Some time ago, I wrote a blog post asking, “Is Megan McArdle a freeloader?“, referencing her because she’s told at least part of her (childless) life story in her recent(-ish) book and because there’s at least some degree of overlap between her (admittedly much more numerous) readers and mine. The answer to that rhetorical question was a somewhat lame, “no, not really.”

But this weekend’s Economist had a somewhat different take on the issue. The childless, they say, are not freeloaders who spend all their free time having fun, but do actually contribute to the world — they contribute more to charity upon their deaths (though by a measly $10,000), are more likely to create charitable foundations (though the absolute number of foundation-creators has got to be small in total) and certain key politicians — e.g., 5 of the 7 G7 leaders — are childless.

But despite that push by many environmentalists for a shrinking population, the Economist takes the still-conventional wisdom approach that a society needs to reproduce its population in order to keep its economy healthy. How they reconcile their praise of the childless with this recognition of the need for a next generation is interesting:

But to sustain public pensions in the long term, countries do not actually need more parents. What they need instead is more babies. It is possible to combine a high rate of childlessness with a high birth rate, provided people who become parents have more than one or two children. That was the pattern in many Western countries a century ago. Ireland, yet another country with a childless leader, still manages it today.

In other words, The Economist’s suggested model, in light of a substantial portion of the population not having children, is for the rest of us to pick up the slack, or, alternatively, to not worry about the Duggar’s 19 kids, or the half-dozen or so kids in what counts as “large families” in my own neighborhood.

And in some ways this makes sense. After all, there are economies of scale in child-rearing. You have hand-me-downs, both clothes and toys, and the experience you gain with the first child, allows you to manage numbers two, three, or even four with greater ease. If this path, of a mix of childless and multi-child families, works out to a reasonably sustainable total fertility rate without individual couples being pushed into one direction or another, that’s great.

But is such a demographic outcome sustainable, if it goes too far, if the proportion of childless individuals becomes too great? I mean, sure, you can get the numbers to work in a number of ways. Half the population can be childless, and half can have an average of 4 children apiece, and half of those children would, in turn, chose to reproduce and half not. But this would produce, and at the same time presumably cause a significant cultural splintering.

The key question is whether, if present trends continue in the long term, the Economist’s rosy assessment of “childless people spend their time and money helping society, so it’s all good” will be true (to the degree that it’s even true at the moment, instead of only being true for a minority), or whether, instead, the snide comments about “breeders” and the attitude underlying them (as well as the new philosophy that parents bear the moral responsibility for their descendants’ carbon emissions, up to infinity) will provoke conflicts between parents and nonparents on such issues as how much money the government should spend on programs benefiting children. But, hey, as long as the rates of the childless are well below a majority, the rest of us can outvote them, right?

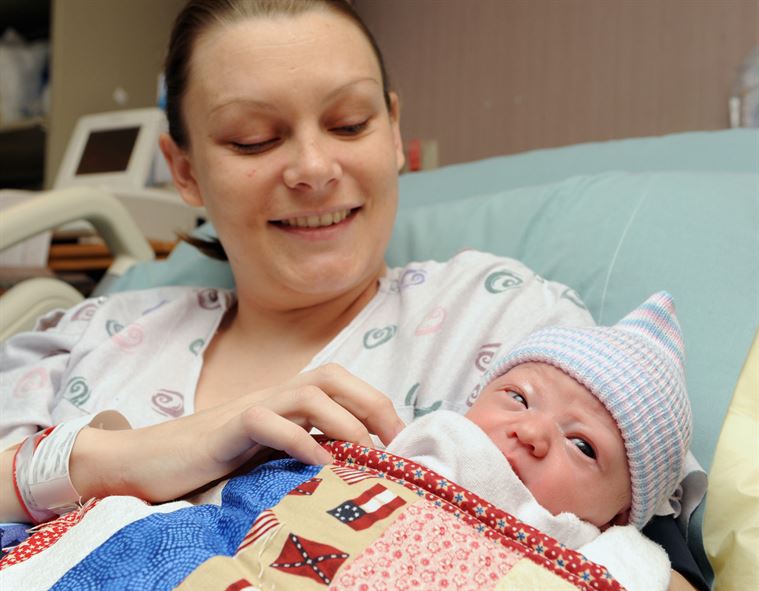

Image: http://www.mountainhome.af.mil/News/Photos/igphoto/2000602500/ (public domain; US gov’t photograph)