire into the end times and its universal rule is the divine and unchallengeable will of God.

This too must be shocking to most modern Christians, who are no doubt aware that it was the very empire that the Pseudo-Methodian prophet is now calling Christ’s own that hanged Christ from that cross in the first place. Those familiar with the Biblical Book of Revelation will no doubt be dismayed to see the Roman Empire turned from the vehicle of Antichrist’s reign to that of Christ Himself. Pseudo-Methodius is full of strange and shocking contradictions like this, such as in one passage where the prophet attempts to prove that God’s earthly kingdom has never been defeated by citing first the victories of the nation of Israel against the Egyptians and Canaanites and then immediately afterward citing that nation’s own destruction by the Roman Emperors Titus, Vespasian, and Hadrian. Throughout the text, this prophet goes to considerable extremes to paint the Romans in the light of God’s favor and ignores or brushes away any Biblical depictions to the contrary.

His reasons for doing this, however, are not merely to produce pro-Roman propaganda. It is true that the Roman Empire was still very much in existence, at least in its eastern, Byzantine form. And it is true that the Apocalypse of Methodius is propaganda. But it is propaganda of a different sort that the merely political. For the Pseudo-Methodian prophet finds himself writing at a time of crisis. In very recent history, either in this prophet’s own lifetime or very soon before it, the political order of the Middle East had been completely transformed. The Caliphate, the political expression of the new religion Islam, had swept away all before it, completely swallowing up the old Persian Empire and driving the Byzantines out of Africa and the Levant. Whether or not he found himself living under Islamic rule, the Pseudo-Methodian prophet was certainly writing at a time when Christianity itself was on the ropes in the region and no one knew where the Caliphate’s rapid expansion would reach its limit.

This was enough to convince him that he was living near the end of history and that the end-times were near. The broad overview of history and the careful chronology he had offered throughout the text was to prove that in his own time (about 670 A.D., give or take a decade or two), the world’s allotted seven thousand years were nearly up and apocalyptic events were being set in motion. Indeed, the Islamic invasions were themselves apocalyptic events, in the proper sense, for in the newest millennium, or the seventh then taking place, in the same time the kingdom of the Persians will be annihilated” (11:1), signifying that the end of the days was on the horizon. Of course, this meant that Pseudo-Methodius’s understanding of the age of the world differed markedly from that of modern Biblical “literalists” and young-earth creationists. But then, Christians have always dated themselves by the end and not the beginning.

Still, Pseudo-Methodius’s message is not one of despair, but of hope. This prophet does not want his (Christian) audience to give up, not even at this late date in the history of the world. This is where his portrayal of the Roman Empire as God’s chosen kingdom comes in. The prophet reminds his readers of the line about the “restraining force” in Second Thessalonians: “Who therefore is the one [to be taken] ‘out of the way’ [of Antichrist] if not the empire of the Romans? For all the sovereignty and authority of this world will be destroyed apart from her … And she will persist, until the last hour shall come, and she ‘stretches forth her hands toward God,’ and according to the saying of the Apostle: ‘when all sovereignty and universal authority shall be destroyed and the Son himself shall have surrendered the kingdom to His God and Father.’ What sort of kingdom? Obviously that of the Christians” (10:2-3). Since the forces of Islam are not the Antichrist, Pseudo-Methodius assures his audience, they will not destroy the Roman Empire and the “kingdom of the Christians.” Rather, that shall continue to endure a little while longer, even if the time until Antichrist’s advent is rather short.

But the shortness of the time and the need to push back the invaders necessitates that the final emperor and its heroic savior from current peril must be one and the same. So far, it is easy to see why the Pseudo-Methodian prophet made the steps he did. But nothing required him to make the Emperor into such an awe-inspiring, titanic figure. The Emperor only had to be heroic. Pseudo-Methodius makes him godlike. His career is described in a rather truncated form, as he first appears in the thirteenth of the book’s fourteen chapters, but the author fits a great deal into this short span and the brevity, if anything, gives the Emperor’s story a kind of energy and dynamism missing from other parts of the text.

The Emperor arrives on the scene suddenly. Pseudo-Methodius introduces him into the action with this statement: “Then suddenly distress and hardship will spring upon them [the forces of Islam], and the King of the Greeks, or namely, of the Romans will leap upon them in a great rage and he will awaken just as a man does from a drunken stupor, he whom men supposed to be dead and useful in nothing” (13:11). The Last Emperor, called “King of the Greeks” or “King of the Romans” throughout, literally leaps into the pages of the story. Who he is, where he came from, and how he ascended to his throne, and any other hints of identity or backstory are completely omitted; he seems to come into existence with that fateful leap. The only clue that Pseudo-Methodius gives us is that the Emperor was considered useless and believed to be dead. But this gnomic clue does not help us much. We do not even know how literally to take it. Was the Emperor really believed dead, and thus considered useless for that reason? Or was he a useless person who, on account of his seeming incompetence, was considered “as good as dead.” It is impossible to know. However, the first interpretation, that the Emperor was someone really believed to be dead, would cast a long shadow over the European imagination, with a presence that can be felt, in some quarters, to this day.

