I have just a few minutes before I have to start work, but I want to say a few more words on the whole business of — arrgh, I can’t stand the propagandistic label “Dreamers”, so let’s say Unauthorized Minor-Arrived Residents, even though UMAR doesn’t roll off the tongue very easily.

First of all, these individuals have no legal right to stay here. The whole premise of DACA was that these people are of a class that’s a low enforcement priority, and that the government, when it makes that declaration of deferred deportation, can also hand out work visas. The program did not promise anyone anything other than a two year period of deportation relief.

Do they have a moral right to stay here? Or, put another way, is it morally wrong for the government to deport them?

There’s not a simple answer.

On the one hand, the government, in having failed, for years and years, to take any substantial enforcement action against illegal immigration, enabled the current situation — of individuals who have lived here since childhood — to come to be. That’s on them, and on all the voters who returned these men and women, who spoke words of welcome instead of providing for enforcement, to office.

But on the other hand, it simply cannot be that we establish the moral, if not legal, right of residence for anyone who arrives before reaching the age of majority. If that is the case, that it is morally wrong to deport someone who arrived before age 18, then there’s no reason why that should hold true only for those who came before 2007, is there? If we establish that as a general principle, then we also establish as a general principle, open immigration, albeit with a second, informal track, in which living with false identification and forged proof of work authorization, is considered no more wrong than, say, driving 26 in a 25 mph zone: sure, it’s on the books, but it’s not really wrong, because you don’t intend for anything bad to happen.

That is the fundamental reason why “Dream Act” opponents say that there has to be some increase in enforcement at the same time, because otherwise we’re establishing the general principle of open immigration for minors; even if the specific law in question contains a limit, the rhetoric does not.

If, on the other hand, the law providing amnesty also includes, say, a mandatory e-verify, or tracking and expulsion of visa overstays, or something similar, than at least we’re moving a bit closer to expressing the notion that, purely out of generosity, we are giving these young adults the gift of legal residency.

And the larger issue is that there are simply too many politicians and activists who simply see nothing wrong with illegal immigration, who truly do view it as simply an alternate pathway to entry into the United States. Remember that Jeb Bush famously described it as an “act of love” because these people were motivated by the desire to provide for their families, and Cardinal Cupich, shortly after arriving in Chicago, praised illegal immigrants for all the ways in which they are employed (under the table, or with false IDs, but I guess that doesn’t matter) in the U.S., and spoke of legalization as a top priority. We’ve got Rahm Emanuel and Bill De Blasio and other mayors and governors touting their support of illegal immigrants, promoting local ID cards, working with banks to enable them to get mortgages, and so on.

In their view, illegal immigration is simply a fact of life; if you’re willing to live in the United States under conditions that are somewhat tenuous and require low-paying jobs, because the better-paid jobs require authentic work authorization and English-language fluency, then they assume that you have a “good reason” in the form of dire poverty at home, so that we in the United States have an obligation to welcome you, and, somewhere along the way, after a certain number of years of paying your dues this way, you’ll have a moral, if not legal, right to stay.

But consider the end result of such a de facto immigration pathway: as the wave of illegal immigrants who came following the Reagan amnesty age, they will not be eligible for any form of retirement benefit. Three years ago (the only useful item in a google search), NBC News featured the plight of these individuals, who continue working well past what we consider “retirement age” and never expect to stop. Perhaps their numbers are smaller than NBC paints, because the largest number go back to Mexico to retire with a house built from funds sent back there year after year; I don’t know. But accepting illegal immigration as the normal state of affairs means a future generation of retirees without resources, relying only on what they can earn or receive in support from family. And, sure, proposals for amnesty would remedy this — but only with more government spending as these people become eligible for Social Security, SSI, food stamps, and so on.

And — sorry, this is getting a big rambly — the answer that’s touted is simply to provide amnesty a heck of a lot sooner in the process, or to achieve a “one and done” amnesty solely by increasing the numbers of immigrants admitted into the U.S. to such a degree that any would-be illegal simply arrives in the proposed legal pathway. But this has it’s own set of issues, given the massive number of new immigrant spots we’d need to provide one to everyone who wants to come.

So it’s not that easy.

Readers, ramble along with me in the comments. What do you think is to be done, in the long term?

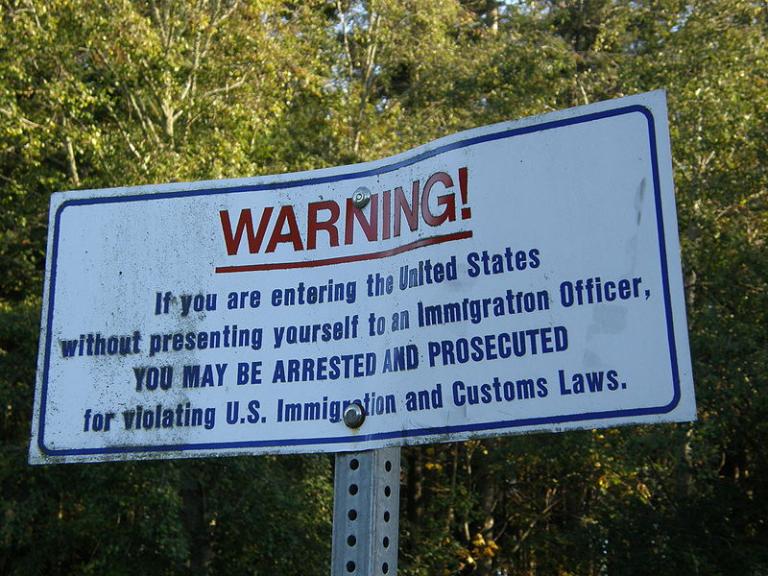

Image from wikimedia commons