As many a Catholic site repeats in the wake of Bernie Sanders’ rising political fortunes, the Church rejects socialism in its vainglorious quest to abolish private property and demolish all difference. One need only look to Rerum Novarum:

The socialists, therefore, in setting aside the parent and setting up a State supervision, act against natural justice, and destroy the structure of the home. […]

And in addition to injustice, it is only too evident what an upset and disturbance there would be in all classes, and to how intolerable and hateful a slavery citizens would be subjected. The door would be thrown open to envy, to mutual invective, and to discord; the sources of wealth themselves would run dry, for no one would have any interest in exerting his talents or his industry; and that ideal equality about which they entertain pleasant dreams would be in reality the levelling down of all to a like condition of misery and degradation. Hence, it is clear that the main tenet of socialism, community of goods, must be utterly rejected, since it only injures those whom it would seem meant to benefit, is directly contrary to the natural rights of mankind, and would introduce confusion and disorder into the commonweal. The first and most fundamental principle, therefore, if one would undertake to alleviate the condition of the masses, must be the inviolability of private property. This being established, we proceed to show where the remedy sought for must be found.

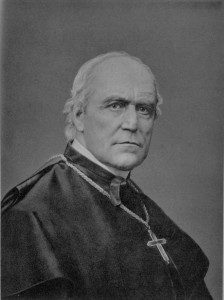

The issue is, alas, not so simple. Socialism, while in certain forms undeniably anathematized by the Church, actually had a profound influence on the development of modern Catholic Social Teaching, especially as laid out in the encyclical cited above. As many an American liberal (in the classical sense) might suspect, the culprit is (God help us), a German: Friedrich Emmanuel Freiherr von Ketteler, Bishop of Mainz.

The cleric led a complicated and very interesting life (additional sources here and here with some of his collected writings here), but what interests me in this piece is his dalliance with Lassallian Socialism, a particularly state-enamored form of socialist thought, so much so that Marx detested it (because, as a responsible reader of Marx is aware, Marx was no fan of the state). Witness New Advent on von Ketteler and emerging German social movements:

In 1848 he believed that social reform had to begin with the interior regeneration of the soul [here we might read “begin with the formation of conscience”]. Later he was to enter more deeply into economical problems. When about 1863, the Liberal Schulze-Delitzsch and the Socialist Lassalle made forcible appeals to the German workingmen, Ketteler studied their doctrines and even consulted Lassalle in an anonymous letter on a scheme of founding five small co-operative associations of workingmen.

In opposition to Schulze-Delitzsch he pointed out the futility of the remedies proposed by the Liberals; he advocated labour associations, and even accepted the idea of co-operative unions to be established, not as Lassalle wished, by state subvention, but by generous aid from Christian capitalists. In a Socialistic meeting at Rondsdorf, 23 May, 1864, Lassalle paid homage to Ketteler’s book. On his side, Ketteler, whom three Catholic workmen had asked in 1866 if they could conscientiously join the “workingmen’s association” founded by Lassalle, was disposed to dissuade them from so doing owing to the anti-religious spirit of Lassalle’s successors; nevertheless in his reply he duly acknowledged Lassalle’s “respectful recognition of the depth and truth of Christianity.” At this time he counted particularly upon the initiative of Christian charity for the organization of productive co-operative associations destined to restore social justice on a more equal scale. In 1869 he went still further: in a sermon preached near Offenbach, 25 July of that year, he particularized certain urgent reforms (increase of wages, shorter hours of labour, prohibition of child-labour in factories, prohibition of women’s and young girls’ labour); these claims, he thought, should be presented to the public authorities. In Sept., 1869, at the Fulda conference of the German bishops, he showed how necessary for the removal of economic evils was the intervention of the Church in the name of faith, morals, and charity. He also made clear the right of workingmen to legal protection and urged that in every diocese some priests should be selected to make a study of economic questions.

While fiercely pro-conscience formation, seeing it as the root of all social change, von Ketteler refused to deny the efficacy of social action, demanding that workers receive protection from individual greed; to be frank and to use an anachronism, the bishop sounds like something of a Christian democratic socialist (and I needn’t mention Pope Benedict’s comments on the subject). He led the first Corpus Christi procession through Berlin since the Reformation; he championed the freedom of the Church (and in a very diplomatic tone!) against an encroaching German state, and, yes, he had a major influence on Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum. In other words, an anti-statist, socialist-influenced, German aristocrat, who opposed the formalization of Papal Infallibility stands at the heart of a seminal 19th-century century expression of Catholic Social Teaching.

What can we learn from this? For one, we might see that Catholicism is a complicated nexus of 24 distinct Churches, not a monolith held together by one tongue and one liturgy, but actually a diverse set of traditions and expressions held together by a common and true faith (in short, we shouldn’t make simple statements about the Church and its “clear” history). We might also question our assumptions about socialism. While I can’t lay out every reason here (a grad student does need to do his homework!), Catholicism and socialism enjoy a rich and complex relationship (one might even say that Chesterton’s quip, and I’m paraphrasing here, about there being “not too many capitalists, but too few” sounds an awful lot like Marx’ position on the workers’ owning the means of production). To act as if American liberal politics ought to be the baseline for the American Catholic is to ignore huge sections of Catholic teaching. Witness, once more, Rerum Novarum:

If we turn not to things external and material, the first thing of all to secure is to save unfortunate working people from the cruelty of men of greed, who use human beings as mere instruments for money-making. It is neither just nor human so to grind men down with excessive labor as to stupefy their minds and wear out their bodies. Man’s powers, like his general nature, are limited, and beyond these limits he cannot go. His strength is developed and increased by use and exercise, but only on condition of due intermission and proper rest.

In short, being Catholic is complicated. The formation of conscience has long been the core of Catholic teaching in the moral realm (and this undergirds the economic, no?), regardless of what certain contemporary detractors say. Easy binaries and simple formulations must go if we desire to live by the difficult demands of the Gospel, which ask us to reach beyond ourselves, to pour ourselves out for the love of one another. And while the full network of roots beneath Catholic Social Teaching is not socialist per se, such theories have their place among its influences. I’ll leave you with Rerum Novarum:

“It is lawful,” says St. Thomas Aquinas, “for a man to hold private property; and it is also necessary for the carrying on of human existence.”” But if the question be asked: How must one’s possessions be used? – the Church replies without hesitation in the words of the same holy Doctor: “Man should not consider his material possessions as his own, but as common to all, so as to share them without hesitation when others are in need. Whence the Apostle with, ‘Command the rich of this world…to offer with no stint, to apportion largely.’”