The graduate students at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign are striking. Not the STEM students working in labs on grants, but the teaching assistants who work running discussion sections for the large lecture courses, or teaching introductory classes. They are upset that, in the new contract, the university proposes to remove the rock-solid guarantee that, once provided with a tuition waiver, students will keep that level of waiver except for cases of poor performance. What’s more, they are asking for 8% immediate, then 4% annual raises for the remainder of the 5 year contract, a more generous health insurance benefit, and subsidies for child care. This is a big, big ask, for a university that is struggling to keep its tuition level in order to keep its enrollment stable, in the face of large numbers of students leaving Illinois and its budget crises in the dust (though, to be sure, their situation isn’t as perilous as other Illinois public universities, where enrollment drops have been devastating).

For reference, the existing contract provides for pay of $16,281 for a half-time (20 hour/week, 9 month) work appointment, plus 24 vacation days, if appointed on a 12-month basis, 13 sick days, and subsidized health, dental and vision benefits. As an hourly pay rate, this works out to about $21 per hour.

How does this compare with college professors, or, more precisely, the sort of non-tenure-track, non-research instructors that they’re most closely comparable to? Could a university simply hire more non-tenure-track instructors (or non-research-track) instructors? Cost-wise, it might be a wash, when you compare the salaries for grad students, adjusted to full-time basis, and add in the tuition grants and the time professors spend supervising their TA work (assuming they provide such supervision rather than leaving them to their own devices).

Conveniently enough, the entirely faculty’s salary is available online, and the salary that lecturers earn seems to start at $43,000, and going up as high as about $55,000 for senior lecturers. If you assume that they likewise work on a 9-month basis, then their pay (not considering any ancillary benefits) is about $10,000 higher than the pay of grad students.

It’d be better for the students, to have experienced instructors, rather than learning from grad students who are themselves just figuring out for themselves how to lead a discussion effectively, or what grades to assign to papers. (The Math Myth had a heavy dose of criticism for universities using T.A.s for math classes, boosting the degree to which students would struggle to learn the material.) It would remedy the imbalance between grad students and jobs available, by reducing the former and increasing the latter. And it would save the university money, assuming that the net cost of the tuition waiver exceeds $10,000.

But is grad student education a net “cost” for a university? One suspects that there would be significant pressure from the professors themselves to retain a graduate program in their departments, and keep it at its current size, because of the benefits they receive — it’s preferable to teach a small graduate student seminar than a large undergraduate class, for one, and having graduate students to advise and whose dissertations one supervises, is a benefit in that it bestows prestige and recognition, as well as being, among the job responsibilities, one of the more attractive ones. It would not be easy to get professors to accept replacing graduate student-related activities with undergraduate teaching, as long as they have the power, within the university’s governance structure, to prevent it, or as long as they are able to “vote with their feet” — that is, if a university feared an exodus of professors, unless a move to replacing at least some T.A.s with instructors were to occur fairly uniformly across the nation’s universities. If a university can’t feasibly reduce its graduate programs, then it’s a whole different story altogether.

Which suggests that it’ll be much more difficult for universities to evolve than to be replaced by other teaching models.

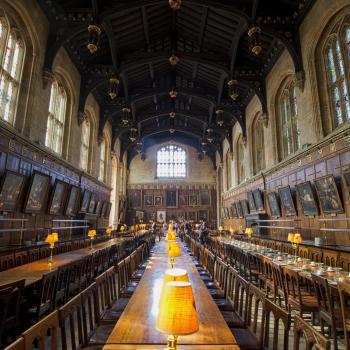

Image: a teacher’s strike. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AFair_Contract_Now.jpg; By Brad Perkins (Flickr: Fair Contract Now) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons