So last weekend, when hubby and the boys were all at a Boy Scout outing, I took advantage of the warm weather and the museum “free day” to go to the Field Museum.

It’s a funky sort of museum in that it’s a combination of a true “natural history museum” (dinosaurs, animals) and what the Europeans would call a “museum of ethnology” — and my interest generally lies in the ethnology side. (The evolution/dinosaurs display has a recreation of a prehistoric rainforest which frightened my then-preschooler when we attempted to view the exhibit some time ago; since then, I went back and walked through the whole thing but it wasn’t the sort of thing that I wanted to return to again and again.)

In particular:

the museum has a substantial display on Africa. It starts with a feature about a holiday in Dakar, Senegal, then takes you to the Bamum and Tuareg cultures, explains metalworking in Ethiopia, and so on, with various artifacts. (There’s also a section on animals and the environment, which I skipped.) It’s quite nice, even though it’s also getting a bit long in the tooth — that is, the “family in Senegal” part has black-and-white photographs where it seems it could be easily updated, since it’s not meant to be historic but present-day.

What I hadn’t remembered was that after viewing all these exhibits, you end up in a section on the slave trade (explaining that Africa was vulnerable to European colonization because of the loss of its people through slaving) and the life of slaves in the Americas. I am inclined to think that this was new, though I can’t say for certain. At any rate, it didn’t really seem to fit — it was no longer “ethnology” but American history (for which, to be sure, there is no dedicated museum in Chicago, only the Chicago-specific Chicago History Museum and the African-American-specific DuSable Museum).

I then walked through parts of the Ancient Egypt exhibit, which always strikes me as something of an anomaly in the way it displays actual human corpses, but since these are “mummies,” we think of them as somehow “not real people,” I guess. But the exhibit is an interesting combination of mummies and information/artifacts related to this, and a considerable amount of information on daily life.

Up next: I went upstairs. I skipped the “Abbott Hall of Conservation: Restoring Earth” and the website certainly indicates I didn’t miss much: videos and photographs and “hands-on learning tools” which generally mean computer displays, no? The Tibet display seemed smaller than I remembered it and — grrr — the Cyrus Tang Hall of China appears to have upgraded the exhibit on China at the costs of requiring an additional ticket, making it the second “extra charge” permanent exhibit at the museum (the first being a children’s exhibit about bugs). Why this, of all the exhibits, requires an extra charge, isn’t clear to me. Is it as simple as supply and demand and expecting that, as the newest exhibit, people will choose to pay the upcharge ($8 for adults, or $6 if you’re upgrading from one ticketed exhibit to all) so that this is a revenue boost win?

At any rate, I continued on to the Regenstein Halls of the Pacific. Unlike the African and Egyptian artifacts, which were just acquired in an anonymous sort of way, here the exhibit starts with a story: in the early 1900s, one man travelled throughout the Pacific islands collecting objects: masks, wood carvings, instruments, and the like. We are told that he bought them with trade goods such as machetes. And it really is a massive collection, with explanations of what the rituals were in which the objects were used.

Now, that’s only half the exhibit — the other half is, quite honestly, much less interesting, featuring a bit on the geological history of the islands (volcanos, etc.) and some bits about present-day occupants (a recreation of a Fiji market).

Then it’s back downstairs, and then, well, it all gets a bit Woke, with the Robert R. McCormick Halls of the Ancient Americas. As an incidental comment, the entire display of the, well, non-Ancient Americas (except the Northwest Coast & Artic Peoples) is being completely re-done. It’s not a surprise, I guess, given that this was one of the oldest parts of the museum, and the last time I was there, consisted of display cases with clothing, tools, etc. But the emphasis now seems to be on “people think that Indians disappeared and we are still very much here,” and, quite honestly, if the exhibit becomes focused on modern day life, well, a bunch of video clips and text with a sort of idealized picture of native culture would, let’s face it, be of interest to very small numbers of visitors. (And, what’s more, this emphasis on “people think we no longer exist, but we do” strikes me as a bit weird. The Ancient Egypt exhibit has no interest in telling us what life is like for modern Egyptians, for example.)

But anyway, back to the Ancient Americas.

