So everybody’s talking (well,instapundit.com for one, and other blogs, too) about and linking to Christina Hoff Sommer’s article in The Atlantic, “How to Make School Better for Boys; Start by acknowledging that boys are languishing while girls are succeeding.” She summarizes many of the arguments in her book (girls are outperforming boys at all levels of schooling, and going to and completing college at rates far higher than boys), and highlights programs within and outside the United States that have addressed this problem, either incidentally or intentionally.

The solution that’s being adopted is a return to vocational education (or, in the new terminology, CTE, Career and Technical Education) — partly as an alternative to and partly as a supplement to sitting in the classroom, boys are given opportunities to work with their hands, not just in a traditional automotive repair class, but learning computer repair and networking, refrigeration, and other skills. And this engages them and improves their performance not only in these fields but in their overall schoolwork as well.

She also claims (I hadn’t heard this before) that one of the causes of the demise of vocational education is not just our national fixation on attending college, but the aggressive push for “gender equity” — the heavy hitters among feminist and other such groups focusing their energy on getting girls into shop class and ultimately effectively taking the approach that “no CTE is better than sex-segregated CTE” in terms of the consequences of their actions.

What are, exactly, the consequences? If we’ve been talking about alternatives to college and whether marginal kids are wrongly being steered to college when they have no idea what they’d do, maybe it’s not such a bad outcome for fewer boys than girls to attend college. The bigger question is how this impacts their earnings — and here Hoff Sommers links to a Brookings study on men’s earnings over time. Here’s the key chart:

Full-time male workers’ earnings have bounced around erratically, and all men’s earnings have dropped substantially over the past generation, with a few rebounds.

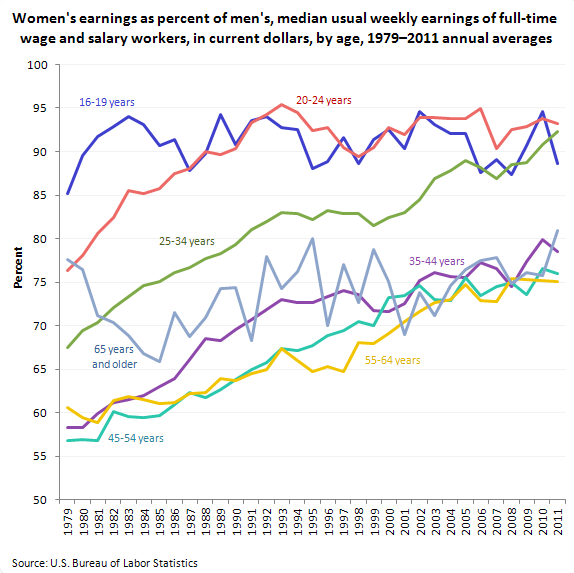

I tried to find the equivalent table for women’s earnings; irritatingly enough, all I could find at the BLS was women’s relative earnings, here:

which is interesting in its own right: the 16-19 year olds’ earnings and the 20-24 year olds’ earnings have been bouncing around at between 90 – 95% of men’s for a fair while, and the 25-34 year olds’ have been steadily and dramatically rising for the duration of this chart. To a certain degree, these results seem almost too good, given all the reasons women’s wages can be lower than men’s, including working fewer hours (e.g., at the bottom of the 35+ hours per week rather than the top end), residual effects of extended time out of the labor force, and choice of lower-wage careers (social worker rather than chemical engineer).

In any case, looking at the source data, I came upon this table, in a PDF (which I couldn’t get to copy over well):

Table 5. Median usual weekly earnings of wage and salary workers, by hours usually worked and sex, 2011 annual averages

Total, 16 years and older:76.2%

1 to 34 hours:105.2%

1 to 4 hours:96.8%

5 to 9 hours:107.0%

10 to 14 hours:101.8%

15 to 19 hours:102.6%

20 to 24 hours:109.4%

25 to 29 hours.105.1%

30 to 34 hours:108.3%

35 or more hours: 82.5%

35 to 39 hours:109.9%

40 hours 88.4%

41 or more hours:86.8%

41 to 44 hours: 86.1%

45 to 48 hours: 91.1%

49 to 59 hours: 90.5%

60 or more hours:85.9%

Unfortunately, the table doesn’t provide data on the number of men and women in each group, of the sort that you’d need to calculate, via a regression analysis, the amount of the male/female wage differential that’s explained by hours worked. (Or maybe “fortunately” is more appropriate, as I’d have to then admit that I don’t remember how to do this any longer.) But, still, this is pretty remarkable.

Anyway, where was I?

Here’s a story from my own extended family: girl gets pregnant at 17. She has twins, but the local daycare, whose owner is a friend of the family, cuts her a break on tuition while she works there, and defines “work” very loosely to enable her to get her high school degree. She’s praised as having her head on straight and doing a great job, given her situation. Dad, age 18 when he got his girlfriend pregnant, dropped out of high school to support the young family, but wasn’t able to get much of a job. He wasn’t doing too well in school in the first place, and even flunked the aptitude test when he tried to join the Marines. He broke up with the girlfriend after a while, and now works cleaning/emptying out foreclosed houses. Future unknown.

(I’d tell you about my own boys, but they have issues of their own and are not “typical boys” by any means. I will tell you that, at the parochial school they attend, enrollment has dropped considerably, and my 1st grader’s class is the smallest yet, and disproportionately boy — which could be chance, or could be a disproportionate number of parents of boys fearing that they’d struggle at the public school.)

Another memory: when my children were babies, and I was home on maternity leave or on my days off on my part-time schedule, the TV was on fairly often, as a bit of company, while nursing the baby, for instance. And the number of commercials for various “colleges” — Westwood College of Business, or a culinary school or fashion design school, or for video game designing or general IT professionals — was astounding. I came to the conclusion that the target audience was a large pool of high school graduates who were watching daytime TV without the foggiest idea of what to do with their lives, except for maybe some part-time job.

It shouldn’t be a zero-sum game. We, as a society, can’t afford to ignore our boys any more than our girls.