But the main effect of this passage is not to highlight the Emperor’s undeath. It is to emphasize his speed, fury, and lack of identity beyond his holy mission. He is the sword of God, and the Pseudo-Methodian prophet would rather have us think about the sword’s fierce strikes than about the materials of its composition. Thus, his struggle against the Caliphate is portrayed as a lightning campaign; he marches up from “the sea of Ethiopia” (13:11), storms into the heart of the Arabian peninsula, and secures a quick capitulation. His glorious victory and the complete dismantling of the Caliphate is accomplished almost before it had begun. The Emperor is not merely the protector of Christians but is also the instrument of God’s wrath and, as Pseudo-Methodius repeatedly emphasizes, while God’s wrath kindles slowly, when it is at last explodes, it does so suddenly and with overwhelming force.

But the Emperor is more than just a vindictive warrior-zealot. That he is, certainly—upon winning the war, he imposes a “yoke upon them seven times greater than their yoke was upon the earth” (13.13)—but after victory, another side of the Emperor is revealed, that of benevolent, peaceful monarch. After the Emperor has defeated his foes and claimed unchallenged dominion over the whole world, “then the land will be pacified, which had been made desolate by them, and each person will return to his own land and into the inheritance of his fathers … And men will be multiplied over the earth, that had been made desolate, just like locusts in multitude” (13:14-15). Thus, there will be a restoration of what was lost. People will return to their homes, reclaim the property and inheritance that is rightfully theirs, and a human population boom would ensure the repopulating of places emptied by war and tyranny. But this peace is also more than simply a restoration to an earlier, preferable state. In fact, it excels all earlier states of human happiness. As Pseudo-Methodius says: “And there will be peace and great tranquility upon the earth, of such kind as has not yet arisen nor shall the like arise until that the newest day at the end of the ages” (13:15). The peace of the Last Emperor’s reign will be greater than what has ever been known or what can ever be known until the end of time, when the new heaven and the new earth come into being. In short, the Emperor’s reign represents the most perfect time in human history, when the earth is almost transformed back into the primordial paradise.

That is not to say there are no bumps along the way. Gog and Magog break loose of their prison in the north in order to disrupt this peace. But they only manage to besiege a single city before meeting their end when “the Lord God will send forth one of the commanders of His army and he will slay them in a single moment in time” (13.21). They do not even come face to face with the Emperor himself before their destruction. Since the war with Gog and Magog had been foreshadowed in the text since the time of Alexander, this scene feels like a bit of anticlimax. But it does demonstrate that the Emperor’s reign is so peaceful and so successful that even the ravages of Gog and Magog seem like nothing more than a blip in the radar. After Gog and Magog’s defeat, the Emperor establishes Jerusalem as his capital and rules there for ten and a half years.

So far, the Emperor has proven to be quite an effective messiah-figure. He has rescued the faithful from the grasp of their persecutors, defeated the enemies of Christianity, and established a universal peace that is like nothing that has ever been seen before. These are all things Christ is expected to do in the standard Biblical account but here, with the Emperor doing such a good job, Christ hardly seems needed for human salvation—on a material level, at least. But ultimately, Pseudo-Methodius’s Emperor must succumb to the same logic that had created him in the first place. For if the injunction of Second Thessalonians had seemed to suggest his necessity, it would also suggest his inevitable failure. After all, the “restraining force” had to be removed for the Antichrist to come. Thus, the Roman Empire must fall when the time of Antichrist has finally come. And, by virtue of being the Last Roman Emperor, Pseudo-Methodius’s glorious “King of the Greeks and Romans” must personally endure that downfall. His life must end in tragedy in order that the through-line of apocalyptic prophecy can be preserved.

And so, when the Antichrist appears, manifesting suddenly in Galilee, the Emperor’s fate is sealed. The Emperor recognizes that the tide of events is against him and takes his leave from this life in one final, sweeping act: “And when the son of perdition has appeared, the King of the Romans shall ascend upwards to Golgotha, wherein was fastened the wood of the Holy Cross, in the same place where the Lord endured death for us. And the king shall remove the crown from his head and lay it upon the cross and extend his hands toward heaven and surrender the kingdom of the Christians to his God and Father … And just as the cross is lifted upward into heaven, the King of the Romans will likewise immediately surrender his spirit. Thence shall all sovereignty and authority be destroyed, that the son of perdition may appear visibly” (14.2-6).

It is a striking, powerful scene, one of the most poignant in all apocalyptic literature. But it does serve a purpose. The Emperor placing his crown upon the cross signifies the surrender of all earthly authority to God. Thus, not only is the “restraining power” of the Roman Empire formally removed but the Antichrist’s reign, which follows immediately after this, is established as illegitimate from the start, since legitimate monarchal authority is gone from the earth. But even more than that, the Emperor’s action brings full circle what had begun with Nimrod, Jonetos, and their ilk. They had begun the practice of making kings while the Emperor ends it. By giving royal authority back to God, the Emperor demonstrates that such authority was always in God’s hands to begin with, not in his or that of any of the other worldly figures who have either inherited or elevated themselves to royal rank over the course of the narrative.

This final verdict on monarchal authority is fascinating for how much it seems at odds with the prevailing pro-monarchy tone of the text up until this point. But we shall discuss that, other matters of interest, and a consideration on the origins of the Last Emperor figure in the following entry.

A Note on Sources

For the quotations of Pseudo-Methodius found above, I have relied upon the Latin version of the text found in the Dumbarton Oaks edition edited by Benjamin Garstad (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012). While I have supplied my own translations of the select passages quoted above, I have prepared them in consultation with Garstad’s own translations of the Greek and Latin texts, silently removing and correcting a few mistakes and elaborations in the Latin text in order to more properly get at the basic form of the Syriac original.

The quotation from the Second Letter of Peter comes from, as always, The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992). “The Second Letter of Peter” covers pages 1544-46.