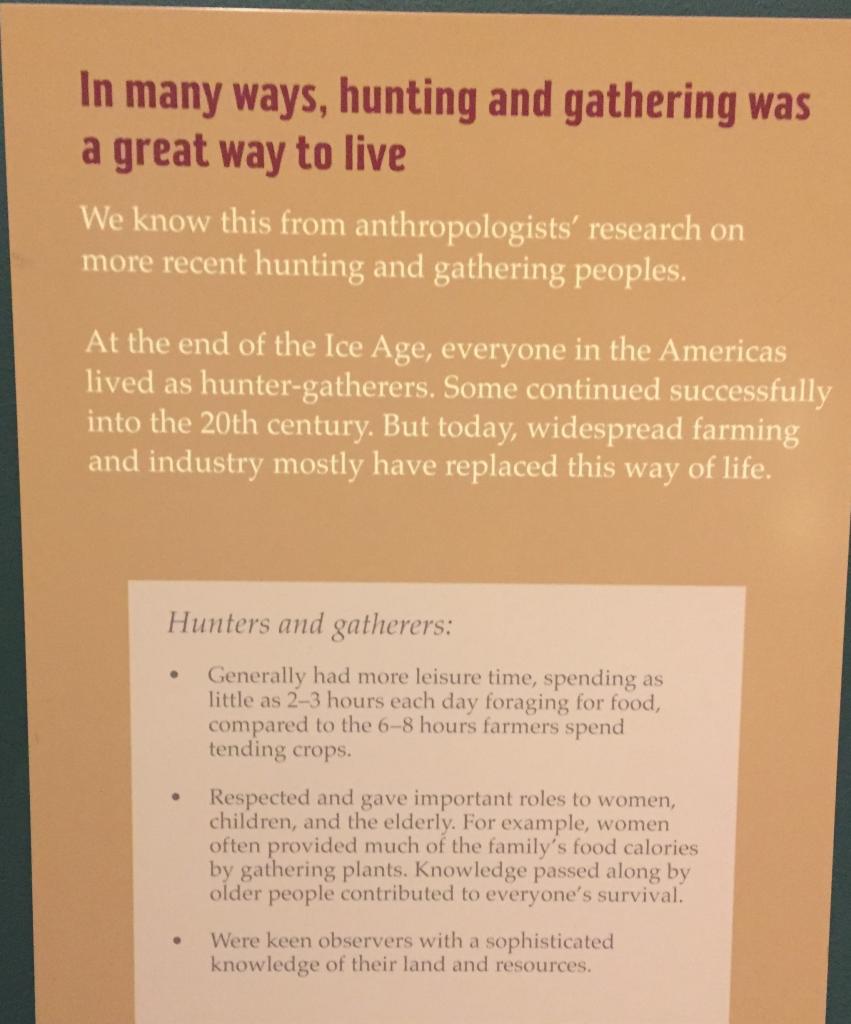

The exhibit is organized based on the development of societies into increasingly more complex communities, from the first archeological signs of arrowheads, to the development of farming, pottery, villages, and then eventually to empires. And here are there bits of text:

Was hunting and gathering “a great way to live”? This display tells only a small part of the picture. Farming became widespread for reasons other than just the stupidity of those who invented it. The notion that hunters and gathers “respected” children misses that, to my understanding, infanticide was common if a woman gave birth and still had a child who needed to be carried as they moved from place to place.

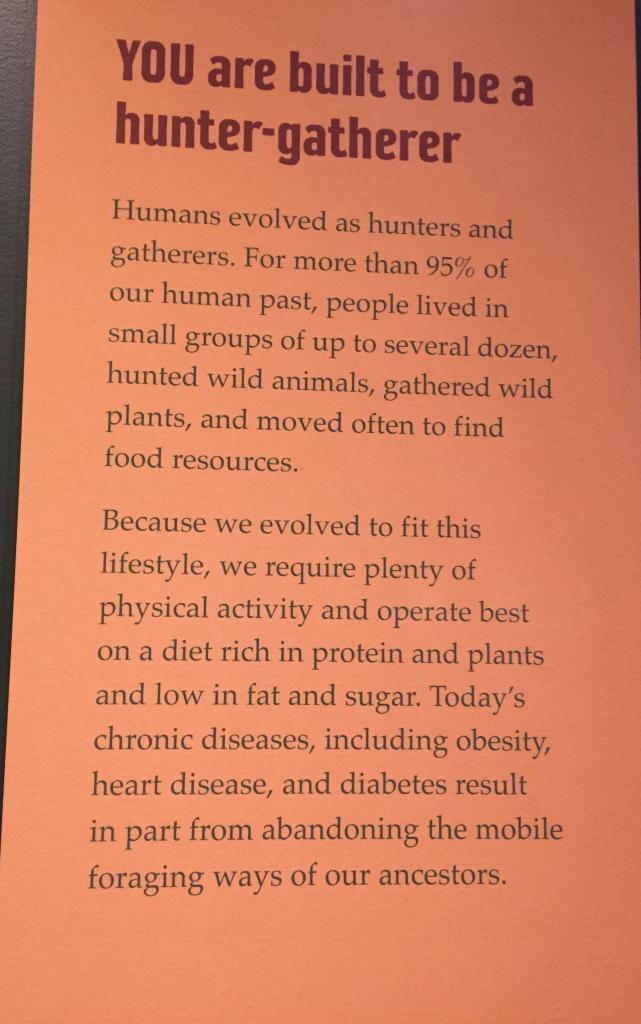

And this is another one: we should all still be hunters and gatherers.

