The actuary in me insists on getting the math right; the historian in me insists on getting the history right.

Here’s a follow up to my post a couple days ago about “unmarriageable” poor men.

The left tends to say the reason why marriage rates have dropped among the poor, and among poor blacks in particular, is that, in our postindustrial economy, men without education are no longer able to get factory jobs that can support their families in the way they once were. I would dispute that the majority of black men were ever routinely able to get these sorts of respectable factory jobs; maybe, at best, this was true for a brief moment in time, between the migration northward and the decline in factory work. So: simplistic and wrong understanding of history => wrong conclusions (at best, “we need a massive government hiring program”; at worst, “poor men are simply never going to marry, so the state’s role in taking care of poor women is unchangeable and we’d better accept it and adapt with the times”).

The right, on the other hand, says, people have been poor throughout history, and the poor now are really far better off materially than in the past. Yet, in the past, marriage rates were much higher than today, so this is culture, not economics. And this is probably true in a very limited way. But when we take this further and say, “poor families in the past supported each other stuck with each other through thick and thin,” I think we’re missing the mark. Yes, the lower class in the United States today has a greater living standard than the middle class* a century ago (*this is clear, at least, with respect to farm families, though I’m not really sure about the urban middle class then, where I think there was far more of a gulf, but I’m not sure), but there was still a lower class then, with its fair share of dysfunctionality: after all, Prohibition didn’t come out of nowhere, but because there was a real issue with poor men drinking away their wages, then coming home to beat their children, and, no, I don’t believe this was just in middle-class women’s imagination.

I paid a visit to the basement books-in-exile shelves and found a book I had read many years ago, City of Women, by Christine Stansell; it was published back in 1987, when “women’s history” was emerging as a field of study. She studied women in New York City from 1789 to 1860, and particularly their changing work experiences, from domestic work, to the world of the factory. And she does indeed report that, among the poor/working class women she studies, wife-beating was common, and drunkenness, and husbands abandoning their families — but, then, her major sources for this are criminal court records and the records of almshouses/charities, so the work-a-day families, where husbands and wives live harmoniously and put food on the table more often than not, would be hidden from view, showing up neither in criminal cases nor charity pleas.

But in any case, we make a mistake if we think that, prior to the 60s, every white family was the Ingalls, and every black family the Logans (that is, from Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry).

Did changing cultural norms simply mean that the marriages that never happened would have been bad marriages anyway? I don’t know.

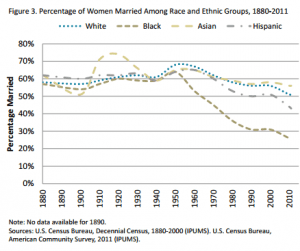

But let’s look again at the graphic from my prior post:

again, with apologies for the lack of detail as this is from a report and I couldn’t find the original, historical data online (again, here’s the link to the original source) — I could find marriage rates going back to the 50s, at census.gov, but not the fuller series to 1880 that would really help with patterns before the decline.

For what it’s worth, from census.gov, among whites, marriage rates (that is, percent of people ages 15+ who are married) from 1950 to the present, peaked in 1960 at 70% of men, 67% of women (showing the impact of men’s lower life expectancy), and dropped gradually but steadily to 57%/55% in 2010.

Here are the rates for blacks:

Men Women

1950 64% 62%

1960 61% 60%

1970 57% 54%

1980 49% 45%

1990 45% 40%

2000 43% 36%

2010 39% 33%

The footnotes at the site (downloading the first table) specify that the 1950 and 1960 data is based on ages 14+, so it’s a bit understated relative to the later years; in addition, these years count all non-whites as “black” so, again, it’s not apples-to-apples. But look at the drop-off from 1970 to 1980, and the widening gap between men and women, which points to an intermarriage component as well as widows.

What do you make of this? In the first place, don’t misread this: this doesn’t say that only 33% of black women will ever marry, but reflects some never marrying, others marrying at a later age, and still others marrying and divorcing. You can also combine this with tables on age at first marriage. And this data also doesn’t fit with the table above, which shows a more rapid drop-off (perhaps due to this data set being all nonwhites for ’50 and ’60?) and lower ultimate rates as well.

And that’s about as much as I’ve got for you for today. Your thoughts welcomed in the comments.