First of all, I’d like to share a bit of a Megan McArdle article from the other day, “As a Woman in Tech, I Realized: These Are Not My People.” After describing an early career as a technology consultant, and her subsequent departure for, eventually, journalism, she writes

No, the reason I left is that I came into work one Monday morning and joined the guys at our work table, and one of them said “What did you do this weekend?”

I was in the throes of a brief, doomed romance. I had attended a concert that Saturday night. I answered the question with an account of both. The guys stared blankly. Then silence. Then one of them said: “I built a fiber-channel network in my basement,” and our co-workers fell all over themselves asking him to describe every step in loving detail.

At that moment I realized that fundamentally, these are not my people. I liked the work. But I was never going to like it enough to blow a weekend doing more of it for free. Which meant that I was never going to be as good at that job as the guys around me.

Second, a statistic from my twitter feed, linking to an article at the World Economic Forum:

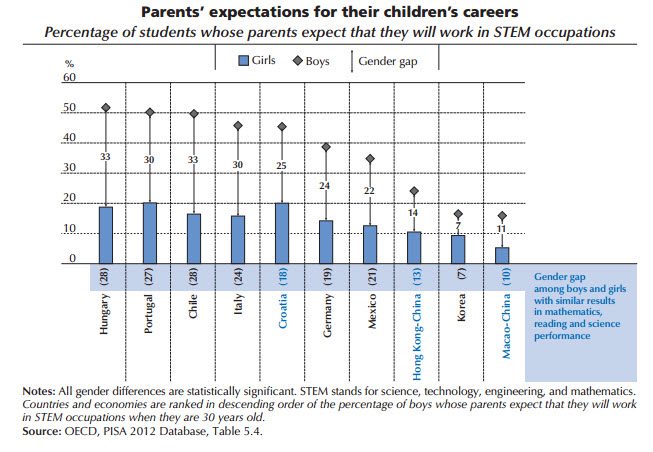

Parental influence is also a factor. An OECD report found parents are “much more likely to expect their sons to work in STEM careers than daughters, even if they show the same ability”. The report found 50% of parents in Chile, Hungary and Portugal expect their sons to work in STEM fields, but less than 20% expect the same of their daughters.

This comes from a report analyzing PISA data (very rich with data); here’s the full table (from page 140) – why only these selected countries are included isn’t clear to me:

Now, I know there are a lot of issues surrounding these questions. Are girls discouraged from studying math and science? Are boys given more support in their out-of-school science-related hobbies? Are women discriminated against in entering tech fields or harassed once they enter the field? etc.

But consider this: why is there such a push for women to go into STEM fields? Partly, yes, there are nice thoughts about the great contributions women can make, but there’s also an assumption that this needs to happen for purposes of gender equity, because these fields are highly-paid. After all, men also make up a disproportionate number of trash collectors and this doesn’t cause any anxiety from anyone.

But at the same time, those careers may be high-paid, but they’re not particularly high-status, by which I mean that the individuals working in those fields don’t have a lot of social prestige. They’re stereotyped as nerds, and largely because the stereotype tends to be true. When we repeat the “do what you love” mantra, we don’t have in mind crunching numbers or coding. When parents encourage their sons to go into STEM fields more frequently than their daughters, isn’t it possible that part of the reason is the perception that boys are disproportionately likely to be weak in social skills, so be considered ill-suited for other types of work, relative to girls? A girl, on the other hand, why, “she can do anything,” and pursue her dreams, so why not dream of something better than sitting at a computer writing code?

But now, rather than conceding certain occupations as a refuge for nerds, we’ve upped our demand that all occupations belong to those strong in social skills, and that the nerds have no place in society. In yet another variant of Boys Are Bad and Girls Are Good, we now need girls in computer science and engineering because their superior social skills and care for the environment and for others will Make The World A Better Place, and, indeed, the way to persuade them to enter these fields is by marketing them was Ways To Make The World Better.

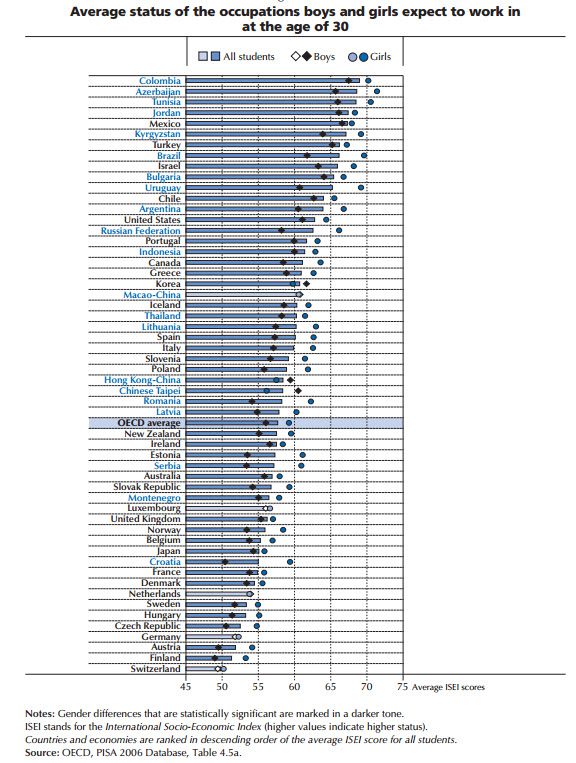

But here’s one final data point: STEM careers are only a small portion of the working world, and career ambitions cover a much wider of fields. Here’s the OECD graph plotting boys’ and girls’ career ambitions by status, according to a standardized framework:

The overall low scores of places like Germany and Switzerland are explained in the study as due to the apprenticeship and tracking systems of those countries:

Figure 4.7 shows that in countries where students are sorted into separate tracks before they are 15 years old, students hold particularly low expectations for their future occupations. This may be because those who are already in education tracks that do not lead to professional and managerial jobs tend to adjust their expectations accordingly and align their expectations to fit what is expected of them (Buchmann and Park, 2009). In contrast, students in more open, comprehensive systems can nurture hopes to be employed in jobs that require high skills, even if they have no real chance of attaining their goals. Students who hold high expectations may be more motivated and ready to put time and effort into their studies because they can see purpose and meaning in their pursuit of excellence.

But of the sex differences, the report offers no explanation, only a description:

across almost all countries and economies that participated in PISA 2006, girls held more ambitious career expectations than boys. On average across OECD countries, girls were 11 percentage points more likely than boys to expect to work as legislators, senior officials, managers and professionals. France, Germany and Japan were the only OECD countries where similar proportions of boys and girls aspired to these occupations, while in Switzerland and the partner economies Hong Kong-China and Chinese Taipei, boys generally held slightly more ambitious expectations than girls. The gender gap in career expectations was particularly wide in Greece, Poland and the partner countries Azerbaijan, Brazil, Croatia, Romania, Serbia and Uruguay. In all of these countries, the proportion of girls who expected to work as legislators, senior officials, managers or professionals was 20 percentage points larger than the proportion of boys who expected to work in those occupations (ISCO88 groups 1 and 2).

So that’s my vague and ill-defined gripe/set of observations for the day.

Image: Erlenmeyer Laboratory Chemistry Science Flasks, from http://maxpixel.freegreatpicture.com/Erlenmeyer-Laboratory-Chemistry-Science-Flasks-606611