A: Only that in the latter case, society or the government or your favorite advocacy group agrees with you that your life isn’t worth living.

I’m typing quickly, because I have to start my workday ASAP, but I wanted to comment further on a couple new articles on the Brittany Maynard case.

First, an article in The Atlantic, “Brittany Maynard and the Challenge of Dying with Dignity,” which observes that “most terminally ill people who seek assisted suicide are depressed. But depression also makes physicians less likely to prescribe the lethal medications that would allow terminally ill patients to die by their own hand,” due, that is, to (in addition to doctors’ own ethics) the legal requirement that a doctor may not prescribe the poisonous pills to a patient with an underlying mental health issue that may itself be the cause of the desire to die.

And, according to the article, the profession is doing a better job of self-policing than in the Netherlands, say, where

the country has recently made forays into offering physician-assisted suicide to psychiatric patients, rather than just to terminally ill ones. In 2013, the psychiatrist Gerty Casteelen helped kill a healthy 63-year-old man who was dreading his retirement.

But the article implies that there’s something “unfair” about this requirement, because it hinders people from obtaining the pills. Its final paragraph:

There are a number of questions prompted by Maynard’s death, but one of the most troubling is, what happens when the patient seeking lethal medications isn’t as bright, purposeful, and tranquil as Maynard was? How do we know if someone, besides being ravaged by their body, is also tormented by their mind? And should it matter?

The comments are also worthwhile to read, because there are a number of readers who are willing to go further, such as TheMcAlisterShow:

I hope that, in the future, people stop seeing depression as a “complicating factor” that disqualifies someone from being allowed euthanasia, but as a valid reason in-and-of-itself to commit suicide.

Obviously, the decision should never be taken lightly, but I feel like demanding that people stay alive for decades when they are constantly suffering, on the off-chance that they might miraculously experience a newfound zest for life, is one of the cruelest, most sadistic things in the world.

A person’s body and life belongs to no one but themselves—and if suicide was a legally available recourse, then people could warn their families and friends in advance, and die peacefully, with no mess and no trauma for whoever finds them.

And Doctor Greybeard provides the reply to the question in my title:

There is a big difference between “clinical depression” and what some have called “rational dysphoria” which is being unhappy with good and observable reason, like being terminally ill. I think physicians who are concerned and deny euthanizing drugs to “depressed” patients have little experience with the latter, and often mistake it for the former.

Second article — actually an opinion piece in the Chicago Tribune, “The lessons of Brittany Maynard” (behind a paywall, but you can google the quote below), which actually takes the step of connecting “suicide where society agrees with you” and “suicide where society doesn’t”:

But the Maynard case, and the issue it illuminates, distracts from a larger and less controversial one. She chose to end her life with the help of a doctor to escape a difficult death from cancer. A staggering 40,000 Americans committed suicide in 2012 by means of their own devising — and the number has risen steadily since 2000. More people now die annually from suicide than from auto accidents.

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention says the vast majority of those who kill themselves are in the cruel grip of mental disorders, including depression and schizophrenia — and most had not had treatment for these problems in the previous year. Many of them, it’s safe to say, could have been saved with timely, appropriate care.

Are these really two separate issues? Can society really engage in suicide prevention for one group of people while endorsing it for another, based on the premise that “suicide is OK if you get permission from us first”?

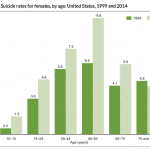

A quick look for suicide rates indeed makes it clear that suicides are increasing. Here’s some data from an article in the New York Times, “Suicide rates rise sharply in U.S.”

From 1999 to 2010, the suicide rate among Americans ages 35 to 64 rose by nearly 30 percent, to 17.6 deaths per 100,000 people, up from 13.7. Although suicide rates are growing among both middle-aged men and women, far more men take their own lives. The suicide rate for middle-aged men was 27.3 deaths per 100,000, while for women it was 8.1 deaths per 100,000.

The most pronounced increases were seen among men in their 50s, a group in which suicide rates jumped by nearly 50 percent, to about 30 per 100,000. For women, the largest increase was seen in those ages 60 to 64, among whom rates increased by nearly 60 percent, to 7.0 per 100,000.