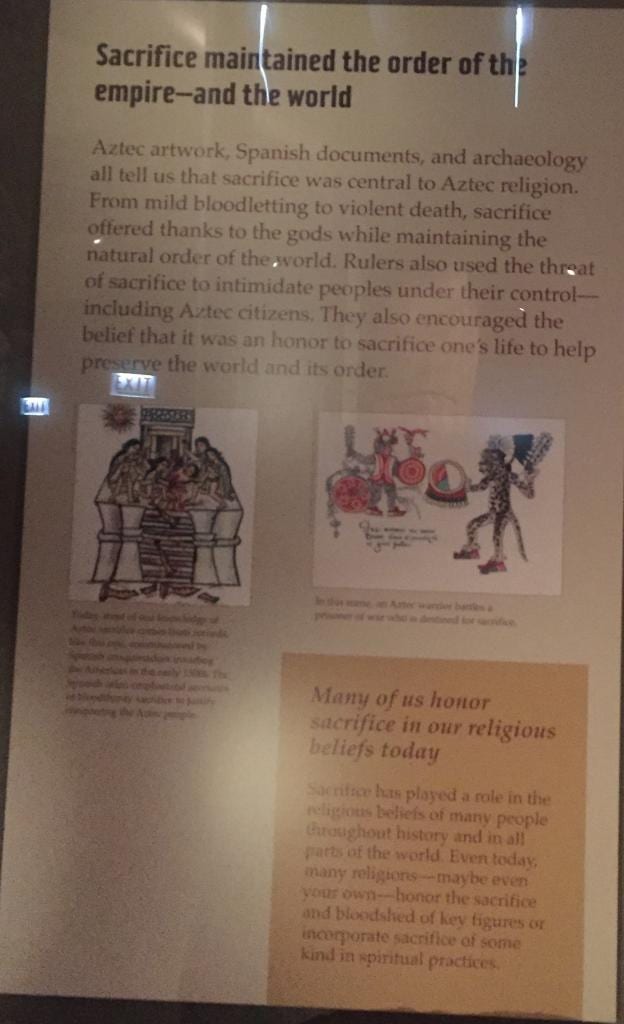

But here’s the third piece of text that had me SMDH:

The text?

Many of us honor sacrifice in our religious beliefs today.

Sacrifice has played a role in the religious beliefs of many people throughout history and in all parts of the world. Even today, many religions — maybe even your own — honor the sacrifice and bloodshed of key figures or incorporate sacrifice of some kind in spiritual practices.

Did the author of these sentences really fail to understand the difference between the belief that a religious figure undertook self-sacrifice or that believers should do so (Jesus, martyrs, the Lenten sacrifices of Christians), and the killing of prisoners in the name of appeasing the gods? Is it not generally understood that part of the reason that the Aztec Empire fell so easily to the Spaniards is that their treatment of their subjects, including the seizing of victims for sacrifice, meant that those subject peoples were willing to ally themselves with the Spaniards? Or was it simply deemed necessary to whitewash this aspect of the Aztec Empire, all the more because of the exhibits constant linking (via text and videos) of these ancient peoples to their modern day distant descendants (or perhaps not descendants at all, but simply people whose ancestors occupied similar territory, since, after all, we’re talking ancient history, that is, prior to the “tribal” structure with continuity to modern times).

I should also add that, in the same manner as the Africa exhibit ends with the slave trade, so, too, the Ancient Americas exhibit ends with a room that functions as a sort of memorial to the cultures ended and lives lost over the centuries after European contact. Maybe that will eventually be moved over to the non-Ancient exhibit, when that’s complete; maybe the intention really is for the two exhibits to have a divide of 1492, and for the new exhibit to tell a story very much with a lens of loss due to the Europeans.

And that’s when it really struck me: this whole narrative is incomplete. In each of the three exhibits, the Europeans are the outsiders who come in and upend everything (even though that narrative isn’t as stark, and more incidental in the case of the Pacific Islands). But nowhere is there any sort of exhibit in which the Europeans have any sort of culture other than that of conqueror and slaver. Heck, there are multiple explanations of how the Europeans ended up the more technologically advanced conquerors. There’s Jared Diamond’s explanation (it was all geography, both in terms of domesticatible animals/plants and the large land mass of Eurasia enabling technological exchange over time) and, dangit, it seems to me there was another book out not too long ago that basically said it was all cyclical and bad luck that the Chinese fell behind. Even if there’s a degree to which they’d need to put up disclaimers of “this is all one interpretation” wouldn’t that be worthwhile to explain? And wouldn’t it make sense to give the Europeans a culture, other than just swarming aliens?

So that’s my museum-ing for the time being. What do you think?